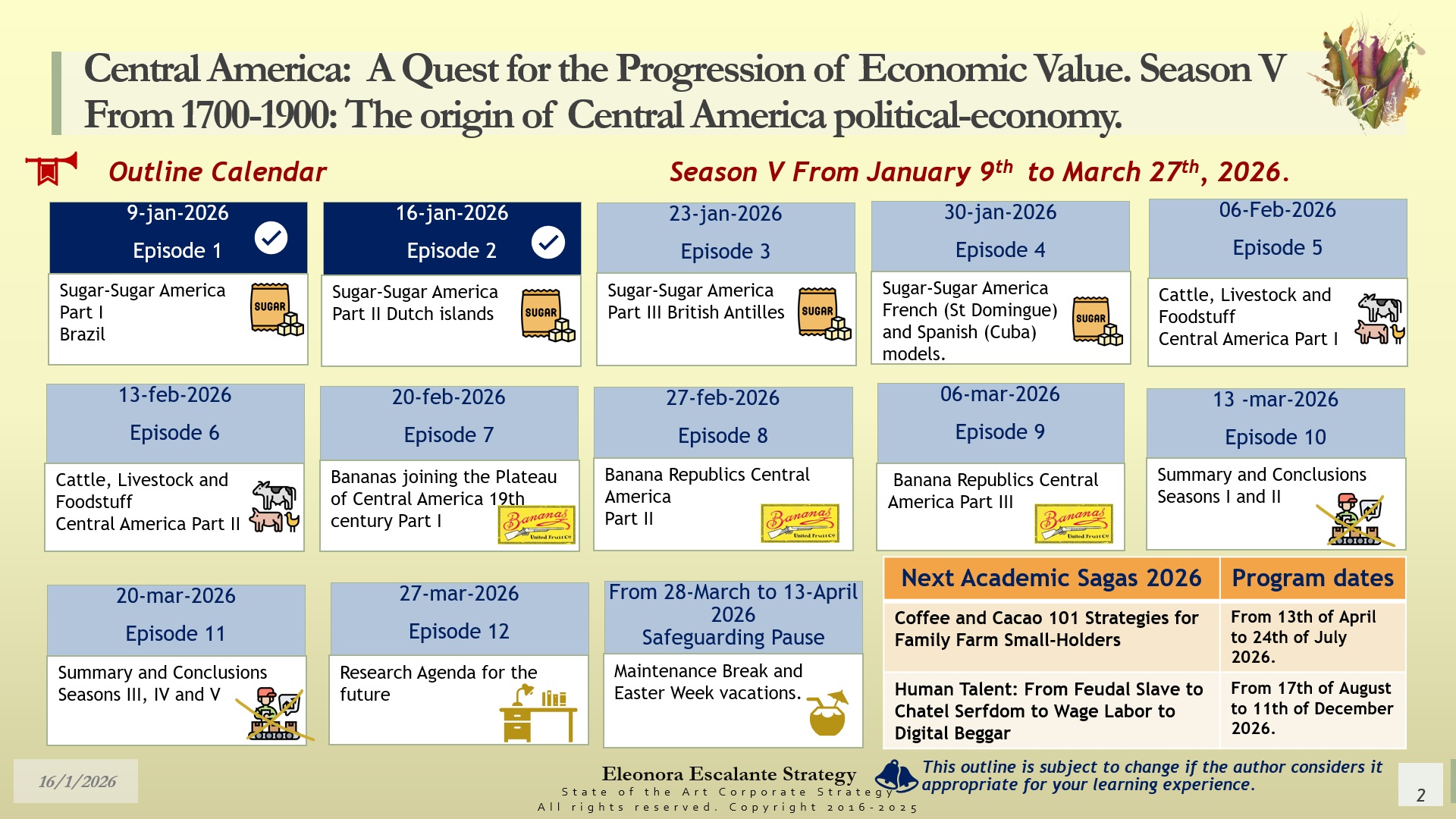

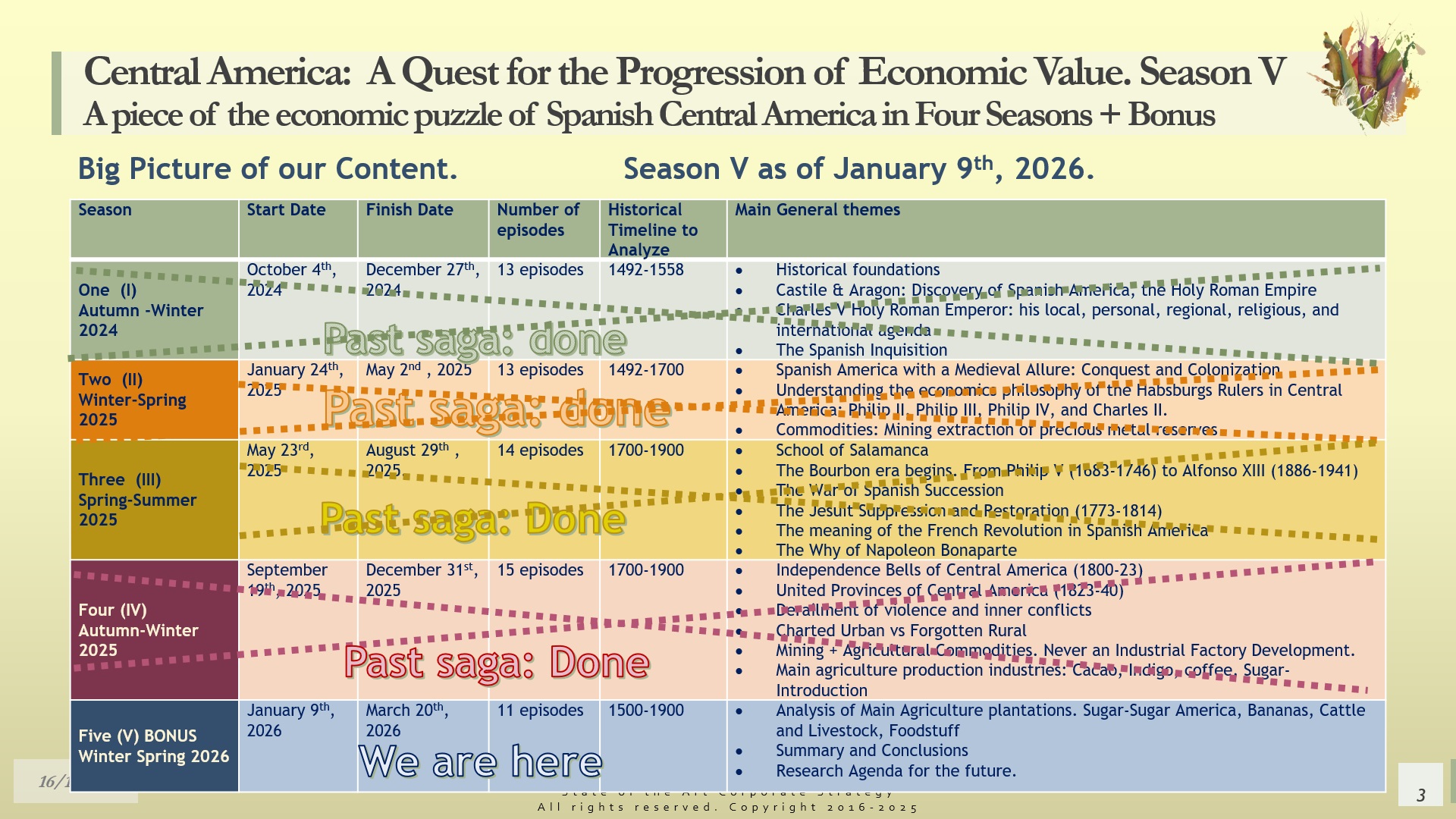

Central America: A Quest for the Progression of Economic Value. Bonus-Season V. Episode 2. Sugar Sugar America Part 2. The Dutch sugar

Dear Readers:

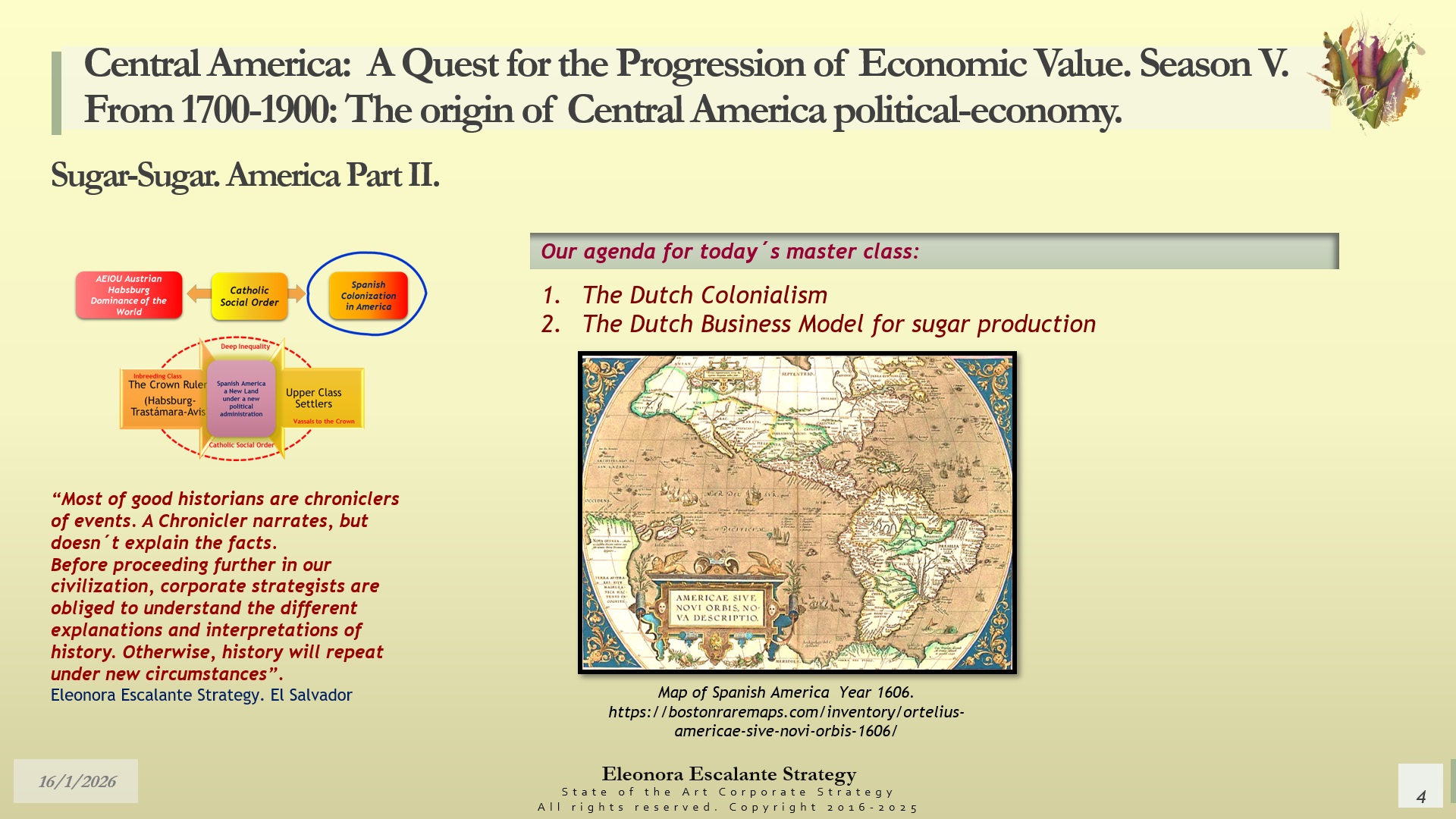

Our masterclass today is about the understanding of why the Sugar industry was shaped globally by the commercial interests of all the European Nations involved in the discovery of the riches of America. The Dutch were also part of this global trade of opportunities, and sugar represented a core business for this nation that succeeded in winning its independence from Spain in 1648.

We have analyzed two main themes:

1. The Dutch Colonialism, and its context

2. The Dutch Business Model for Sugar Production

During the weekend, feel free to pass the following package of slides material. Share it with your friends, colleagues, supervisors, and any member of your family who wishes to learn about how the political economy of Spanish America (and the Antilles) was established. Sugar plays an essential role in this process. We always recommend our readers to download this material, print it, and write questions and doubts on paper. At the end of your reading, on slides 16 and 17, you will find additional bibliography that may guide you to dig deeper into our class, previous to our strategic reflections, which always appear on Mondays.

We kindly request that you return next Monday, January 19, 2026, to review our additional strategic reflections on this chapter.

We encourage our readers to familiarize themselves with our Friday master class by reviewing the slides over the weekend. We expect you to create ideas that may or may not be strategic reflections. Every Monday, we upload our strategic inferences below. These will appear in the next paragraph. Only then will you be able to compare your own reflections with our introspection.

Additional strategic reflections on this episode. These will appear in the section below on Monday, January 19, 2026.

Strategic Reflections on “Central America: A quest for the progression of economic value. Bonus Season V. Episode 2. Sugar-Sugar America 2. The Dutch Sugar Business Model of Suriname.”

The contextual partnership between the Portuguese, Genoese, and the Dutch (15th century). Slides 5 and 6.

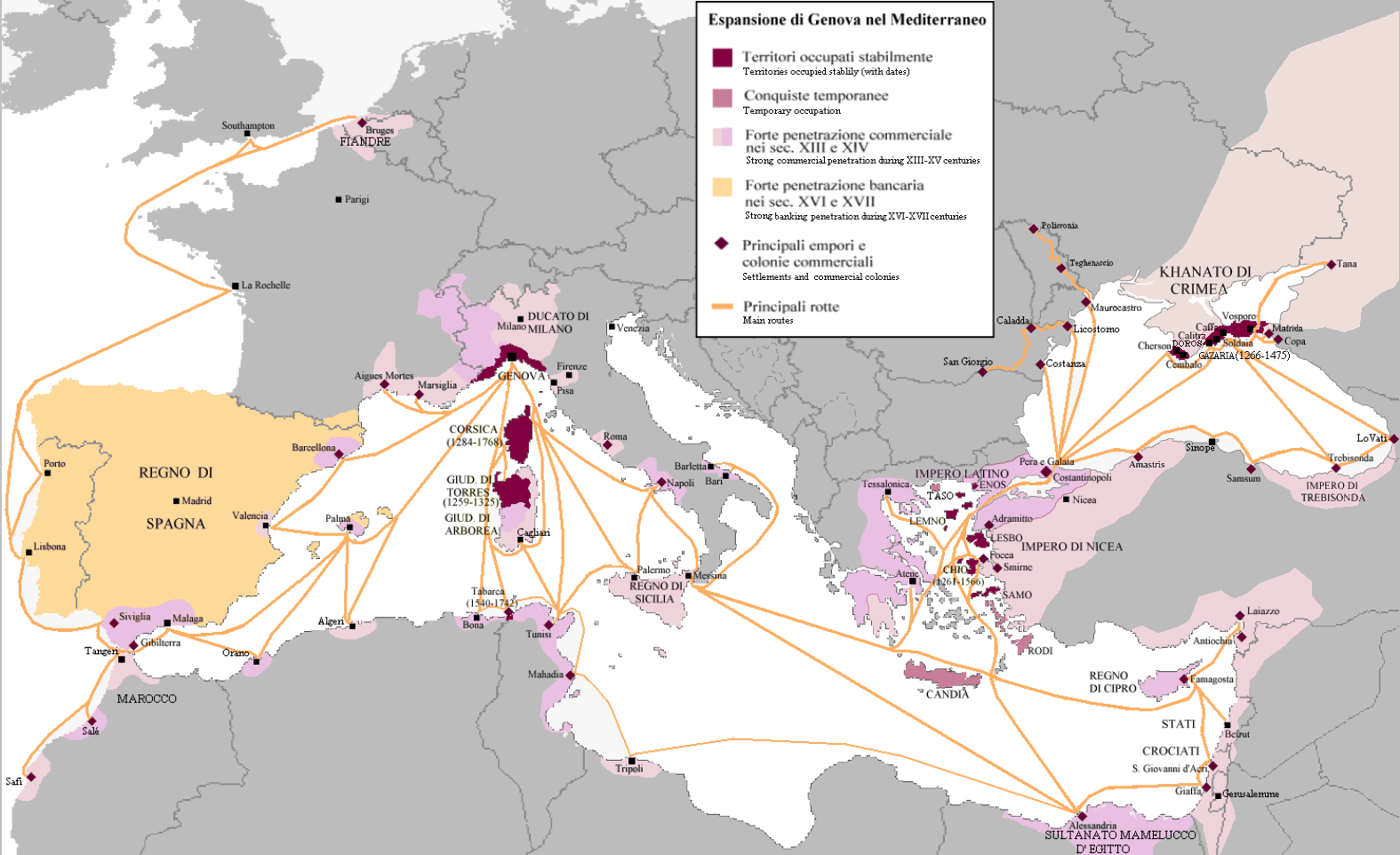

Even though official history has constrained us in our quest to understand the real causes of historical events, we have made an extra effort to comprehend how things unfolded from their original roots. The tripartite partnership of the kingdoms of Portugal, Genoa, and the Dutch is inferred through a unique commercial alliance called sugar production. Until the 15th century, sugar was imported from Asia and the Middle East, and the Mediterranean production of Sicily and other Mediterranean islands was being financed, marketed, and distributed by the Venetians and Genoese, who served specific luxury niches all over the royal houses of Europe and their respective aristocratic groups. When the Portuguese tested the sugar plantation model in their Atlantic Islands, Christopher Columbus (A Genoese) took the sugar plants to the New World, and from that point on, we have been investigating the way the business model was developed by each of the main empires targeting America. The tripartite alliance between the Portuguese, the Genoese, and the Dutch was pre-established before the discovery of the New World. There was a dynastic pre-established royal relationship between the Habsburg-Aviz (Austria-Portugal), the Valois-Bourbon (of Burgundy-Flanders territories), and the Castile-Aragón (Spain). But the expansion of the Genoese Republic was extraordinarily vast. The Genoese territories (in burgundy color map below), and their commercial extension flows take us beyond Corsica and all the Ottoman territories (former Byzantine), Alexandria (Egypt), the Levant, and as far as the khanate of Crimea. The presence of Christopher Columbus planting sugar in the island of Española is not a coincidence. It is not a symbol either. It was a perfectly profitable strategy that was planned beforehand. At the time of Columbus, Genoa was developing a consortium of a direct observatory to America, that involved aristocratic Genoese families, such as Balbi, Doria, Grimaldi, Pallavicini, Serra, and the descendants of the house of Visconti, all together with the Sforza descendants. According to historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto, the Genoese developed and established unique practices in the Mediterranean (such as chattel slavery) through crop plantations, and their financing was crucial in the exploration and exploitation of the New World. The role of Flanders (Territories of Mary of Burgundy, married to the Austrian Portuguese emperor Maximilian HRE) was impressive in the financing and refining of sugar production. Most of the refining business of the Mediterranean sugar production was transferred to the Dutch Lands, because they distributed sugar to the Baltic nations, prior to the conquest of America. Additionally, the financial sophistication of the Low Countries in places such as Brugge was beyond any comparison then.

The Dutch Colonialism. Slides 7 to 9.

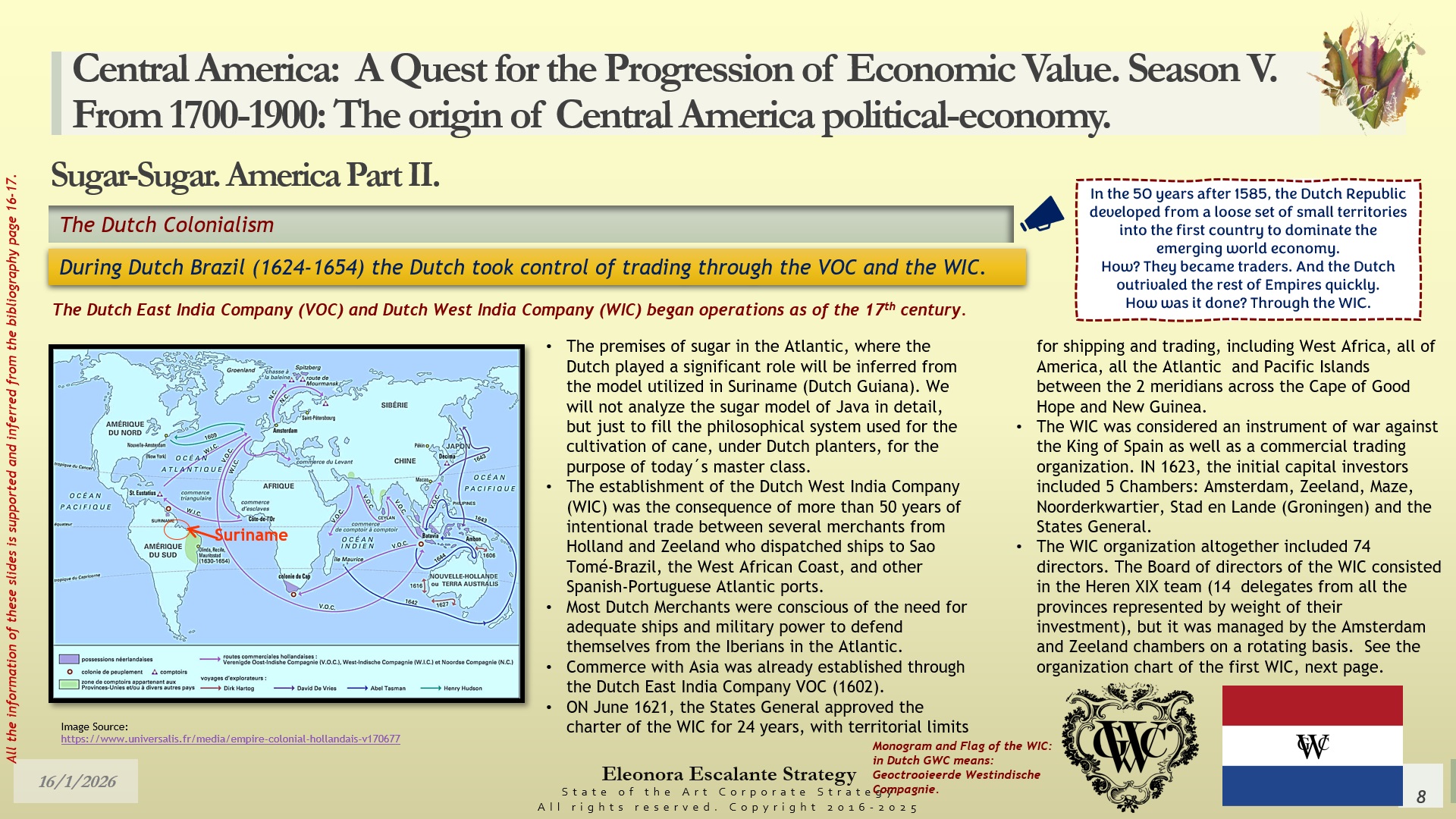

The Dutch imperialism was always focused on 2 activities: (a) trading (intermediation: buying cheap from producers all over the world and selling at a higher mark-up), and (b) financing using the most sophisticated instruments of its epoch, for public and private production projects, including shipping activities. The Dutch became intertwined with Portugal and Spain to establish trading posts in all their imperial domains, but primarily this network of commercial posts was established with Portugal along the western coastlines. The Dutch were strong in their corporate strategy from the 16th to the 19th centuries. They were expanding trade through transaction posts all over the coastlines where the Portuguese were actively establishing factories (centers of production of goods). The conflict of the Dutch Republic with Habsburg Spain (the Eighty years war) has been explained to us as a religious conflict. However, it is beyond that. We can observe that Spain was trying to stop the Dutch intrusion wave in America. Any war or geopolitical conflict stops investments and economic development. The Dutch were stopped from acting in Spanish America by a European religious war, at least during the 16th century. Are you aware of this?

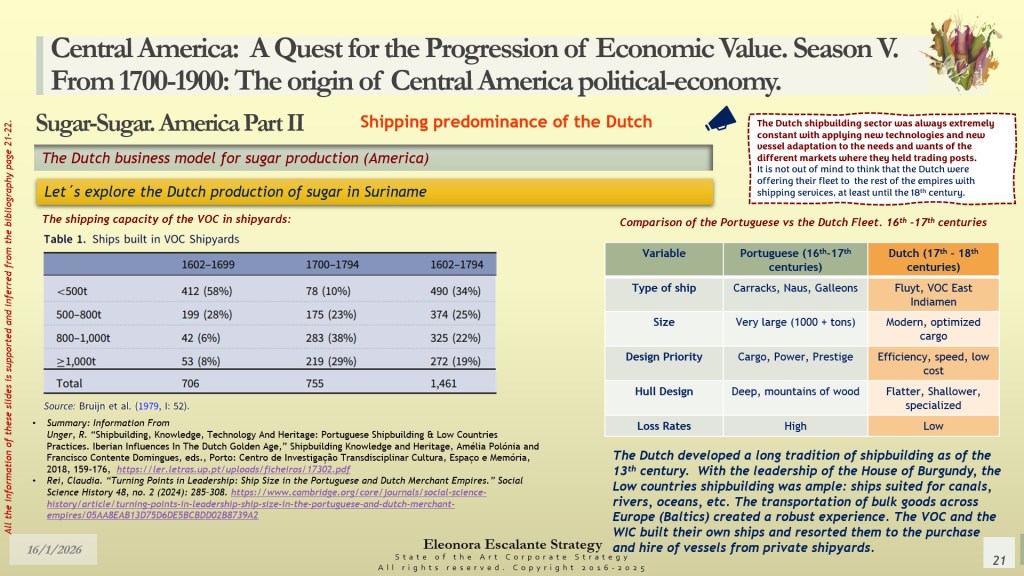

Nonetheless, the Dutch sugar interests were so traditionally substantial because they facilitated the last part of the value chain (the refining and distribution one). The Dutch continued to establish themselves in several parts of America. We have extrapolated that the Dutch fleet was serving the Portuguese in their shipping role for pulling out the muscovado sugar from Brazil to Antwerp, and later to Amsterdam. Dutch ships loaded sugar from Brazil to the Northern Part of the Dutch Republic, where they moved after 1585.

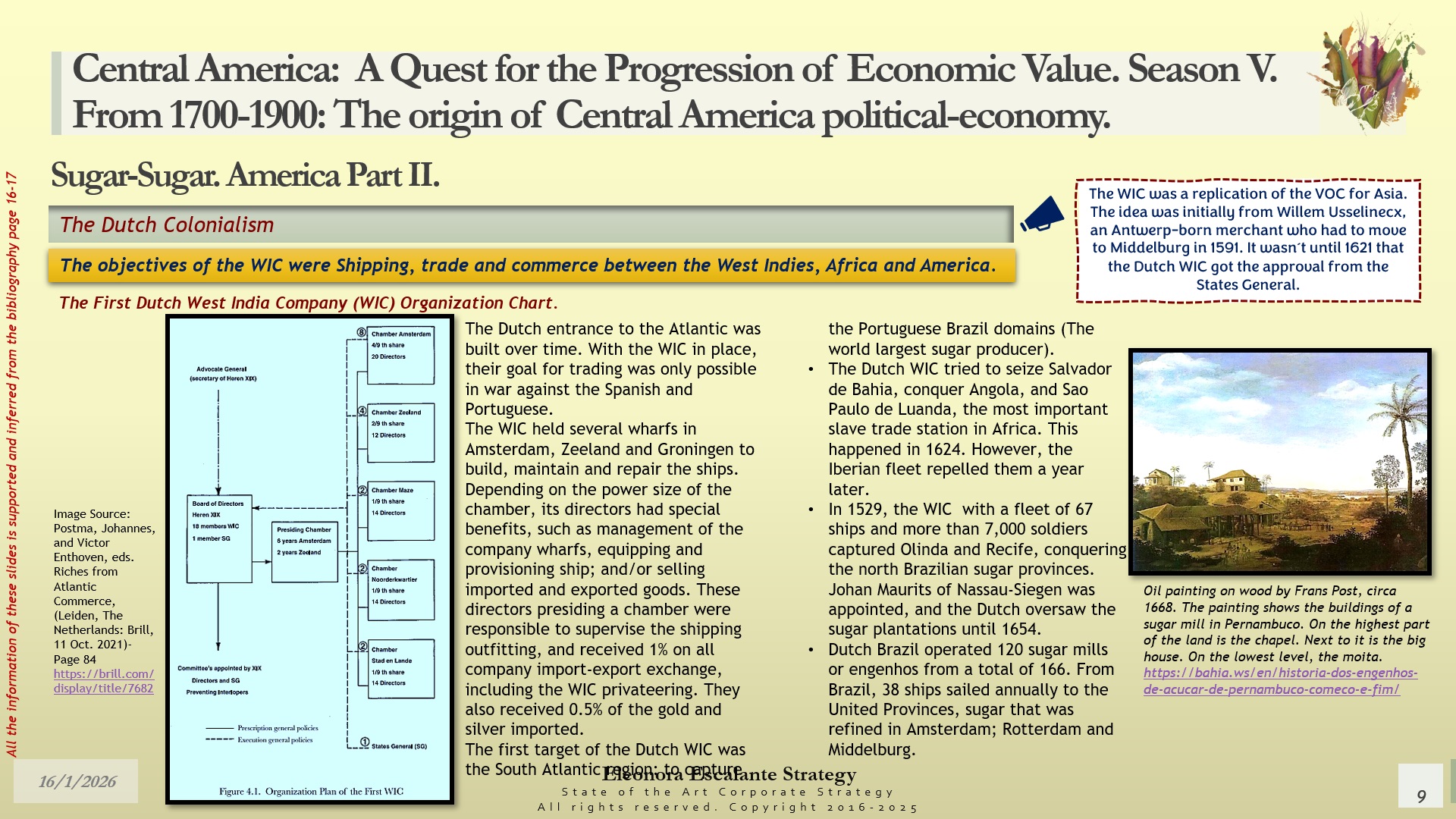

As of the beginning of the 17th century, the Dutch played a higher role, by introducing a huge control of trading through a private-public partnership figure: The Dutch East Indies Company (VOC in Dutch) for Asia; and the Dutch West Indies Company (GWC in Dutch or WIC in English). Both private-public corporations were established in 1602 and 1621, respectively. Slide 9 is our summary of how the WIC was formed with its original organization. The first Dutch West India Company organization chart is explained in slide 9. The importance of the WIC relates to its role as investors to the Dutch business of sugar in the Atlantic World. WIC was the milieu for supplying slaves for sugar production in America and beyond that. The period of Dutch Brazil was analyzed last Friday (From 1624 to 1654).

Our acumen has established two new hypotheses beyond the official purpose of the Dutch trading corporations. Both companies were established with specific territorial limits. The VOC was established for the Portuguese domains as of the Treaty of Tordesillas, and the WIC was established for the Spanish domains. However, as of the Fall of Antwerp (1585), both companies were instruments of war against the king of Spain (not Portugal) and as commercial trade ventures. The collaboration of the Dutch with Portugal was not interrupted, despite the period of conflict in Dutch Brazil. The first hypothesis leads us to extrapolate that the Dutch continued to provide shipping services to the Portuguese Brazil plantation needs and wants, and that includes a partial or most of the transportation of more than 6 million Africans (from 1501 to 1875) to wherever they were needed. Most historians believe that the Dutch played the official shipping role for all the empires, not just for their own needs. It is well possible to infer that the Dutch fleet was employed by the French, Portuguese, Spanish, and British, until the British took its superpower in its own shipping capacities as of the 19th century. The emergence of a new power in something meant the diminishing position of the former one. The second hypothesis is about the value of slavery beyond operational costs for plantations. Through our study of today, we have discovered that slaves were considered an appreciated source of collateral for obtaining credit in European Banking houses. This is a remarkable breakthrough, because slavery was not only used for operational field hand labor or for adjacent activities of the colonial empires. Slaves were also an asset that helped to increase the value of debt acquired for the operations of sugar mills. Read slide 9.

The Dutch Business Model for sugar production (America only): Slides 10 to 20.

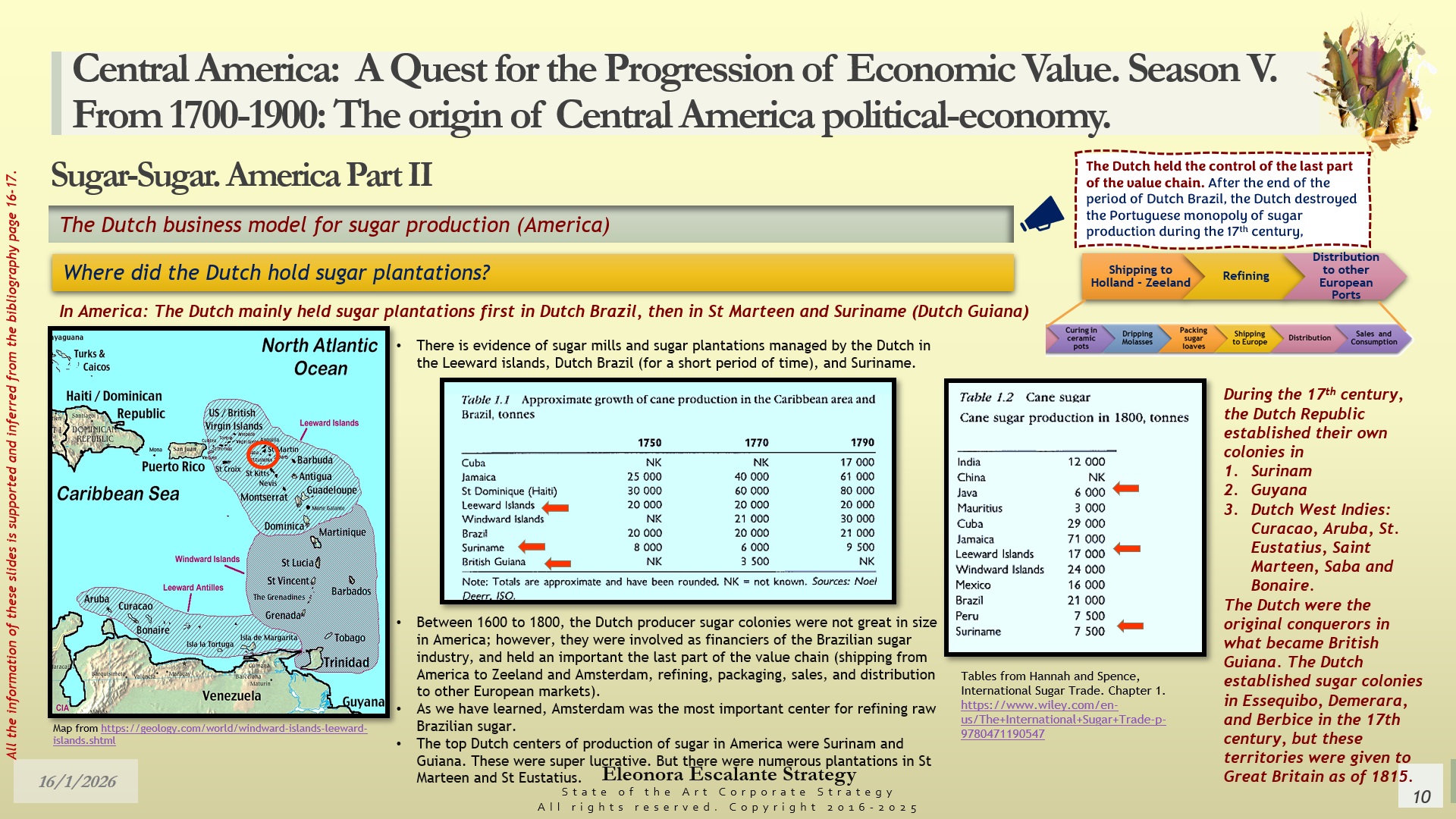

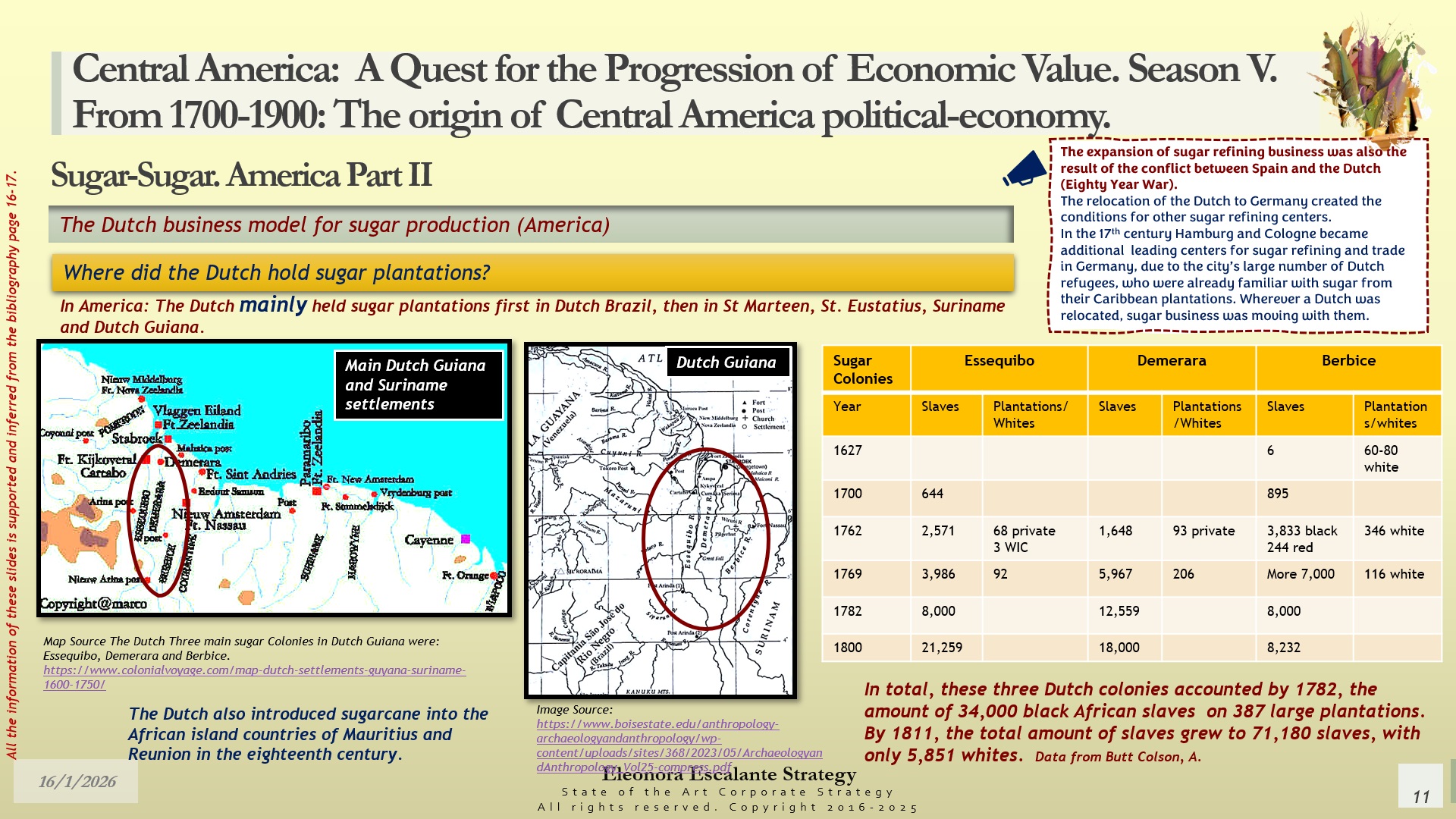

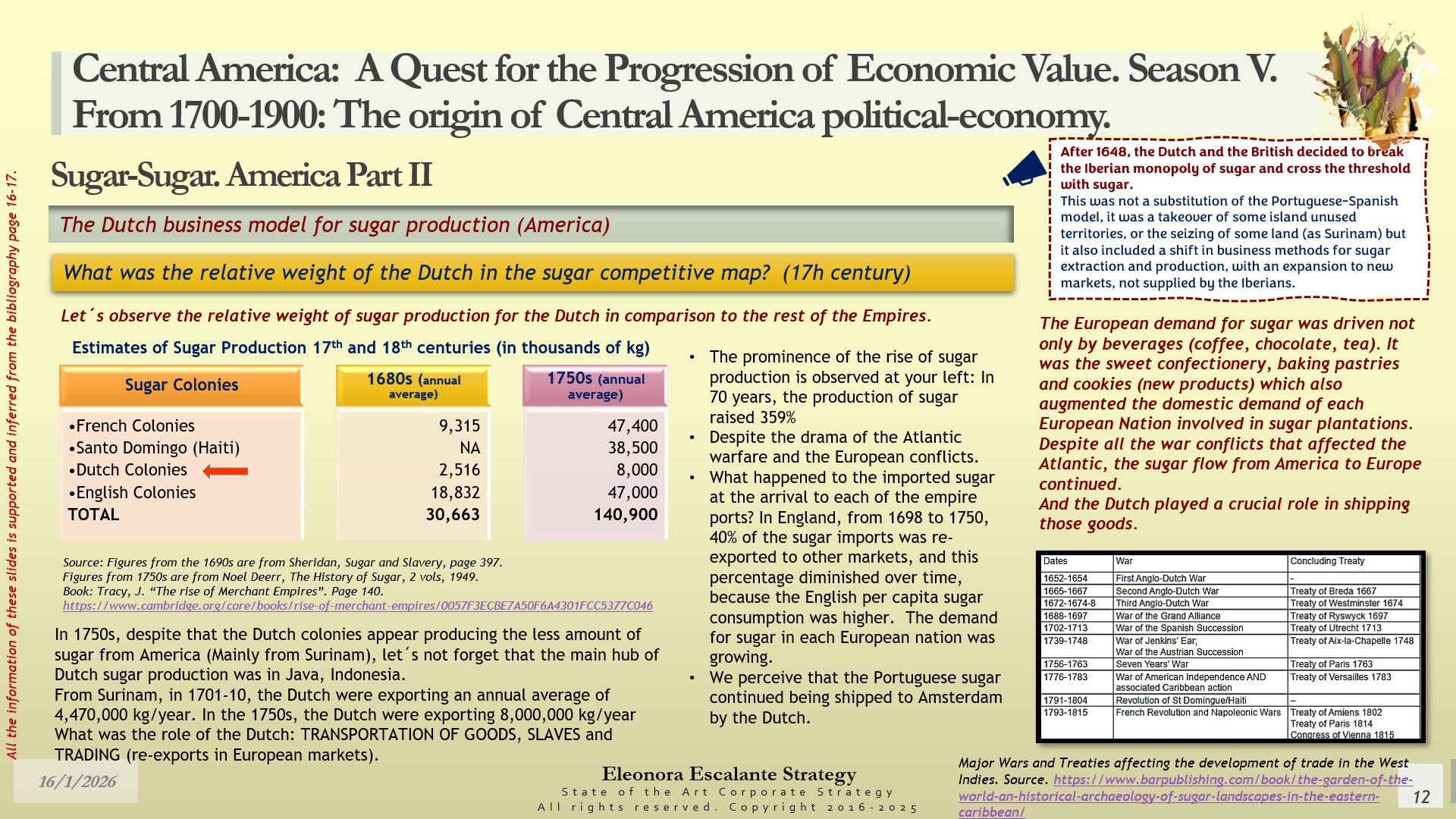

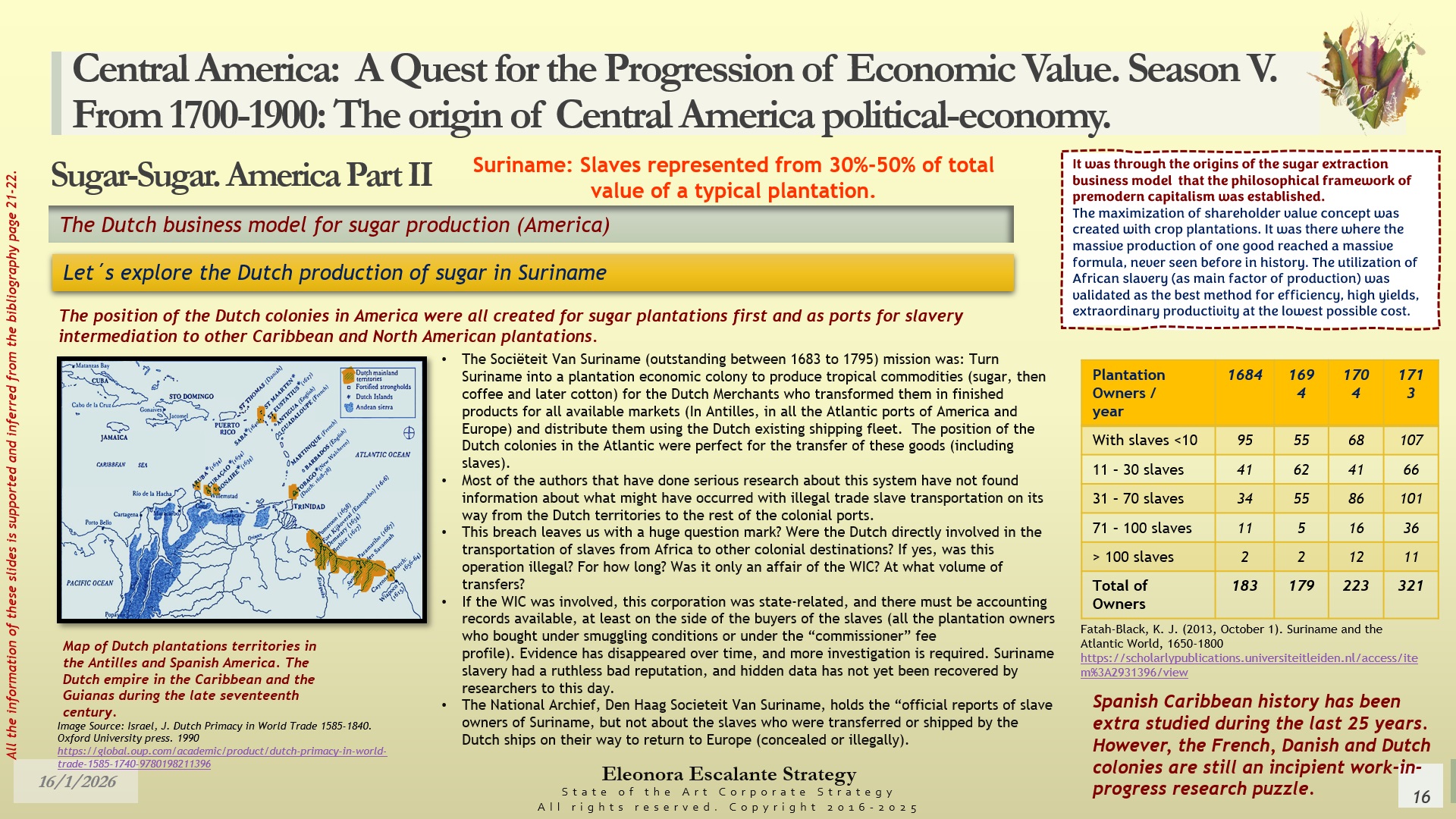

After showing you the territorial composition of the Dutch colonies in America (slide 10), we have appreciated that the start timing for sugar production was during the Dutch Brazil period, and later with Dutch Guiana, where they established the sugar colonies in Essequibo, Demerara, and Berbice. The Suriname colony was established in 1667. The Dutch held control of the Dutch West Indies islands: Curacao, Aruba, St Eustatius, Saint Marteen, Saba, and Bonaire. Slides 10 and 11 show the geographical location of Dutch Atlantic sugarcane plantations. Slide 12 is a comparison of the weight of the Dutch Empire’s presence in sugar production, comparing it to the French and English Colonies. The numbers do not show an important relative weight of the Dutch in terms of percentage of thousands of kg/annual averages. For example, the Dutch Atlantic colonies produced 8% of the total Antilles production on yearly average of the 1680s, while in the 1750s, it barely reached 5.7% of the total production. See slide 12.

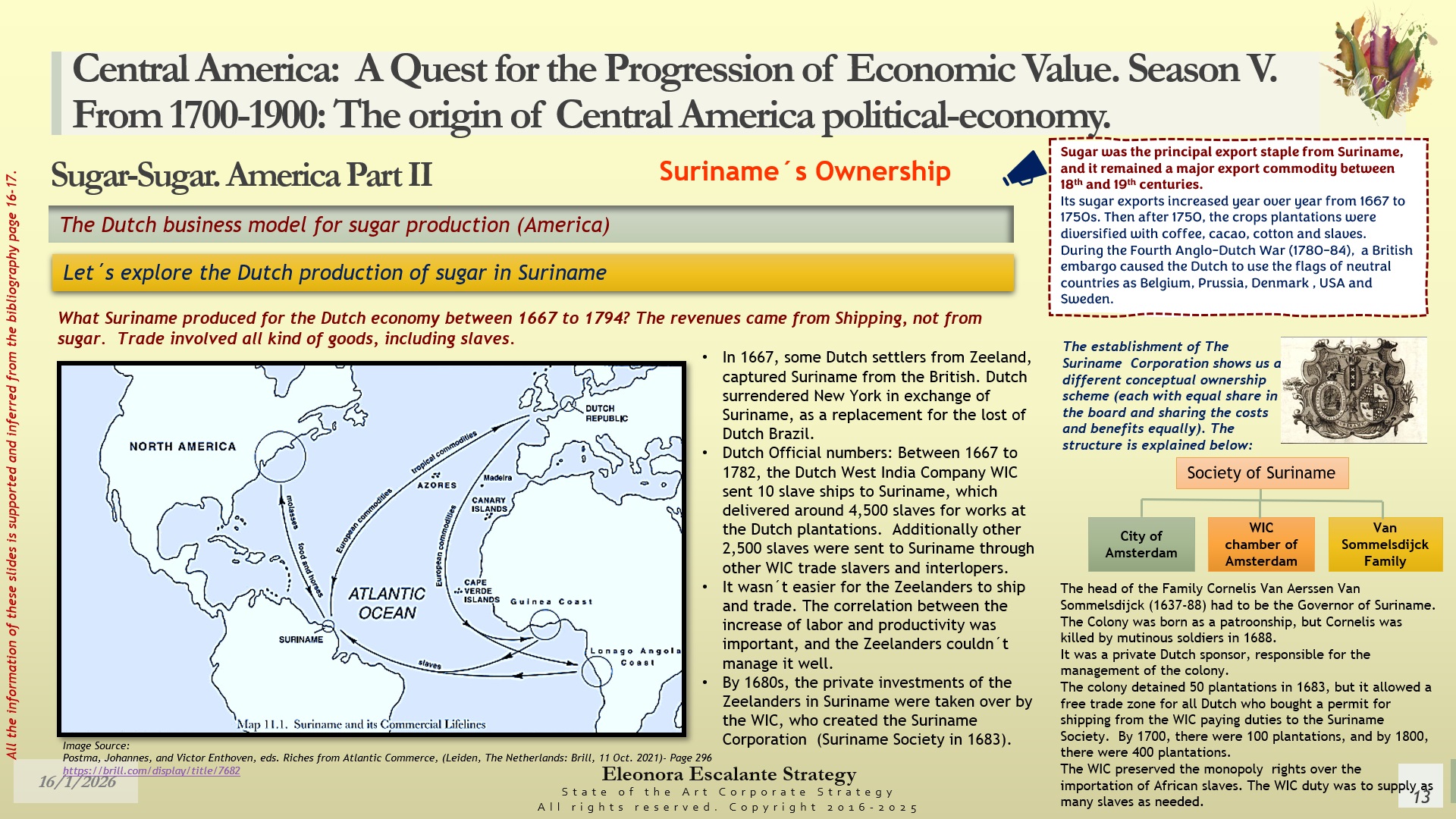

The colony of Suriname between 1667 and 1794 was so important for its bridge location to the Atlantic and North America, not because of sugar for the Dutch ports in Europe, but because Suriname might have meant a strategic hub for the distribution of slaves from Western Africa to the rest of the Antilles and North America (officially under the WIC until 1738, and later in the hands of private Dutch companies, which traveled with flags of other empires). We can’t take the risk to assert that the Dutch private corporations were the only direct intermediaries for slave trading from Africa (as MCC), or how many ships the Dutch provided to illegally transport the African slaves to other territories in the Atlantic. However, the experts on re-exports were also the Dutch. The New England ships carrying 30,000 horses to Suriname might have returned with slaves brought by the Dutch to Suriname from Africa, too. We have been searching for robust proof of evidence during our last week’s research, and we are limited to diagnosing the idea as a new hypothesis. On the other hand, we found plenty of information about the establishment of the Suriname corporation, which is described in slide 13. We decided to limit our publication to Suriname plantations, and not to Java-Indonesia, because our domain of research is America.

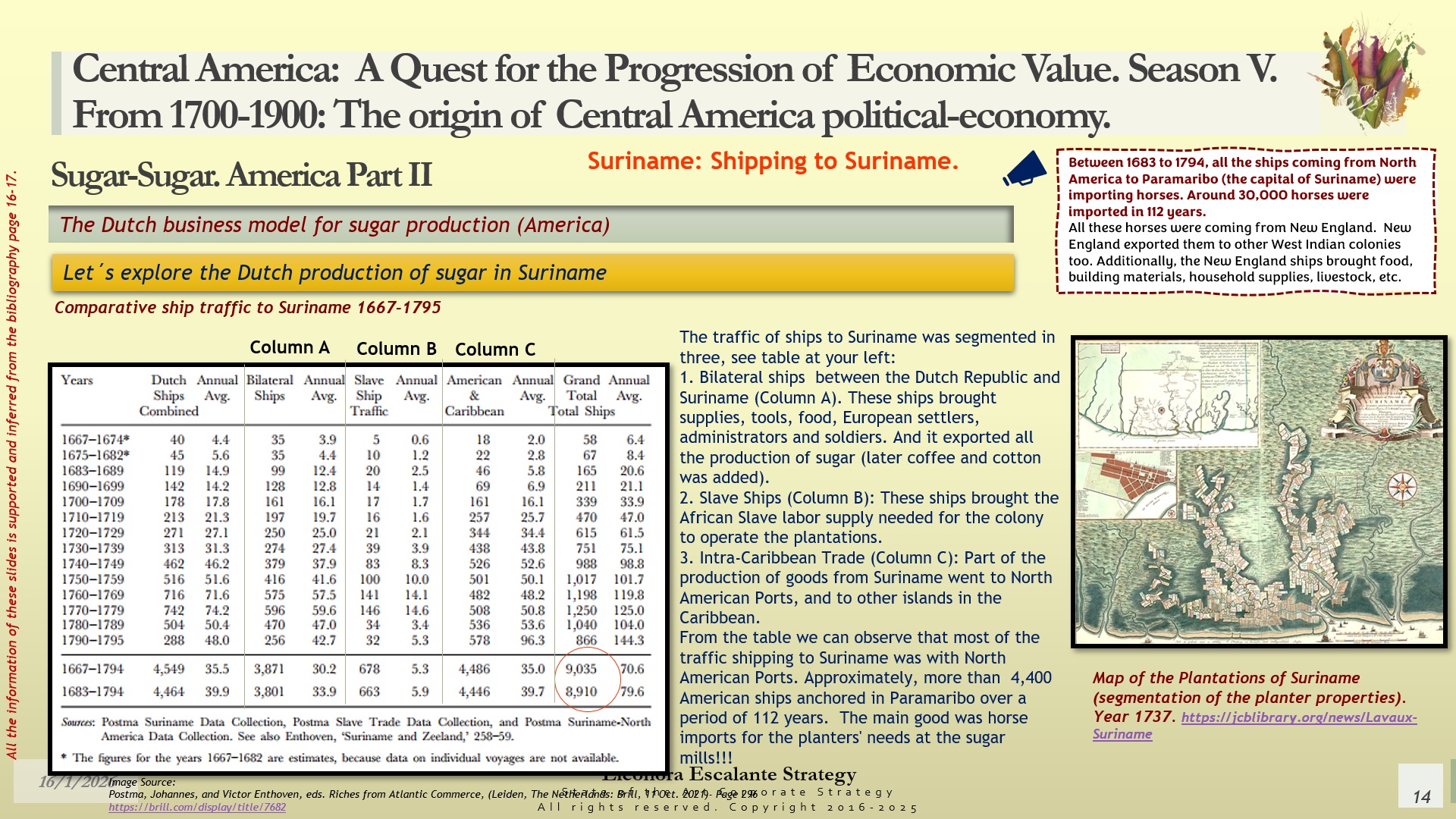

Shipping traffic to Suriname: Between 1667 and 1795, the traffic of ships to Suriname is well described and segmented under three categories: Bilateral ships, slave ships, and American-Caribbean Ships. These records are official. What about the illegal slave trade smuggling that wasn´t recorded? If the plantations of Suriname created a significant traffic of goods and slaves, particularly to North America and the rest of the Atlantic, where slaves were required constantly for their plantations and other infrastructure activities, how can we determine the extent of the illicit trading?. Read slide 14.

Slaves’ situation in Suriname. Slides 15 to 17.

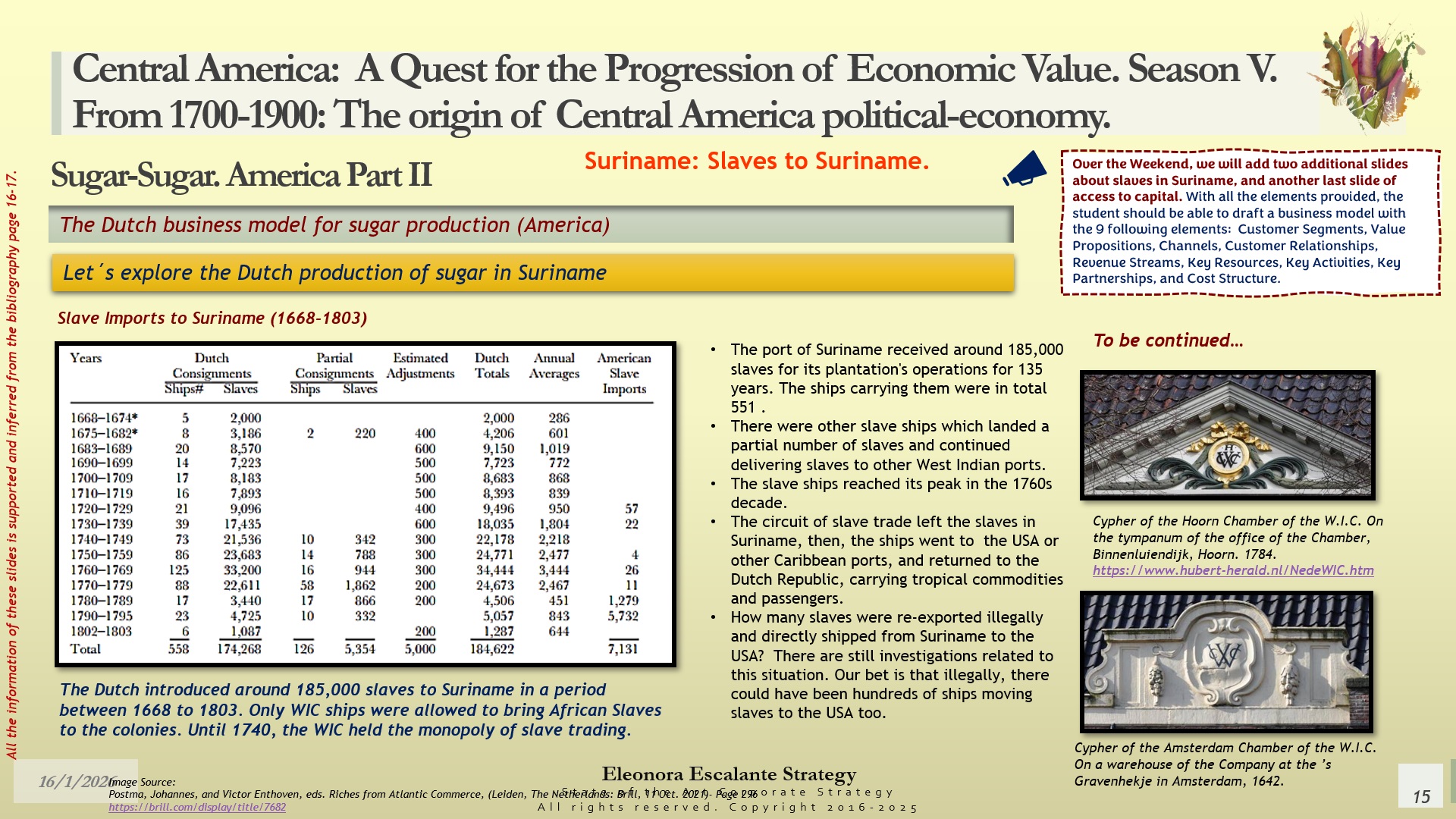

In relation to slavery, the slaves imported to Suriname between 1668 and 1803 vary according to the researcher. Postma (1) has validated around 185,000 slaves transported to Suriname; however, other authors raise that amount to 300,000 to 350,000 in total, until the last shipment in 1830. The reconstruction of the total number of slaves introduced into Suriname may be between 185,000 and 350,000 during a span of 162 years. What does this mean? It signifies that the Dutch were behind the rest of the empires in the utilization of slaves, because their territorial domains for sugar were small in comparison to the rest of the empires, or it also may mean that the amounts of slaves used for the plantations were lesser in comparison to the others. Whatever the situation, there are chronicles about the strength of the Surinamese Maroons (the Africans who escaped from the plantations to the Interior of the Guianas) who resisted the Dutch. Oostindie (2) lifts the rationale that marronage was substantial in Suriname (10%), and this affected the plantations’ indicators of productivity and profitability. Read again slides 15 to 17.

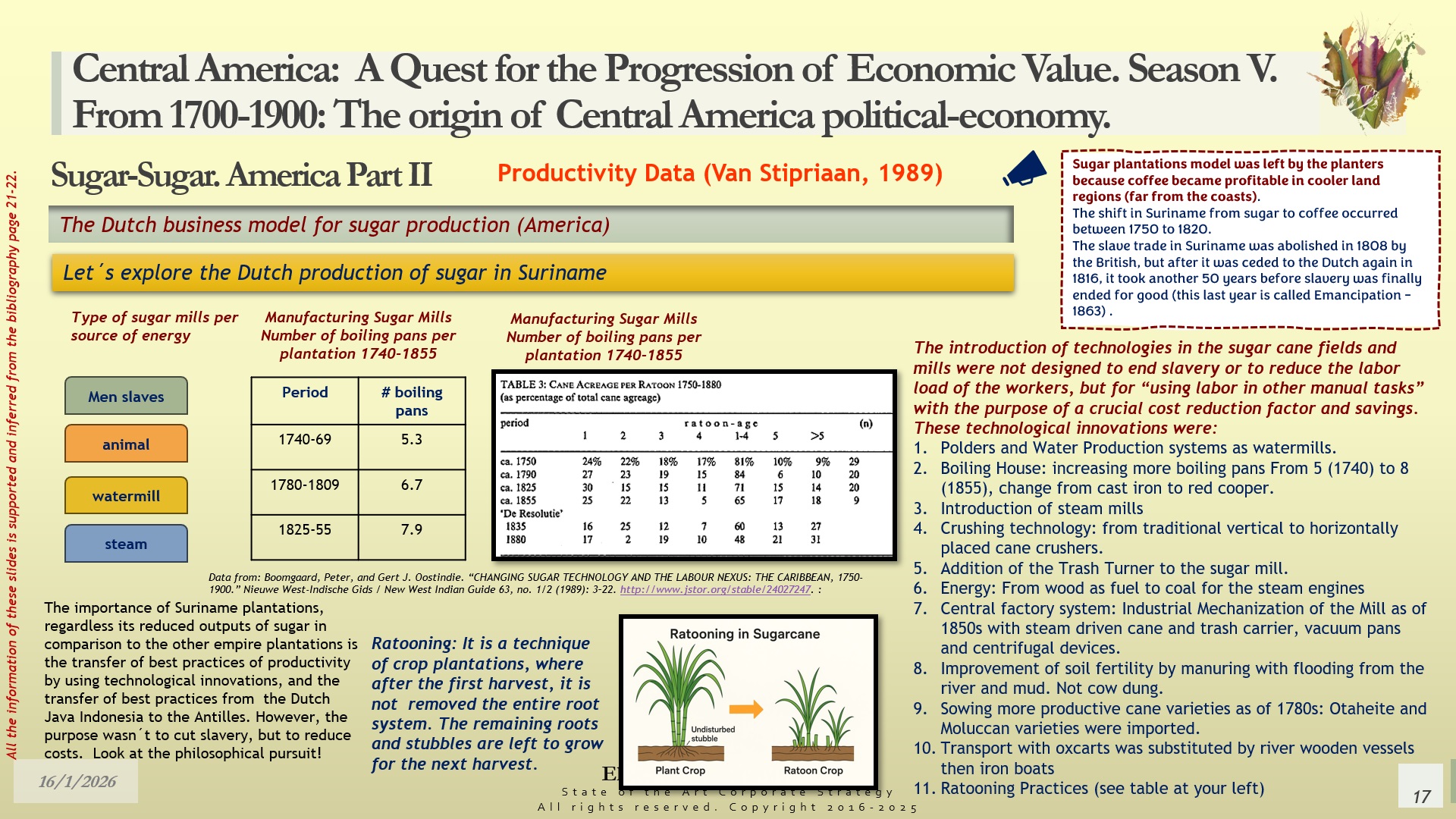

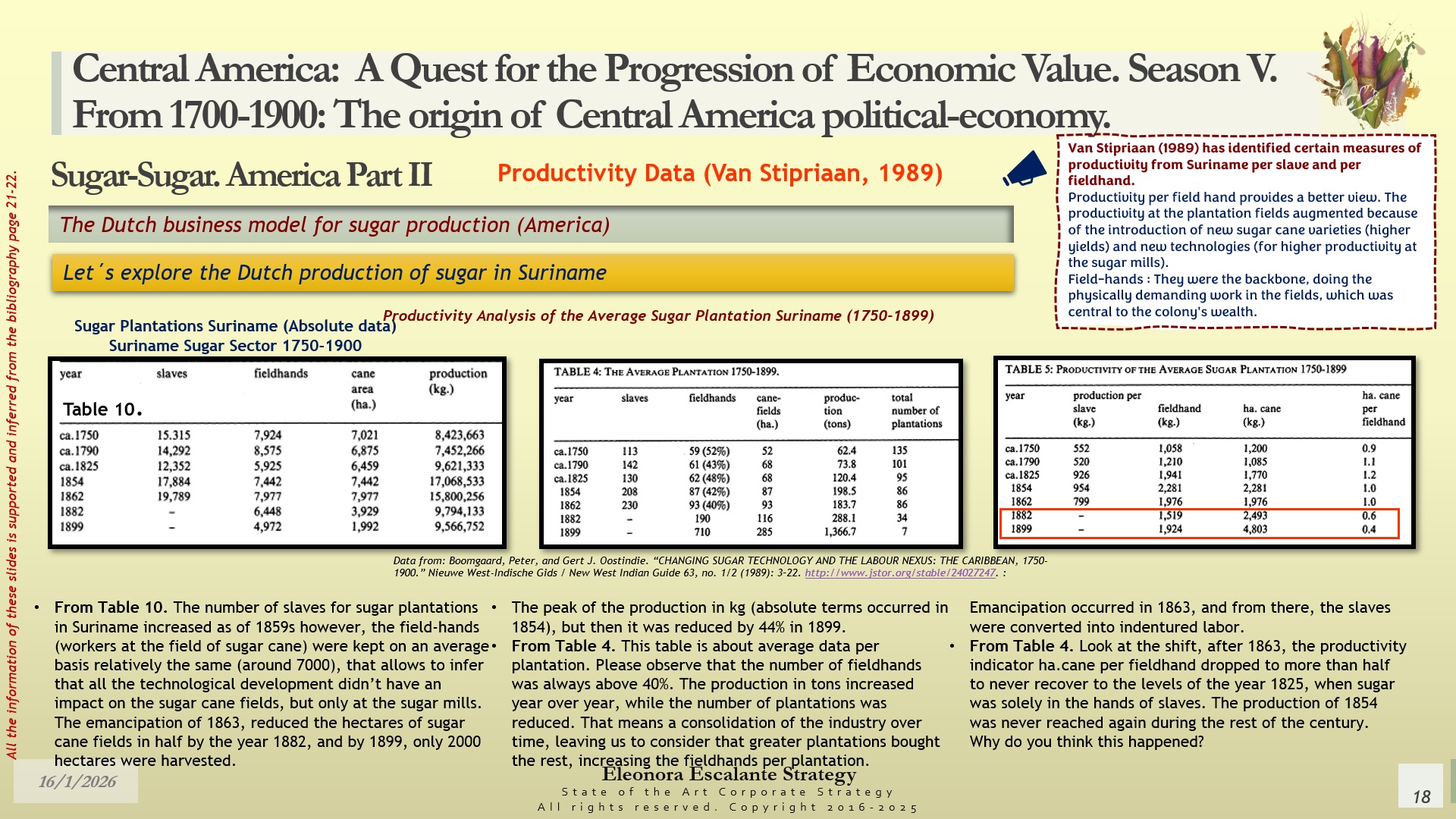

Dutch Sugar Plantation Productivity Data. Slides 17 and 18.

Despite that we have found lack of continuous information during the period of our study, Van Stipriaan (3) has provided a good perception of the Surinamese sugar situation. Plantation productivity indicators only make sense when comparing them with the rest of the competitive players. Our readers will have to wait a couple of weeks until we unfold the French, Danish, English, and Spanish numbers of productivity. In the meantime, these slides provided with our analysis are more than self-explanatory.

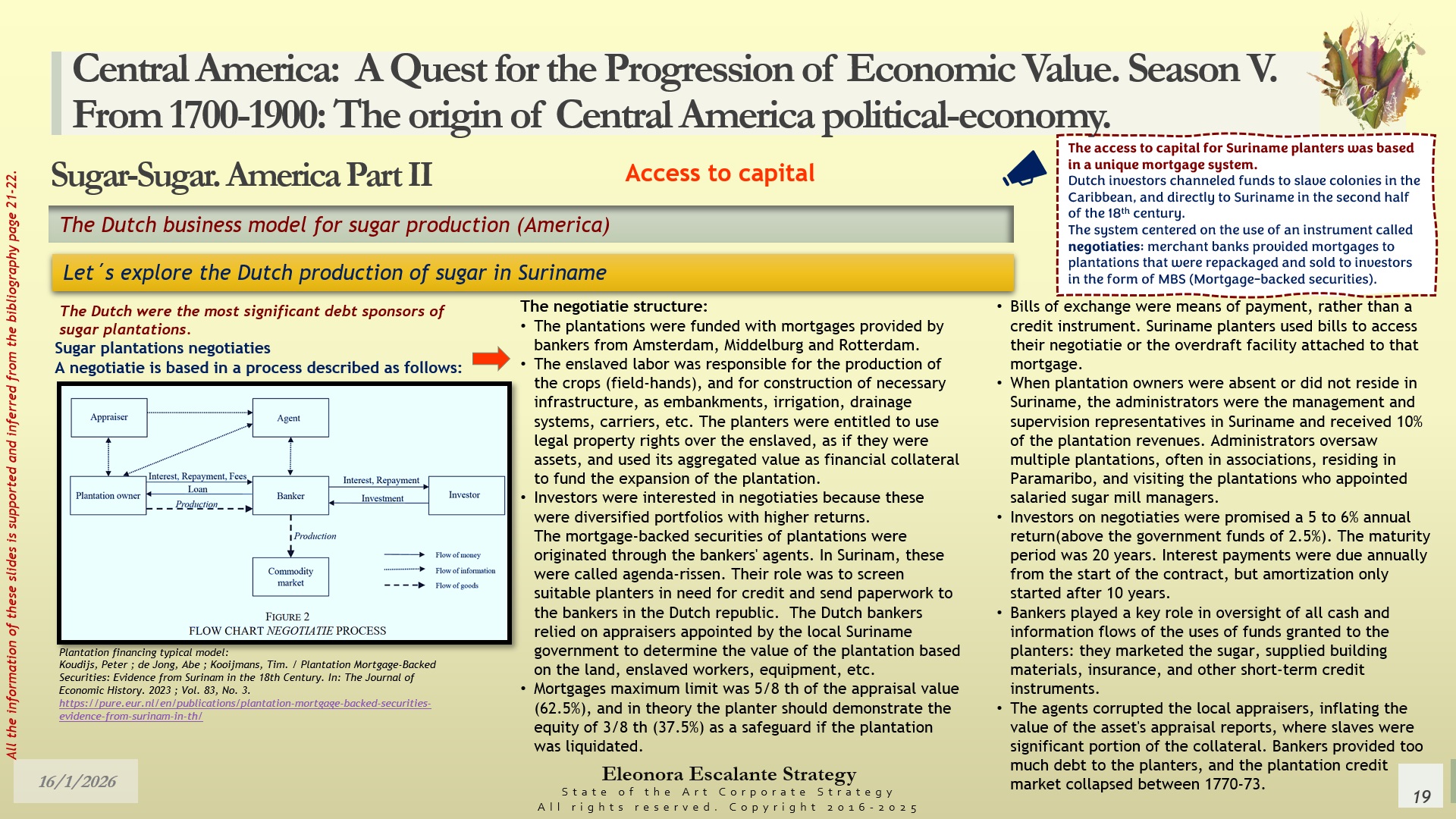

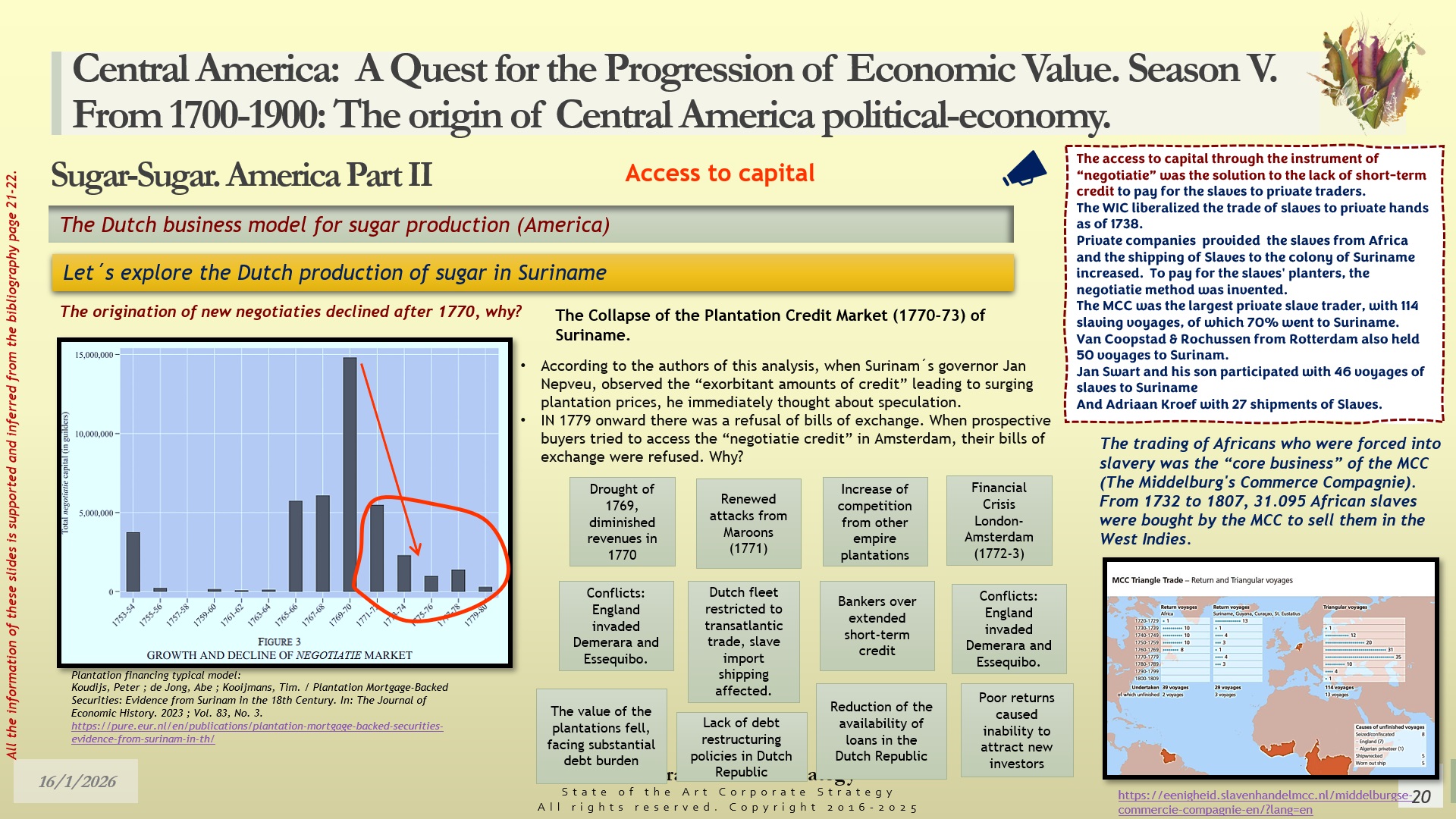

Access to Capital (Suriname) Slide 20.

This slide is also self-explanatory. Just remember that the MCC (Middelburg Commerce Compagnie) was a private corporation that was born for the Atlantic trade of slaves. That was its main purpose. According to Postma, after 1738, the Dutch West India Company (WIC) opened the Atlantic slave trade to the MCC, which became the principal Dutch slave trading company by 1746. The MCC was liquidated in 1889. That gives us a lot of years for slave trading reports that go beyond our imagination. Scholars Joannes Postma (4) and Herbert Klein (5) have written well-researched books about the Dutch Atlantic Slave Trade, and it is crucial for all my readers to continue reading about this situation.

To be continued…

Closing words.

This episode has been challenging. We have been filtering many books and sources of information regarding the engagements of the Dutch West India Company in America (WIC), and there are plenty of knowledge holes that we are still trying to fill. The WIC was the political and commercial arm of the Netherlands, utilized to expand its influence in the West Indies (this area corresponds to North America, the Antilles, Central America´s Atlantic Coast, the wild coast of Colombia, Venezuela, the Guianas, Brazil, and Western Africa). However, the Dutch were also engaged in Asia through the VOC (The Dutch East India Company). In terms of sugar, the Dutch were not enthralled in the business as much as they were engaged in the shipping of goods, including slaves, for the rest of the plantations of the empires. Ultimately, since the Dutch were privileged with a maritime supremacy (before Britain took the first place during the 19th century), it is undoubtedly true that the Netherlands used all this power (lawfully, illegally, and concealed under other flags) to distribute and re-export all the tropical products from America, mainly sugar.

Announcement. We have initiated a journey of comparing each of the 5 main empires’ sugar business models for production, processing, and distribution of the sugar cane. We are drafting most of the content using the fast-track method. There is additional information that I will prepare over the weekend, particularly in relation to access to capital and the review of the sugar production value chain of Suriname. However, be aware that the Dutch were also producing sugar in Asia, mainly on the island of Java, Indonesia. Our next chapter will correspond to the model of Britain.

Musical Section.

During our closing bonus season V, we will return to the symphonic philarmonic or camera orchestra compositions. Today, we have chosen the NJO National Youth Orchestra of the Netherlands. This is a concert of Johannes Brahms, at the Young Euro Classic Festival, celebrated in the Konzerthaus Berlin, 2018. An exquisite symphony. Enjoy!

Thank you for reading http://www.eleonoraescalantestrategy.com. It is a privilege to learn. Blessings.

Sources of reference and Bibliography utilized today. All are listed in the slide document. Additional material will be added when we upload the strategic reflections.

- Postma, Johannes M. (1990). The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600–1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. .

- Oostindie, Gert. “The Economics of Suriname Slavery.” Economic and Social History in the Netherlands, 1993. https://www.academia.edu/35408731/The_economics_of_Suriname_slavery

- Stipriaan, Alex van. “THE SURINAME RAT RACE: LABOUR AND TECHNOLOGY ON SUGAR PLANTATIONS, 1750-1900.” Nieuwe West-Indische Gids / New West Indian Guide 63, no. 1/2 (1989): 94–117. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24027251.

- Postma, Johannes. The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600–1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/dutch-in-the-atlantic-slave-trade-16001815/778CDAEC8F25E4C6901EA2576CFB5DB6

- Klein, Herbert S. The Atlantic Slave Trade. 2nd ed. of New Approaches to the Americas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. https://pueaa.unam.mx/uploads/materials/The-Atlantic-Slave-Trade-Herbert-S.-Klein.pdf