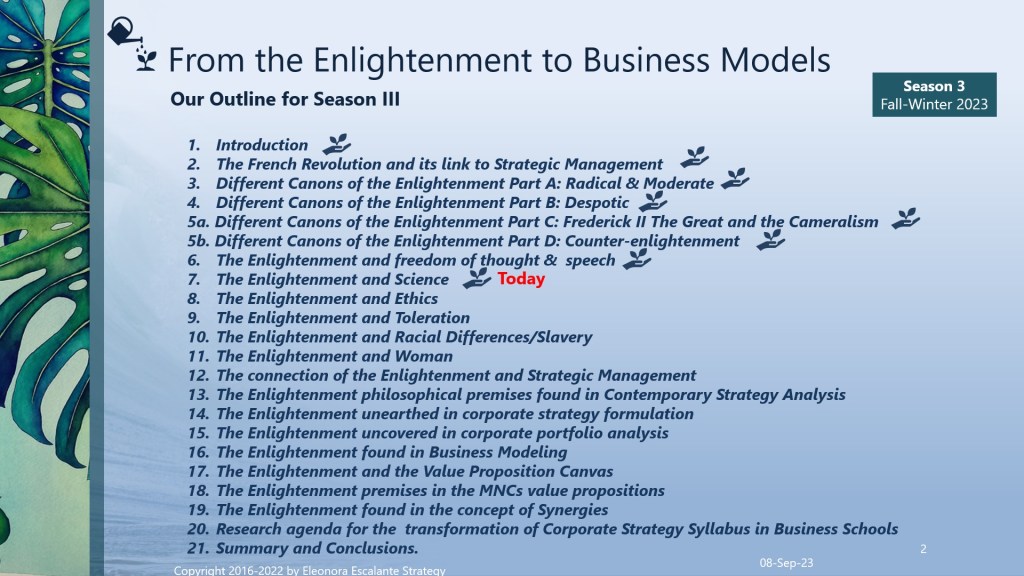

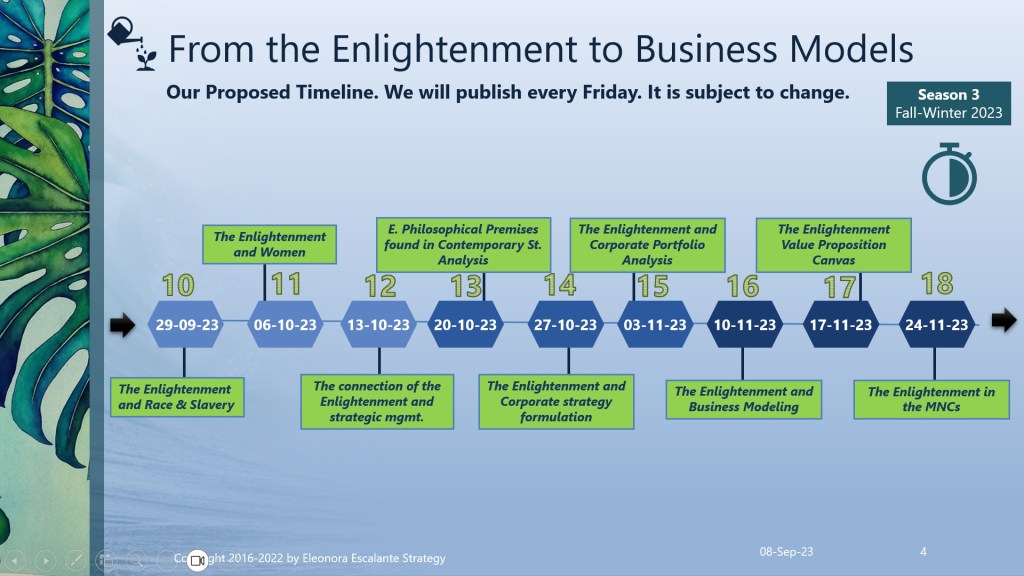

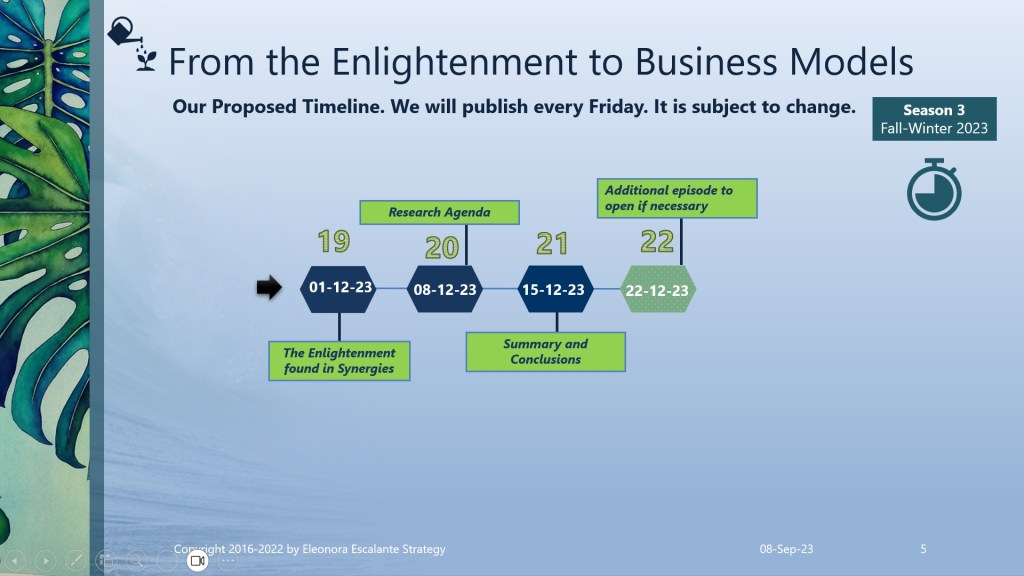

From the Enlightenment to Business Models. Season III. Episode 7. Enlightenment and Science.

Today is a long reflection publication that we expect you to cherish for the weekend. Let´s begin.

What is science?

The term “Science” from the point of view of a chronology of scientific historiographers is not what we may consider today. In our quest to distinguish the essence of “science”, let´s start with the premise that we are not going to be framed in its common definition: “Science is the observation, identification, description, experimental research and theoretical explanation of natural phenomena”. If you read the last sentence again and reflect on it for some minutes, you immediately grasp that science has been defined as a set of things or methods that science does. But I doubt this is the correct definition for us in the saga “From the Enlightenment to Business Models”.

If we ask any person on the street, no matter their level of education, the answer will always be about what science does. But not about what science is. Everybody knows what science does: “It experiments; it discovers; it measures; it observes; it frames theories which explain the way and the why of things; it invents techniques and tools; it proposes and disposes; it hypothesizes and tests; it asks questions of nature and gets them answered; it conjectures; it refutes; it confirms; it disconfirms; it separates truth from falsehood, it discerns from sense and non-sense; it tells you how to get where you want to get and how to do what you want to do”(1). But it is clear for us, that the definition of science for “what is science” won´t come easily, for the popular understanding as much as for the same doctors who produce science.

So, what is science?

Randomly I picked several academic papers written by professors during the 20th century, with the title “What is science”. Believe it or not, none of these researchers defined it in terms of its essence. All of them always made connections between different actions or performances of the term science, or how useful have been techniques or technologies coming out of science for the progress of humanity. The same scientists, philosophers of science, or historians of science focus on what matters for science from one side of the coin and still miss the other side. All of them go directly to answer the question of what science does and how science performs its ultimate purpose, but not what science is.

Let´s visit some of these peculiar definitions of science.

The Scientific American Journal edition of 1869 (2) defines the primary signification of the word science as knowledge comprised of facts and logical inferences from facts. Then the basis of all science is facts. Charles Singer (3) conceptualizes science as knowledge in the making. So, science in his view is a process inextricably wrapped up with research. Ernst Alfred Cassirer (4) a German philosopher with a Neo-Kantian Marburg influence, states that science is the last step in man´s mental development and it may be regarded as the highest and most characteristic attainment of human culture. For him, science is an abstract method to bring constancy and regularity to the world. L. Mumford (4) considers science as a driver of technology, a method to bring about practical changes in life. For Gregory Derry (4), science is the active and creative engagement of our minds with nature in an attempt to understand. Derry has written a book with the title “What Science Is and How It Works”, but only defines science in the epilogue, dedicating previously more than 300 pages to explain how science works: starting with ideas and concepts you know, observing the world, trying different things, creating a coherent context, seeing patterns, formulating hypotheses and predictions, finding the limits where your understanding fails, making new discoveries when the unexpected happens, and formulating a new and broader context within which to understand what you see. C.M. Jackson (5) starts by explaining the historic evolution of science, that came slowly developed since the ancient wise Plato and Aristotle, continuing with Descartes, and then jumping into the methods of science outlined as follows: (a) Observation; (b) Classification; (c) Testing; (d) Measurement; (e) Experimental method. Waterman (6) expresses that to understand science, it is important to understand what scientists and historians of science have meant by the term science. By doing this, Waterman shows us different book authors that have written about it. Max Wastorfsky (7) explains to us two main approaches to understanding science. One is the study of science itself as it is taught in our liberal education systems from elementary school through college. On the other side, he conveys that the study of science is the study of the conceptual frameworks of science, as the instruments of scientific understanding, or the ways in which the scientists come to understand the world of their inquiries. For Wastorfsky, conceptualizing what science is requires studying the philosophy of science which may be characterized as a study of the conceptual foundations of scientific thought. George Coyne S.J. (8) defines science by asking what does science try to do? He continues with the objective of the sciences: to seek natural causes of natural phenomena. If causes are not found, a science gap is born. Scientists will continue to search, generation by generation, until the “God of the gaps” surrenders to a natural explanation. J. D. Bernal (9), considered the founding father of the science of science, views science as a social activity, integrally tied to the whole spectrum of other social activities: economic, cultural, philosophical, and political. Bernal lists different aspects of science, defining it as an institution, a method, a cumulative tradition of knowledge, a major factor in the maintenance and development of production, and one of the most powerful influences molding beliefs and attitudes to the universe and man. Nicholas Maxwell (10) argues that science has solved the issue of learning about ourselves and the universe, but we urgently need to know how to create a civilized world.

D. Acemoglu from MIT, in his last book “Power and Progress” (10), defines science as the foundation for economic progress with the purpose of solving our problems. However, he remarks that the commercial applications of science are not solving the most current problems and the urgent needs of the people. His book studies scientific innovations considering each invention as a business venture, that today is enriching a small group of entrepreneurs and investors, whereas most people are disempowered and benefit little. Finally, there are several authors that define science only in terms of the disciplines that have been created and have been added over time.

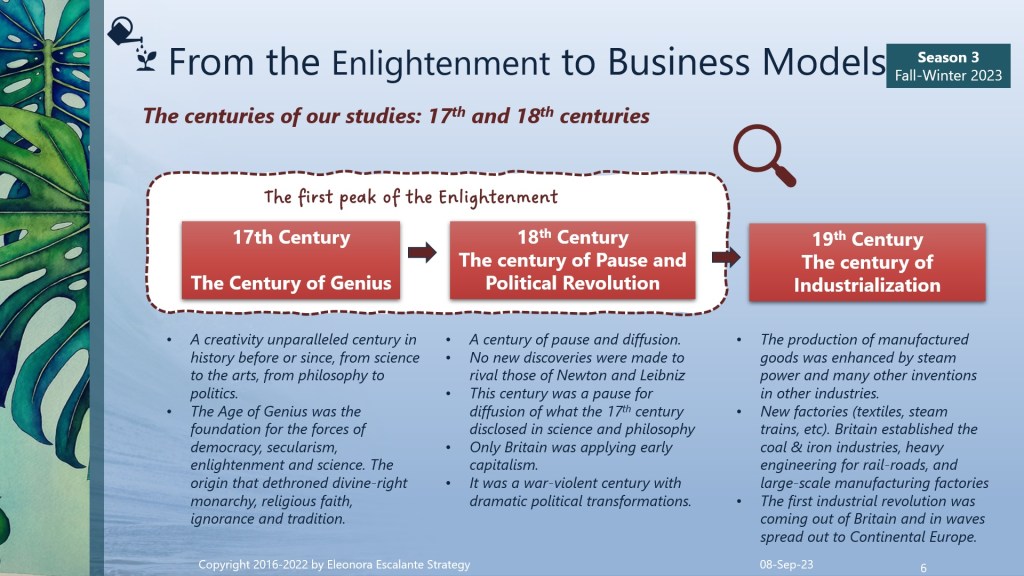

For Eleonora Escalante Strategy, the term “science” in its essence, can´t be conceived as a knowledge of facts, or as the frameworks of study, or as the list of disciplines that are categorized as sciences. In addition, we can´t see science as the commercial application of all the inventions that have changed our societies (some for better, others for worse). During the 16th and 17th centuries of the Age of the Enlightenment, which has not stopped yet, the scientific revolution was mainly in the hands of philosophers who were scientists: Francis Bacon, Robert Boyle, Nicolas Copernicus, Rene Descartes, Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, Gottfried Leibniz, John Locke, and Isaac Newton. These Masters of Science were philosophers of science, backing up their first role with the second role of scientists. Through their discoveries they were trying to explain the natural phenomena, trying to gather reasons to explain the natural world beyond superstition and religion, beyond the dogmatic nonsense of old paradigms. The 17th century called the “Century of Genius”, occurred in parallel to the inventions that were answering the priority needs of publishing the discoveries of that Generation. However, the Geniuses of the Enlightenment were fascinated to spread out the news later during the 18th century. A century of pause that triggered the French Revolution.

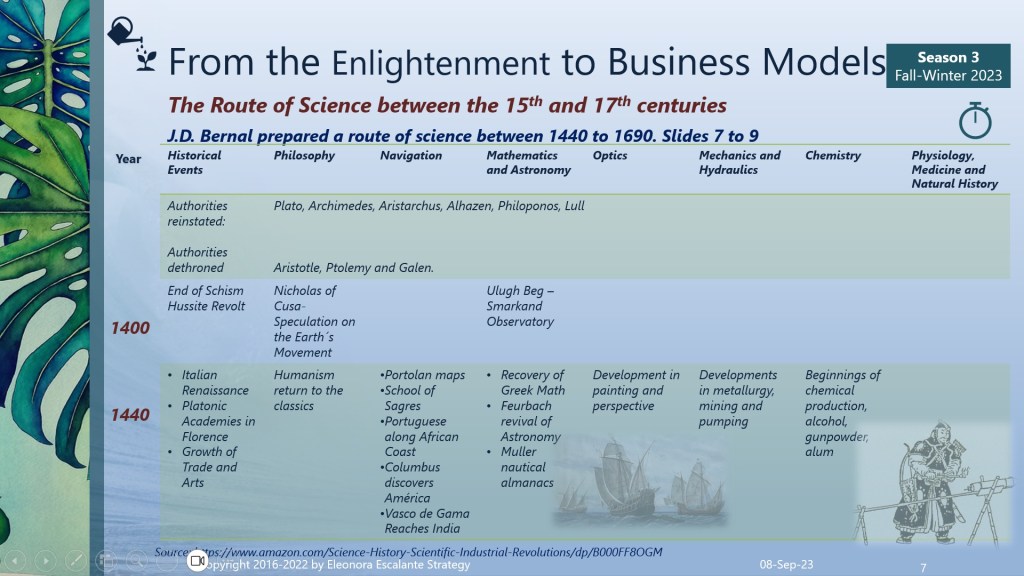

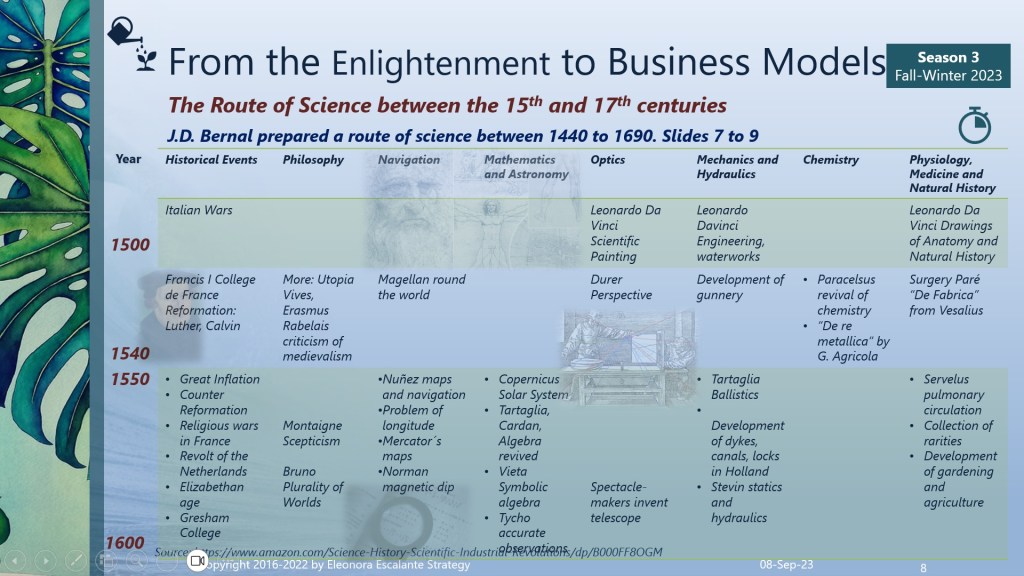

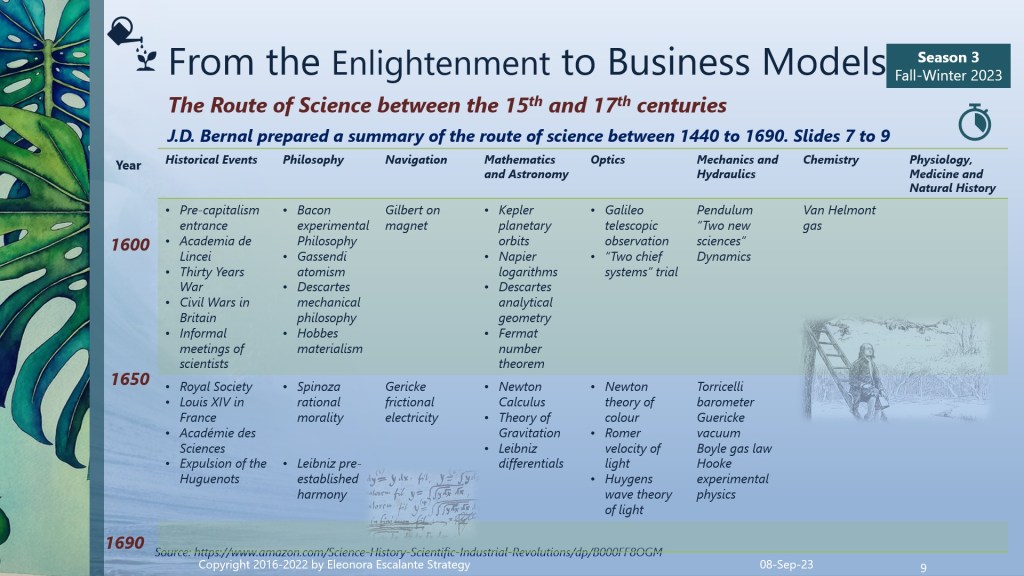

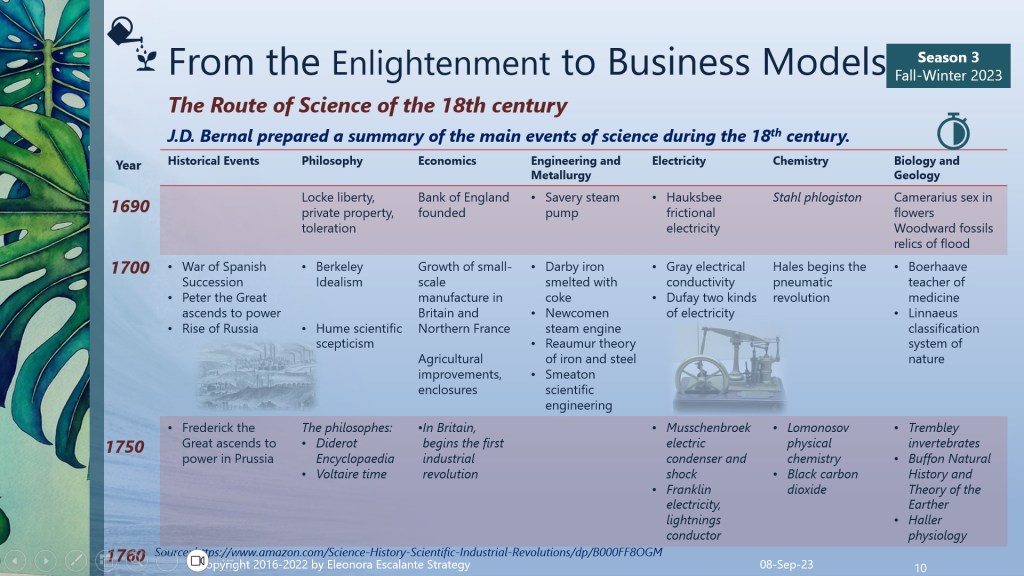

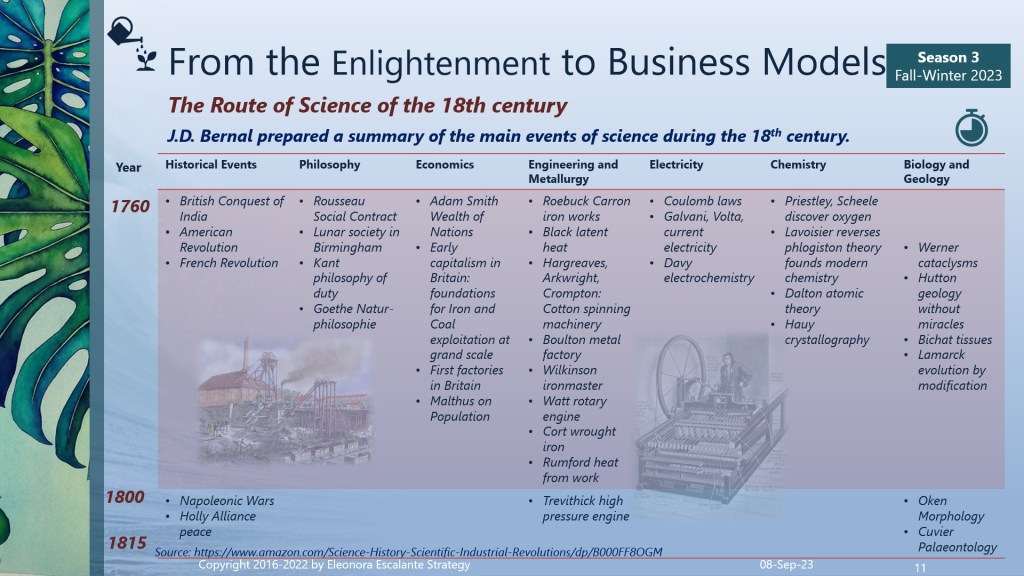

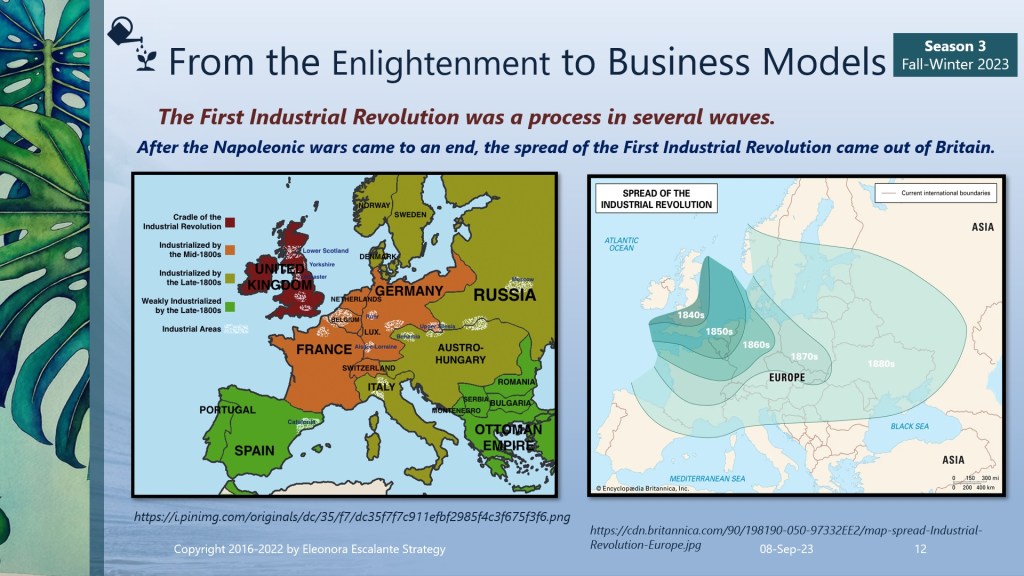

When the 18th century closed its time, Britain was starting its journey as the cradle of the first Industrial Revolution. And then, the 19th century opened its gala to the Gilded Age or the first-ever century of industrialization on the planet. Look at slide number 7.

This transition (see slide above), from the Century of Genius (17th century) to the Century of Pause and Revolution (18th century), to then the First Century of Industrialization (19th century), is the core of our studies in this saga.

What occurred to the meaning of science between the 17th and the 19th centuries? The Renaissance and the Century of Genius weren´t inspired by the locomotion of making inventions for profit. These scientists and philosophers could barely make a living with their science projects unless they came from an aristocratic background or they held a patron of power. But something occurred after the century of pause and French revolution: The rulers and most prominent merchants who were educated, began to see themselves as the potential captors of those new inventions. The patronization of science began in the 17th and 18th century. Common people didn´t understand what Newton or Leibniz or Euler did, but they realized for the first time that in order to make “good science”, much study was needed. That was the time in which science began to be recognized as a lifetime career of research. The kings or queens, the princes, and the rest of the high-rank “well-educated” nobility of the 18th century not only promoted the academies of sciences and contests; but wanted increasingly to see the last advancements of discoveries in science to apply them to war and urban engineering. To acquire military strength for war, and to improve their exploration and discoveries in the navigation to the new world. But the factories and exploitation of natural resources using scientific technologies weren´t on the horizon yet, with the exception of Britain.

The concept of science changed in the 18th century. It occurred at the peak of the first phase of the Enlightenment. It coincides with the advent of cameralism. The geniuses committed to science were seen as useful tools for gaining inventions that could work to make money. As the British did with the coal and iron inventions. The appetite that triggered science began to be explored under the utilitarian premise of usefulness, and during the 19th century, scientists began to confuse their aspirations for helping others and swapped them for commercial inventions that could raise profits for the patrons who sponsored their work. Science lost its ultimate cooperation purpose in the 18th century, and it spread out the “for-profit motive” during the 19th century. The confusion began when scientific discoveries, (and their respective techniques, as machines) became the foundation for economic progress. Science started to be seen as a medium tool for the profits of those who patronized the scientists. It was here when science lost the cooperation roadmap and turned into a competition method for profits. It was during this time that the philosophy of science of the first Enlightenment masterminds began to fade.

Let me show you this idea in a timeline of science, according to J.D. Bernal. If you wish to print or download the PDF slides do not hesitate to do it.

When Science Happens:

Science as a continuum of cycles of discovery, consolidation, pauses, re-learning, and applications.

Since the Renaissance, scientific research and the philosophy of science were considered as working together. None of the geniuses that we have named in the slides above were doing science with the goal of the acquisition of new powers through their new discoveries. None of them. None of the Enlightenment profiles that we have seen here since January dedicated their lifetime and risked their lives to printing books with their inventions with a utilitarian purpose to maximize shareholder´s value as a source of profits. These guys were working, publishing, debating, and consolidating their knowledge under the Inquisition and official persecution because their aim was to demonstrate that natural phenomena and the essence of our existence could be explained differently than tradition. After they spent years using the outstanding scientific methods of their times, the scientists of the Century of Genius were interested in publishing their results for its diffusion to everyone who could read. They wanted a change that could allow people to be free of the ignorance. For those scientists who did not have patrons from the Governments and the nobility, the best thing that could happen to them was to win a contest at the Academy of Science in their cities, to gain some fame by meritocracy to attain a sponsorship that could make them afford their living expenses and continue with their scientific proceedings. The motives to publish science were pure motivation for a recognition of the scientific peer’s community. Once the Age of Industrialization arrived (19th century) the next generations of scientists’ purposes were completely different than the Enlightenment scientists.

Science growth was a slow process.

From observing the timeline of science above, from the 1400s up to the 1800s, we can infer that the main scientific events did not occur as a revolution, but progressively tied to the progress and expansion of the Universities and centers of Education in Europe. The Jesuits’ arrival to education only occurred after 1540, when Pope Paul III granted them official approval as the Society of Jesus (12). The founders of the Jesuits, including Ignatius Loyola (d. 1556), all held Master of Arts degrees from Paris. From 1540 to the year before their expulsion from Europe (during the Enlightenment), the Jesuits expanded an extraordinary network of universities and schools that offered the medieval core curriculum and additionally the new humanism of philosophy, history, and performing arts. In the protestant segment, John Sturm (d. 1589) founded a gymnasium in Strasburg and also promoted a new model of education: classical eloquence, piety, and citizenship in support of Christian values. In addition to the Jesuits, and with Sturm’s influence, Erasmus and Zwingli also helped to expand Christian humanism and touched almost all educational institutions in Europe.

So, the scientific revolution was a progressive quiet process of acquisition of knowledge and development of thought tied to the expansion of high-superior education in Europe. It was a slow, but well-proven, debated, and verified process. It was built under a lengthy timeline route map in waves or cycles of discovery, consolidation, pauses, re-learning, and aggregated applications to explain natural phenomena of different domains.

Science has always been built in generational cycles.

It has been developed on the ideas and methods of past ancestors, stimulated by new understandings of ancient texts, and it was always linked to the philosophy of science. These are called cycles of scientific pausing. Cycles of rebuttal of the old with a well-proven scientific refutation, and the emerging of the new, endorsed and accepted by several generations of the whole scientific community. The denial and rejection of Aristotle’s authority in many subjects, or Galen and Avicenna refutations; took place from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. The approval of the new had the highest standards that were not moved by money but by scientific truth. The scientific revolution took place in between 2 to 3 centuries. It wasn´t automatic. And it coincides exactly with the time in which the Jesuits arrived into the educational drama, from the 16th up to the 18th century.

I won´t spend time providing long descriptions of the scientists who built this scientific mayhem, but we must be conscious these scientists were the essential foundation of it. The most relevant information about them is as follows (13 and 14):

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543). Polish. Studied at the Universities of Cracow, Bologna, and Padua. His background: astronomy, history, literature, economics, and physician, with expertise in canon law.

- Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564). Flemish. Studied at the Universities of Leuven, Paris, and Padua. His background: Ancient Greek and Medicine. Imperial Physician in the courts of emperors Charles V and Phillip II.

- Johan Kepler (1571-1630). German. Studied at the University of Tubingen, excelling in math and astronomy. The successor of the Danish Astronomer Tycho Brahe in Prague, within the lands of the Holy Roman Empire.

- Galileo Galilei ( 1564-1642). Italian. Studied Medicine, Math, and Astronomy in Pisa; while teaching art on the side. He then became a professor at the University of Padua. He championed the heliocentric theory of the solar system and was famously condemned by the Roman Inquisition in 1633.

- Francis Bacon (1561-1626). English. He studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, and at Poitiers in France. Philosopher of Science, Jurist-lawyer, politician, and Champion of popularizing the new scientific methods.

- Isaac Newton (1642-1727). English. Studied at Trinity College and Cambridge. Academic, Scientist, Government Official, and Court Official. Developed Calculus, and the law of gravitation. His areas of domain: Applied Mathematics, Navigation, Metallurgy and Optics.

- René Descartes (1596-1650). French. Educated in science and math at the Jesuit College at La Fleche. With a canon law degree at the University of Poitiers. He also studied in the Netherlands at the Universities of Franeker and Leiden. Teaching at Utrecht University.

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716). German. He studied math, natural philosophy mechanics, law alchemy, and geology. Educated at the University of Leipzig, Jena and Altdorf. His patrons were from the Court of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, Brunswick, Brandenburg, Mainz, Wolfenbüttel, and Hanover.

When the 17th century, the Century of Genius or Enlightenment unfolded, the educated critical mass of people coming out of universities was enough in quantity and quality to understand, or at least to realize that science was good enough. And it was used to transform a past of misery. Science was developed in intermittent cycles of invention, consolidation, pauses, and re-learning. But with industrialization, during the last part of the 18th century and during the 19th century; the conceptual frameworks of scientific discoveries were accepted to be applied in the incipient industries of iron and coal, heavy construction engineering (such as railroads), large-scale factories, and other manufacturing pioneer oeuvres. If you look at it from a high perspective, it was simply the first intent to apply scientific techniques to organize society in a different manner than the old regime.

Enlightenment and Science. A new perspective.

We can infer from our state-of-the-art philosophical research that the medulla or the core relationship between the Enlightenment and Science rests in the character of the radical transformation of the fundamentals of understanding what is science and how to work with it. The First peak of the Enlightenment (17th-18th centuries) marks an accumulated series of scientific events that triggered a before and after in the foundations of science. That is why, erroneously, it is being baptized as the scientific revolution period in our history. But for us, the revolution wasn´t instantaneous. The Science and the Enlightenment relationship was a process that took several centuries. We can´t consider it as the French Revolution that suddenly replaced the old with the new. It wasn´t as such. It took a continuum process of several philosophers of science who decided to become scientists, and they procreated the most impeccable concepts and conceptual frameworks that later were used for the century of the first Industrial Revolution that helped to create the modern world in which we live. The first intent to apply these theories and science went for capitalism.

Technological innovations are only used to make money, not to raise science.

It wasn´t the Enlightenment that provoked the system of incipient capitalism in the industrialization era. What happened is that Capitalism (or the theory of Adam Smith) was blindly used in Britain at that moment, and from there, it propagated to other countries in Continental Europe. The methods for manufacturing utilized in the 1700s were concentric to the hand tools of the artisan. In the pre-industrial era, the artisan master’s entrepreneurial shops were the norm. Suddenly the new mechanized manufacturing, as a characteristic of industrialism, commenced to require precision machine technologies to manufacture the standardized, massive production, with the help of steam power. The entrepreneurial skilled artisan master shops ethos was slowly replaced by a new emerging mechanical culture of the factory, where special machine tools replaced the artisan´s hand tools. The operational aspects of these new models of machine production became the new symbols of capitalism, wealth, and progress, against the artisan workshops. The large-scale results of the factories’ “production in terms of profits, created a need for new inventors of machines”. Governments encouraged inventions with the new patent system in place, through contests and awards for targeted technologies that could serve well the newest industrialists. Increasingly during the 19th century, the concept of science of the Enlightenment age was completely lost. The new inventions or technological development of machines were seen as a profit mechanism for anyone who could afford the endeavor, and this was that moment in time in which the term science got prostituted by money. Science was not a discovery process of natural phenomena anymore. Science started to be used by those who can make the most out of it.

Don´t take me wrong, please. It is true that science has been created for our needs and wants. But it is also true, that science has been manipulated over the last 2 centuries, not just to bankrupt the artisans, but to create the most irrational products and services that will end up killing us as a civilization: nuclear bombs, weapons, oil and gas, and lately: the technological NAIQIs (Nanotech, Artificial Intelligence-including automation and robotics, Quantum tech and the Internet).

Let´s move to the 21st century. To invent a platform for videos such as YouTube, or to invent an artificial intelligence tool to write, or to apply generative artificial intelligence to perform digital drawings, and paintings, or to gather a tool for networking and instant communications such as Facebook, Instagram or Twitter is not rocket science at all. These are technologies that are not well designed, nor have passed the strict tests of scientific reviews. These technologies arose with the goal of making viral information and the guideline to make them ubiquitous was simply taken from a marketing consumer-driven disruption theory. It has nothing to do with science. “If you want to be wrong, then follow the masses”. Socrates.

Are we managing our new scientific discoveries well?

We can conclude from this episode that humans have distorted the concept of what science is since the century of industrialization (19th century). We have carried a wicked purpose of making profits through science, and we have confused the technological tools (which are simply gears or utensils) with the meaning of “science”. To be a true good scientist should take us back to the spirit of the founders of the Philosophy of science, before and during the first peak of the Enlightenment.

The last paragraph is not just our reflection on what is coming out since the Y2K. There are hundreds of “good scientists” and professors all over the world who truly promote science for the benefit of the majority, for finding cures to sicknesses, or to combat climate change. On the other side, the tools of the technologies (which are commercially driven) have continued knocking on the door of venture capitalists to make them a successful endeavor for profits. Who is moving the world? Science or the tools of science erroneously designed?

Our commitment is with the good scientists who have not lost their way yet. Our commitment is with professors who still have the valiant attitude to say what we have written today. Science’s ultimate purpose has been lost and substituted for an irrational quest for profits. During the last 50 years, it has been generally accepted that every new inventor or innovator in disruptive technologies is a profit maker, leaving science not just out of the map, but utilizing it and manipulating it only to convince the public under a consumer-driven value proposition. Without a doubt, I can assert that everything (or at least 95% of products and services coming out of the hub of technological development) are guided by the venture capitalists’ standards that do not concern about the spirit of the original scientists who were philosophers of science in the first peak of the Enlightenment era.

The spirit of the Founders of Science is seriously necessitated more than ever in our times. Progress with the original spirit of Scientists, those who opened up the definition of science (since the Renaissance to the Century of Genius) can be attained again, if we all insist on doing it for the sake of loving God, loving others, and loving the planet, cooperating together to help the world to become a better place.

Announcement.

Our next publication will be next Friday 15th of September. We will continue our journey with the topic: “The Enlightenment and Ethics”. Blessings and thank you for reading our episodes.

Musical Section

We have decided to continue sharing classical flute magical music that was composed, released, or performed between the 17th and 18th centuries, to accompany your readings.

Today our musical video is from Brilliant Classics, a compilation of several beautiful melodies for flute and harp. The Artists: Andrea Manco (Flute) who is also Director of the Flute Academy at the Fondazione Accademia Internazionale di Imola “Incontri col Maestro”. Andrea is considered one of the best flutists of his generation. The second artist is the harpist Stefania Scapin (Harp). She has studied at the Conservatory of Music in Udine, the Royal Academy of Music in London, and at the Universität für darstellende Kunst in Vienna. Stefania is raising money to buy her new harp. If you wish to help her, click here https://www.maecenates.org/en/a-harp-for-stefania-fundraising-campaign/

Enjoy the music composed by Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, and Gabriel Fauré.

Thank you for reading http://www.eleonoraescalantestrategy.com

Sources of reference utilized today.

- Wartofsky, Max. “Conceptual Foundations of Scientific Thought”. McMillan, 1968. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/philosophy-of-science/article/abs/marx-wartofsky-conceptual-foundations-of-scientific-thought-an-introduction-to-the-philosophy-of-science-new-york-the-macmillan-company-1968-xii-560-pp/AC9F51605BCABFECFED077CA4C21915B

- “What is science”. Scientific American, Vol. 20. No. 1. January 1860 page 10.

- Singer, Charles. “What is science?”. The British Medical Journal, 1921. Vol 1. NO. 3156. Page 954

- Derry, Gregory. “What science is and how it works”. Princeton University Pres. 1999. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691095509/what-science-is-and-how-it-works

- Jackson, C.M. “What is science?”. Sigma XI Quarterly, September 1930 Vol 18, no. 3. Page 77-86

- Wartofsky, Max. “Conceptual Foundations of Scientific Thought”. McMillan, 1968

- Waterman, T. “The citizen and the history of science”. American Scientist, Sigma Xi. Vol 39. No. 3. 1951. Pages 459-461.

- Coyne S.J., George. “Evolution and Intelligent Design. What is Science and What is not?” Revista Portuguesa de Filosofía, 2010. T. 66. Pages 717-720.

- Zhao, Y.; Du, J.; Wu, Y. “The impact of J. D. Bernal´s thoughts in the science of science upon China: Implications for today´s quantitative studies of science”. QSS. MIT Press. 2020.

- Maxwell, N. “Science and Enlightenment: Two great problems of learning”. Springer, February 2019

- Acemoglu, D. And Johnson, S. “Power and Progress: our thousand-year struggle over technology and prosperity”. Hachette Book Group, Inc. 2023

- Moore, John C. “A brief history of universities”. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-01319-6

- http://galileo.rice.edu/index.html

- https://www.amazon.com/Brief-History-Universities-John-Moore/dp/3030013189

Disclaimer: Eleonora Escalante paints Illustrations in Watercolor. Other types of illustrations or videos (which are not mine) are used for educational purposes ONLY. All are used as Illustrative and non-commercial images. Utilized only informatively for the public good. Nevertheless, most of this blog’s pictures, images, or videos are not mine. I do not own any of the lovely photos or images posted unless otherwise stated.