Central America: A Quest for the Progression of Economic Value. Season IV. Episode 2. Derailment of Violence and Inner Conflicts between Spaniards and Central American Indians.

Dear Beloved Readers:

Welcome back to our Friday literature dispatches for you. Our publication today is about a prelude, an opening to the rationale, or why the Spaniards did not dwell in a pacified Audiencia of Guatemala territory, despite all the efforts of the Catholic Friars and the Inquisitorial Terror of the guard authorities over the Central American Native Populations. We have focused our attention on the Mayan communities; however, the rest of the countries also held other indigenous villages, which were squashed, little by little, by a mixture of oppression, encomienda-repartimiento mistreatment, illnesses, and lack of a secure place to live.

When Imperial Spain designated that Native Indians of Spanish America were free subjects to the King of Spain, that doesn´t imply that they were free citizens. The local Central American peoples were not even considered “legal people” with legal rights until after the Independence movements of 1821 and, in some cases, past the mid-19th century. The significance of this situation is of gigantic impact, because by law, and without exception, the indigenous people couldn´t sell or buy properties. All the land belonged to the King of Spain, and he was the only one who could reward or grant the possibility of the concession of it. We have drilled on this topic since the conception date of the encomienda system. We have dedicated several slides to explaining in detail how the Spaniards colonized the Mayan Indians. The source of conflicts between Spaniards and Indians after the conquest was as clear as the water: the natives were left out of their beloved land. They had nowhere to stay. Nowhere to live in harmony with their original values, either. And since they were not considered citizens of Spain, under the Audiencia de Guatemala quarters, it was one of the most heartbreaking experiences not to have a place to dwell anymore. Our analysis of the evolution of land tenure in the Kingdom of Guatemala is an essential part of our publication. However, even in the middle of so much pain, sorrow, and distress, the Natives found a certain type of shield in the Catholic Church. The different monastic orders were sent expressly to protect them (not perfectly, of course), but there was an effort which, depending on the temperament and character of the priest or the friar and his relationship with the community congregation, the Natives felt more or less loved and cared for. Some Indigenous communities of Central America were protected and respected with true love from God, while others were not. And there is a huge paradoxical range of testimonies in that research direction.

Today, as part of our contextual introduction, we have also elaborated a chronology of the main events in the Kingdom of Guatemala (from 1540 to 1860). Finally, as crucial facts to remember, we have summarized the main relevant elements to not forget. With the presentation slides shown below, it is our aim to provide a general explanation of the conflicts between Spaniards and Native Central American peoples. We perceive a much complicated scenario of quotidian violence and persecution in the highlands of Guatemala that probably has not been disclosed yet, or it has been hidden on purpose. Thanks to God, the safeguarded Montaña region was a unique refuge for those who survived.

Let´s proceed to read our frame of reference. Feel free to pass it to all your people. Print it, and ask yourself questions, please. Follow the bibliography. There are plenty of URL links that you can follow over the Internet to grasp an outstanding picture of why we have not landed in specific conflicts during this period of analysis.

We request that you return next Monday, September 29th, to read our additional strategic reflections on this chapter.

We encourage our readers to familiarize themselves with our Friday master class by reviewing the slides over the weekend. We expect you to create ideas that might be strategic reflections or not. Every Monday, we upload our strategic inferences below. These will appear in the next paragraph. Only then will you be able to compare your own reflections with our introspection.

Additional strategic reflections on this episode. These will appear below on Monday, September 29th, 2025.

Contextual Introduction Colonization of the Kingdom of Guatemala. Slides 4 to 6.

The Colonization of the kingdom of Guatemala has been depicted by historians as a process executed right after the conquest. It started in 1524, when Pedro de Alvarado conquered the southern part of what is now Guatemala and El Salvador. This area is called the Highlands (see slide 6). Nevertheless, let´s not forget that the Spaniards were conquering the rest of the region in parallel to what Pedro de Alvarado was doing. We have identified at least three phases of colonization of Central America:

- Early Phase: From 1524 to 1700. The Spanish Habsburg Kings period.

- Middle Phase: From 1700 to 1931. The Bourbon kings’ period.

- Late Phase: From 1931 to the present day. There are still some nations in Latin America that are under tacit Spanish colonialism. This last phase analysis is not included in this saga.

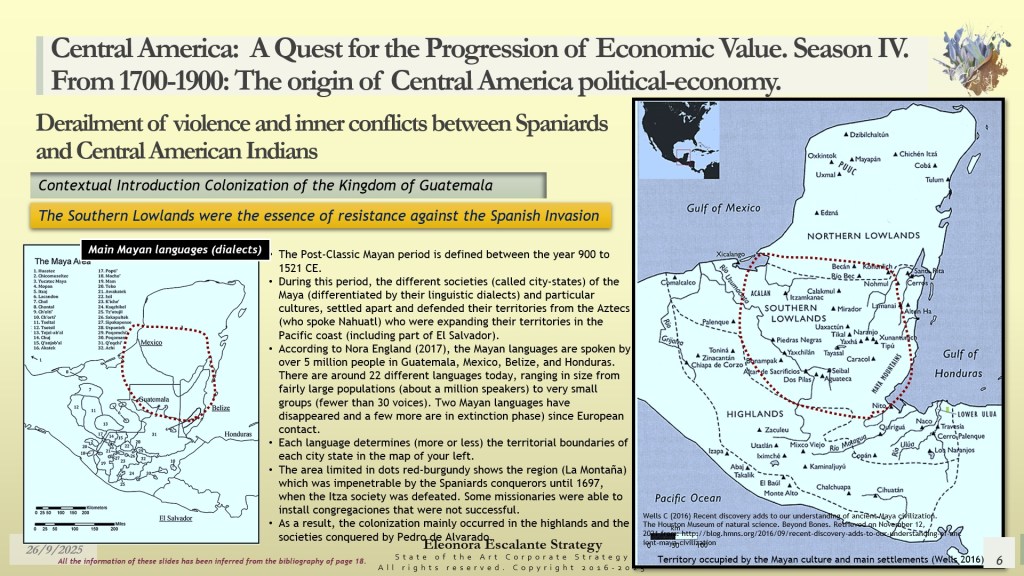

Our episode has limited our analysis to the Native Indigenous societies of the Northern part of Central America, simply because demographically, economically, and culturally, they all together represented the highest developed civilization, in comparison to the tribes located in Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The Mayan societies were positioned in what today is the Northern Triangle (Chiapas-Soconusco, Yucatán, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras), however, keep in mind that the southeastern part, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, were also part of the Audiencia de los Confines (later called Audiencia de Guatemala). We use the term Kingdom of Guatemala as an alternative expression of this Audiencia.

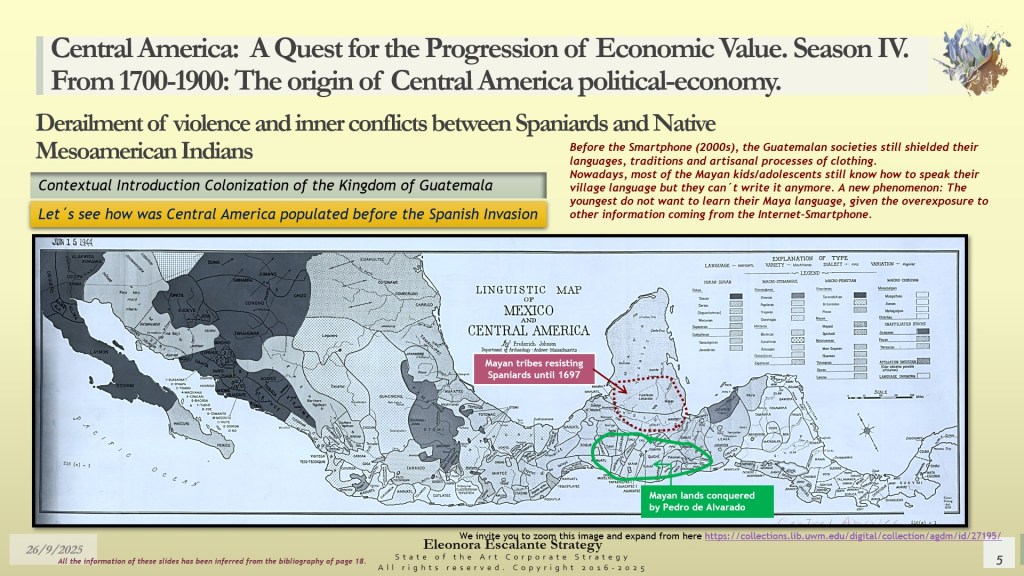

Linguistic Map of Central America. Slides 5-6.

We start our analysis (slides 5 and 6) by showing you how the linguistic map of Central America was. This snapshot is right before the Conquest. The interesting feature of this map (slide 5) is that it demonstrates that Central America was not a uniform region; it was fragmented, and it was linguistically and culturally atomized. Furthermore, the indigenous communities were not a cluster of warriors against the Spaniards; they had territorial conflicts among themselves. We have outlined this reality as it has been informed by historians: Pedro de Alvarado only conquered the Mayan highlands, but not the Southern Lowlands (La Montaña remained untouchable until 1697). Cristóbal de Olid took Honduras by sea first, and then Cortés reaffirmed his presence by consolidating his control with the establishment of Puerto Natividad. In parallel, Pedro Arias Dávila conquered Panamá first. Nicaragua was then being conquered by Francisco Hernández de Córdova. In terms of strategic growth, where the acquisition of the land by conquest was the way to go, the conquest of Central America was not uniform. The Conquistadores entered from the North (Cortés team) and from the southeast (Pedrarias team), and they met in juxtaposition in Honduras, the Fonseca Gulf, and some parts of El Salvador.

This fact is philosophically relevant. One thing was to kill the Indigenous leaders and celebrate a victory of an initial possession of the land by conquest. Another thing was to be accepted as the new lords of these lands by the native pre-Hispanics. We have observed a consistent Indigenous resistance throughout the region. For example, in 1561, Conquistador Juan de Cavallón was the one who truly attained possession of this land, while Juan Vásquez de Coronado took over as the governor of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, establishing Cartago in 1564. There are testimonies of the Castilla de Oro (Costa Rica), which explain the high level of violence and murder against the indigenous people during the conquest and colonization process. We wonder how it is possible that some of them survived after such massacres. Just a miracle of God!. Eight Indigenous peoples live there now: the Huetar, Maleku, Bribri, Cabécar, Brunka, Ngäbe, Bröran, and Chorotega, constituting around 2.4% of the total population (2024).

In the Northern Triangle of the Kingdom of Guatemala, the establishment of colonies after the conquest was not typically military. It was religious. The Catholic friars established churches and monasteries all over. The Catholic friars mapped cartographically, inventoried the native societies per linguistic and cultural factors, shaped census of populations, built churches and established new connectivity routes, and, lastly, they designed the territorial organization of the land. They defined the encomienda areas, and many times, they expanded them under their patronage. Some Catholic priests were able to build a piety and good reputation among certain encomiendas and repartimientos, so they were also the only ones who could enter certain zones (as the Montaña villages of Guatemala Southern Lowlands, for example), without the risk of being punished by the resentful fugitive Native Mayans. Slide 6 shows you the La Montaña zone, which was the refuge, the sanctuary for the Mayans until 1697.

How the Spaniards colonized the Mayan Indigenous communities. Slide 7.

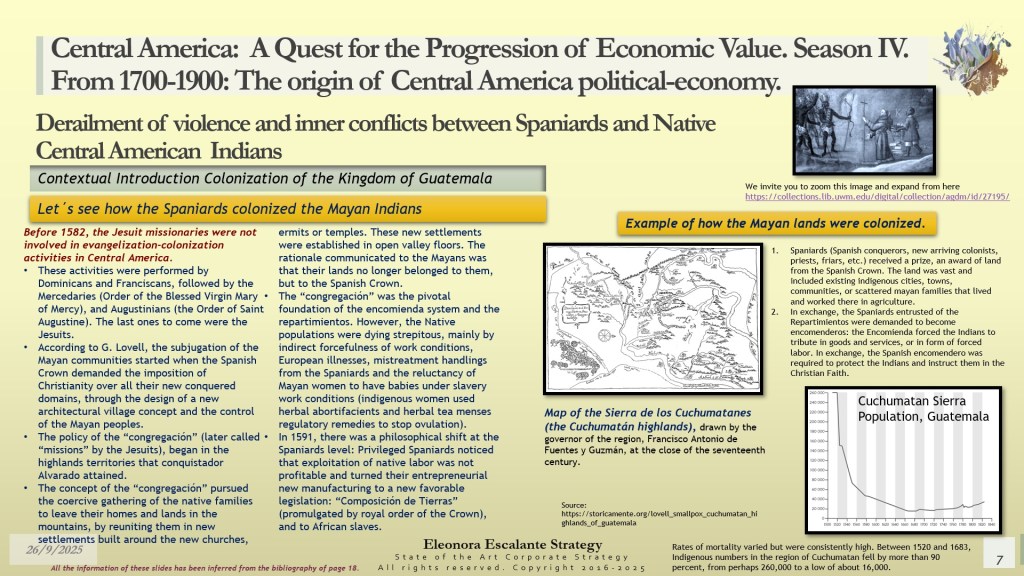

We have studied the case of the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes repartimiento (later called Corregimiento of Cuchumatanes Highlands). The population of this village almost disappeared. The causes: forceful work conditions, psychological unhappiness and despair, the combination of the transmission of all infectious European illnesses, mistreatment and handling of the communities, and the reluctance of women to procreate in slavery conditions. The encomienda was a factual entity. It was not invented in America. It was imported from the Iberian Peninsula (the encomienda was the historic solution of the Castile-Leon Kingdoms used during the Reconquista period to subjugate the Muslims). Of course, it was conducted and utilized again to subdue the Indigenous villages by the Conquistadores (let´s remember that all Conquistadores were SWAT mercenary fellows from the top orders at the service of the Spanish King).

The importance of understanding the encomienda system. Slides 8 to 10.

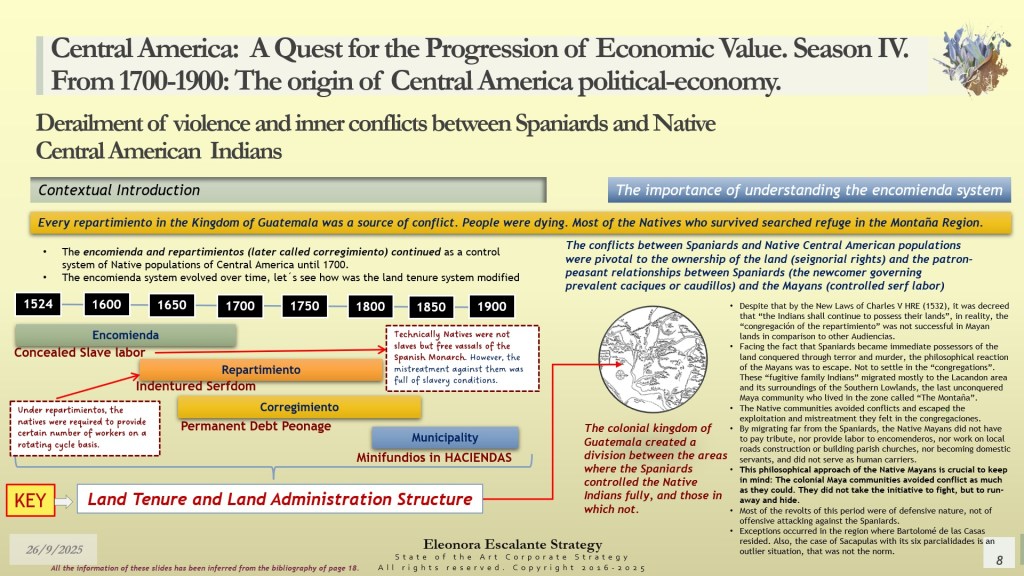

Now we have landed in the first phase of colonization. The study of the evolution of the encomienda system into a municipality in Spanish America is also of critical relevance. Each Audiencia had its own particularities. As an economist or historian, it is imperative to classify the whereabouts of the encomienda systems according to the location in Latin America. The conceptual definition of encomienda is the same, but the application of how they were implemented is different. The encomienda system has still not been analyzed from the corporate strategy perspective, hand in hand with historians, and this is a huge hole that requires our attention. I am convinced that this is a pending domain of study that has been taken lightly by economists. Particularly, those who are working to help Latin America reach the plateau of development. Our following discovery is just an abstraction that needs to be confirmed. Let´s deduce. There has been a process of evolution of the tenure of the land in Latin America. As of the conquest, the encomienda was the kick-off point. See slide 8, please. We have sketched a general process of land tenure-indigenous labour.

- The process began with the encomienda, a form of concealed slave labor of the Natives without legal rights to the property.

- The repartimiento-indentured serfdom: indigenous contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years.

- Later, by the 1700s, the next step was the corregimiento-permanent debt peonage.

- After the Independence and the failure of the Federal Republic of Central America (1850s), the land was no longer owned by the king of Spain, but by the latifundistas or Hacienda owners (mostly creoles). This last model triggered the mini-fundios of the Indigenous natives, who worked all their lives in exchange for a piece of land for their subsistence agriculture. The mini-fundios occurred inside the big haciendas of the hacendados or patronos. It is during this phase that the descendants of the Native-Indians were able to sign a property contract under the ID of their respective Central American nation.

Please note: the Indigenous peoples were not considered citizens of the Kingdom of Spain. Never. Until after the Independence, they got their Identity Cédula as citizens of their respective local nation, but never from Spain. They were free subjects to the King of Spain; they represented cheap labor, but without an ID (cédula de identidad). For 300 years, they were nothing by law. They had no rights, no obligations, no possibilities of buy-sell property, and no system that could protect them.

The encomienda of the native pre-Hispanic populations is the direct cause of land inequality in the region. It is the foundation of it. According to several meaningful studies of several United Nations organizations, the Northern Triangle of Central America holds a Gini coefficient for land distribution of 0.81. See slide 9, please. This indicator has a range between 0 and 1. The higher the coefficient, the higher the inequality. Illustrating it simply: when the king of Spain was the absolute owner of all the land (as a productive asset) of Spanish America, the Gini coefficient was 1.0. In 2016, a Gini Coefficient for land distribution of 0.81 tells us that 19% of the population is the owner of all the land in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, while the remaining 81% of the population are not landowners, or do not own land. Look below at a simple illustration that might help to understand this concept. It is impossible to reach total equality scenarios because individuals differentiate themselves by skills and experience, but a range between 0.25 and 0.40 is more than enough. For an idea of the GINI Coefficient concept applied to the “Income” of some OECD countries, Denmark holds a coefficient of 0.27, the USA with 0.396, and Switzerland with 0.31 (all data from 2022). See: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1461858/gini-index-oecd-countries/

The concept of Prestanombre. Slide 10.

This slide holds the most important message of our episode. The notion of “prestanombre” is the figure that was used over time to transfer titles of property from the king of Spain to the criollos or Spanish peninsulares who were “rewarded” with land in Central America. Legally, the land was owned by them through a “prestanombre” scheme. A “prestanombre” is a holder of land tenure, in which he appears as the buyer of it, merely acting as a “false face” to the authorities. The prestanombre did not pay for the asset, but he was granted the utilization of his name as the proprietor of the land, facing the law, while the real land proprietor continued to be the Royal Spanish Crown or a member of the Royal family. After the Independence, when the Spanish Bourbons lost the sovereign possessions of Spanish America, we suggest that many of the new Criollos owners of the land acted as “prestanombres” for the monarchy or high authority members of the Audiencias. In México, the vastest haciendas might have been under prestanombre contracts too. On the other hand, as I have mentioned above, in the kingdom of Guatemala, until the 1850s, no native indigenous family was able to have land. They were not considered citizens at all.

Indian defenders. Slides 11 and 12.

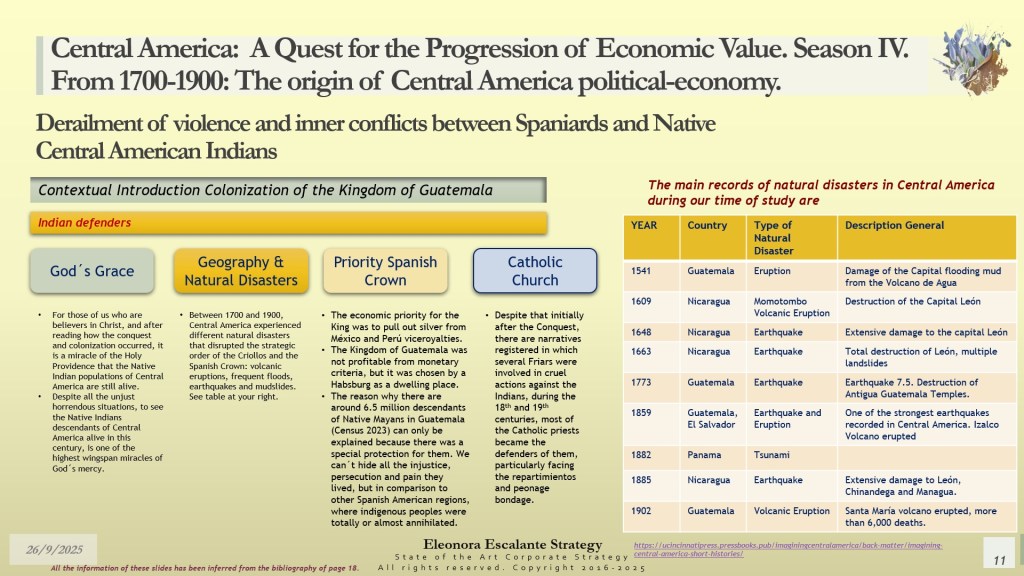

We have nailed that the native pre-Hispanic populations had direct and indirect protectors. The first and greatest of all is God. The miracle of God´s presence was real and genuine. That region of “La Montaña” and certain villages of the highlands saved hundreds of men from perishing under the violence of the first wave of conquistadores and their descendants. We suggest (according to our hypotheses) that they were not touched at “The Montaña” because there was a Habsburg member, descendant from Philip I and Charles V HRE, who kept them alive there, in that piece of land. The rest of the Native tribes of the Pacific coast of Costa Rica and Panama almost disappeared without a trace. The second defender of the Indigenous was the Geographic factors and Natural Disasters. The Natives were shut off from view because the territory was highly mountainous, and the powerful rivers, rainforests, and lakes made it possible. Additionally, the earthquakes stopped the advancement of the newcomers from Castile, León, and other places of the Iberian Peninsula. Antigua Guatemala suffered an 18th century of innumerable land tremors, while the 1773 earthquake destroyed all the temples’ splendor. This earthquake was so potent that it changed the strategy of the Habsburgs for the long term. We have discerned that a line of them emigrated to South America, to the places where the Jesuits were expelled from their missions (Paraguay and Argentina). The third defender was a team of some members or nobles around the Spanish Crown in the Peninsula who belonged to the original plan of Charles V Habsburg for Spanish America. These members were acting as a dam, fulfilling in secret the will of the resident Habsburgs in Chiapas-Soconusco and Guatemala. They were acting like spies to the new king’s administration. And finally, we have added the fourth defender, the Catholic Church. Read slide 12, please. The labor of the Catholic Church was to convert all the native indigenous to Christianity and defend their human rights. Not all the testimonies about them are positive; however, the respect of the autochthonous populations towards them is still omnipresent to this day. Some priests sacrificed their lives for the Mayan peoples, while others did not take their mission to that level. But adding the benefits of their company and subtracting the harms and liabilities, the result is always positive, constructive, and progressive to the Catholic Church, an institution that sheltered them the most. Numerous Native Mayan lands under Catholic Congregations/Encomiendas (later corregimientos) were transferred to Criollos or Peninsulares private holders or “prestanombres” after the independence.

Chronology of Main Events Kingdom of Guatemala (1540-1860). Slides 13 to 15.

This chronology shows the main events of 300 years of history. I have framed in a burgundy box the most violent conflicts registered between Spaniards and Pre-Hispanic Native communities. It was surprising to me to not find so many. However, we can´t infer based on this list, because the conflict between them was permanent. The Indigenous were not citizens by law. They had no resources to survive but to offer their labor under cheap schemes. They were “free subjects to the king of Spain” acting as slaves, with a brand of “free-men”, but receiving the lowest wages, which were used to pay debt to their corregidores, Patronos, Hacendados, or the village store. Most of them have been mistreated for centuries. Always hiding. Always running to camouflage between the wild nature and the trees. The culture of the Natives of Central America was so shocked with terror from the Spaniards that it is not in their nature to attack, but only to defend themselves after so many disgraces. The descendants of the natives of Guatemala, Honduras, or El Salvador are currently the humble migrants to the United States. Always trying to find opportunities that were banned for them historically in their own soil. So, there has been institutional violence against their bare minimum human rights. The record of all the attempts of the Native Indians to rebel against the Spaniards is not the official numbers that we can find in several history books. It is above that level. It was the norm of their convivence. In consequence, for the time being, we only suggest that this hard work of finding the truth is only beginning. Nonetheless, now you can comprehend why today, the USA continues to attract the Central Americans, particularly if the labor for the agricultural workers of the former nations of the Kingdom of Guatemala is paid 1/10 of what they can earn per hour in the USA.

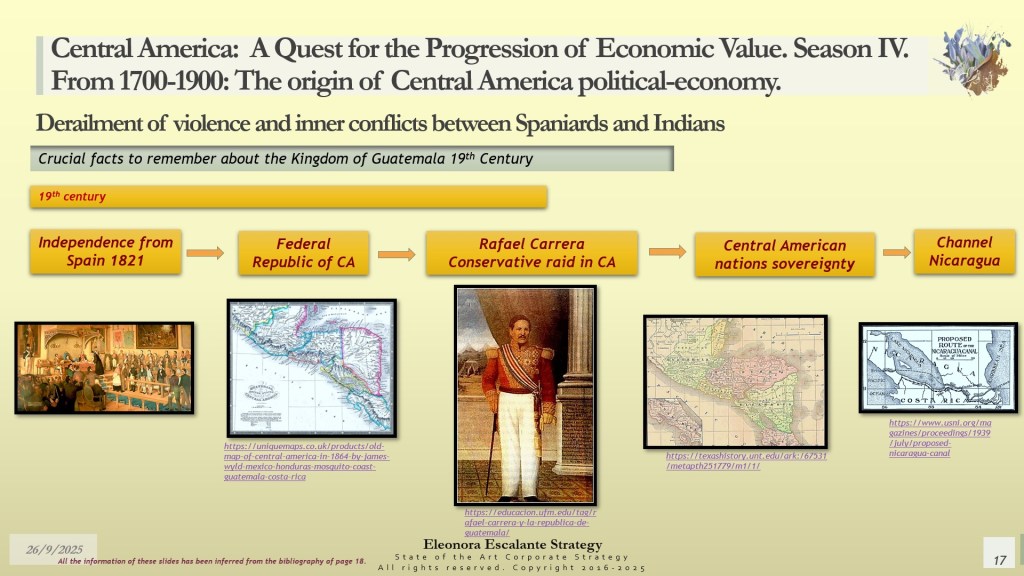

The chronology of main events will help us with the rest of the saga. Read it with careful attention. We have compared at least 5 books of good academic roots to prepare it. Slides 16 and 17 are the summary of this chronology.

To be continued…

Announcement.

Episode 2 offers an abstraction of what the true rationale was behind the violence and internal conflicts between Spaniards and native Mesoamerican populations after the conquest and during the colonization of their lands in Central America. We have presented a detailed introspection of the encomienda system as the main cause of the current land inequality tenure in all of Latin America. Our next episode is “Independence Bells (1821-23)”. See you again next week. Thank you for reading to us.

Musical Section.

During season IV of “Central America: A Quest for the Progression of Economic Value,” we will continue displaying prominent virtuosos who play the guitar beautifully. However, we will select younger interpreters who promise to become the new cohort of classical guitarists in the future.

For this episode 2, we have chosen a new lumière in the classical guitar, Raphaël Feuillâtre, from Djibouti, a country on the northeast coast of the Horn of Africa. Djibouti is situated on the Bab el Mandeb Strait, facing the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. He became internationally recognized after he won the prestigious Guitar Foundation of America competition in 2018 (USA). As of 2022, he is an exclusive artist with the label house Deutsche Grammophon. We invite you to visit his website for further exploration of his nascent career.

https://raphael-feuillatre.com/home. Enjoy!

Thank you for reading http://www.eleonoraescalantestrategy.com. It is a privilege to learn. Blessings.

Sources of reference and Bibliography utilized today. All are listed in the slide document. Additional material will be added when we upload the strategic reflections.

Disclaimer: Eleonora Escalante paints Illustrations in Watercolor. Other types of illustrations or videos (which are not mine) are used for educational purposes ONLY. All are used as Illustrative and non-commercial images. Utilized only informatively for the public good. Nevertheless, most of this blog’s pictures, images, and videos are not mine. Unless otherwise stated, I do not own any lovely photos or images