Central America: A Quest for the Progression of Economic Value. Season IV. Episode 12. The Cacao Pilot Scoop of Central America

Blessings for the new holiday season of 2025. Today´s masterclass is about the original nidus of chocolate, the kingdom of Guatemala. Chocolate, as we all know it, is made from cacao beans. And the cacao beans were found by Europeans for the first time in 1502, during the 4th voyage of Christopher Columbus to America. The Spanish Conquistadores discovered that cacao was precious to the Native Populations of

Middle America, not just because of its medical and general properties, but also because it was the medium of currency for transactions at that time.

Our agenda for today will be developed in 5 themes:

- Cacao 101

- Why was cacao so precious?

- Mapping cacao production 16th – 17th centuries

- The scoop on the move: Horizontal growth trajectory 18th-19th centuries

- Consumption patterns driving the demand for cacao.

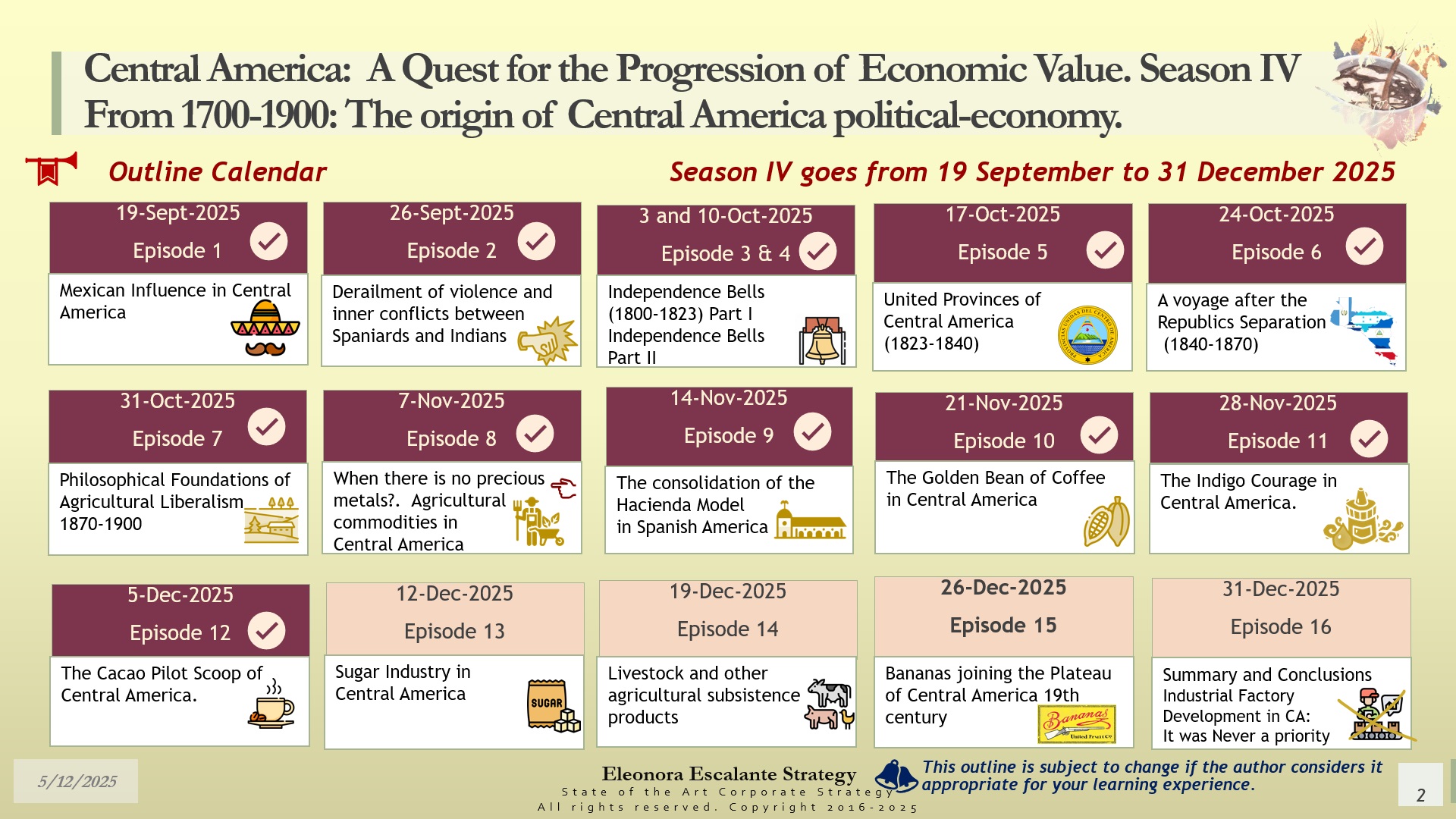

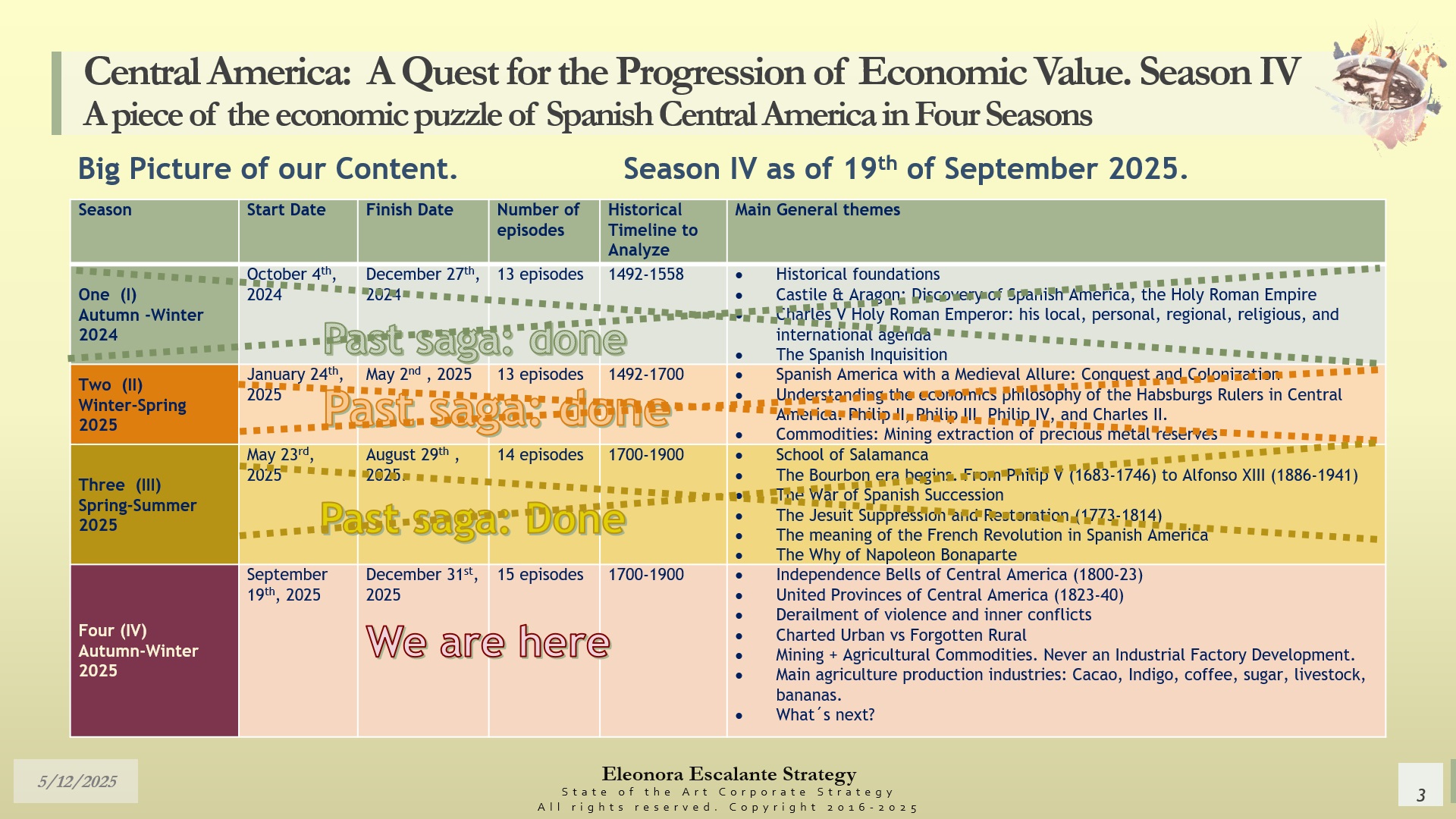

As it is our convention, we are providing today the general strategic framework in the following slides. This material is the foundation for your class. We encourage our readers to download it and print it. Make sure that you write your doubts and notes on each slide. We also insist on continuing to search for additional complementary information by following the URL links of our Bibliography located on slides 22 and 23 of the next document. Feel free to pass our material to your friends, colleagues, bosses, and professors for further discussion.

We request that you return next Monday, December 8th, to read our additional strategic reflections on this chapter.

We encourage our readers to familiarize themselves with our Friday master class by reviewing the slides over the weekend. We expect you to create ideas that may or may not be strategic reflections. Every Monday, we upload our strategic inferences below. These will appear in the next paragraph. Only then will you be able to compare your own reflections with our introspection.

Additional strategic reflections on this episode. These will appear in the section below on Monday, December 8th, 2025.

Strategic Reflections of today´s chapter: Central America: A quest for the progression of economic value. Season VI. Episode 13. The Cacao Pilot Scoop of Central America.

Cacao 101. Slides 5 to 10.

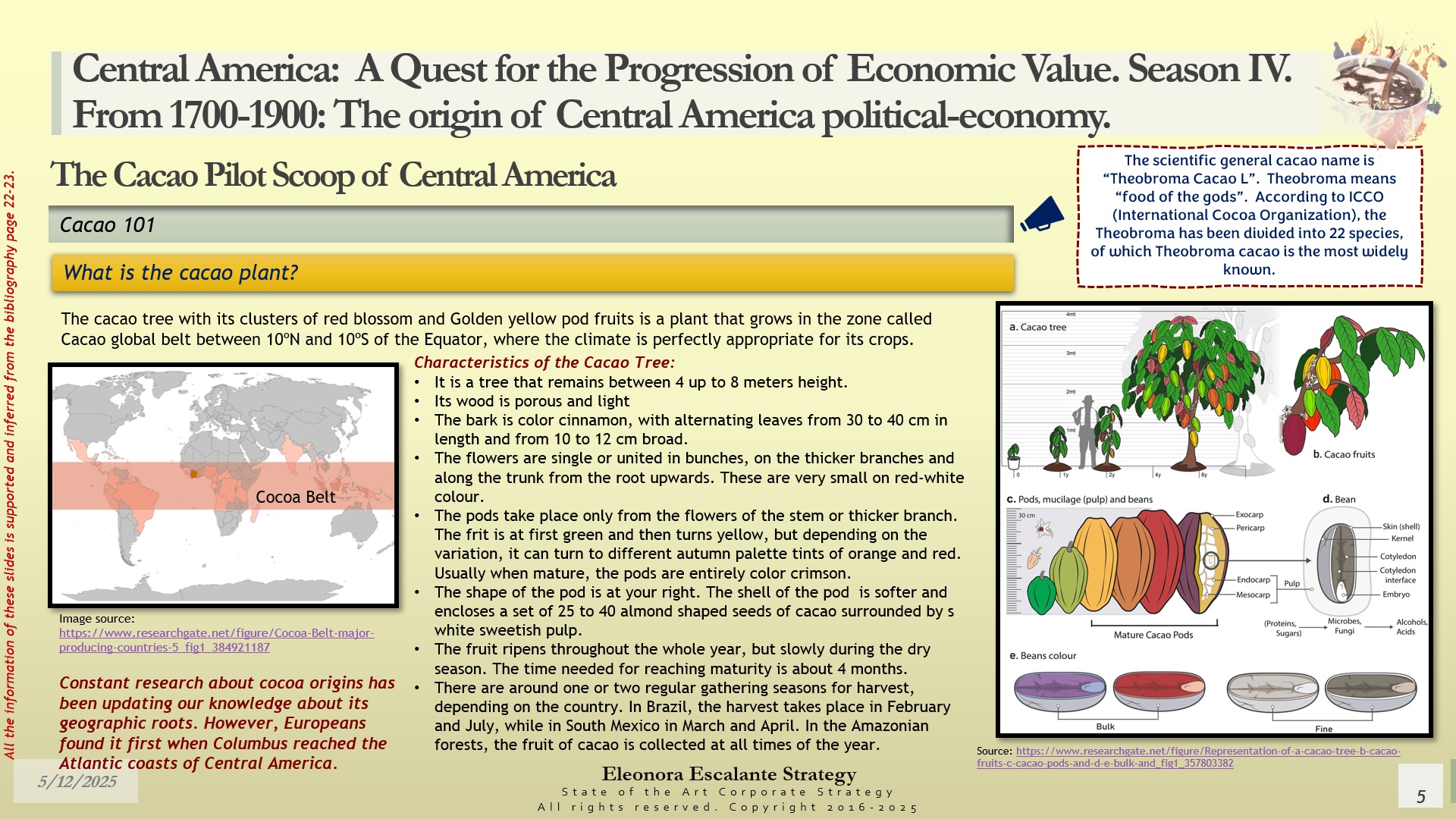

We kick off our material with a general description of the Theobroma cacao, the scientific name of the Cacao plant. See slide 5. The importance of this slide is to describe the plant we are talking about, including its form and main characteristics. The cacao pods were a treasure for the Mesoamerican inhabitants before the Conquest, and these only grow in specific climate conditions, in the region called the Cacao Global Belt. The cacao orchards are delicate to grow. They require attention and perfect climate conditions to thrive.

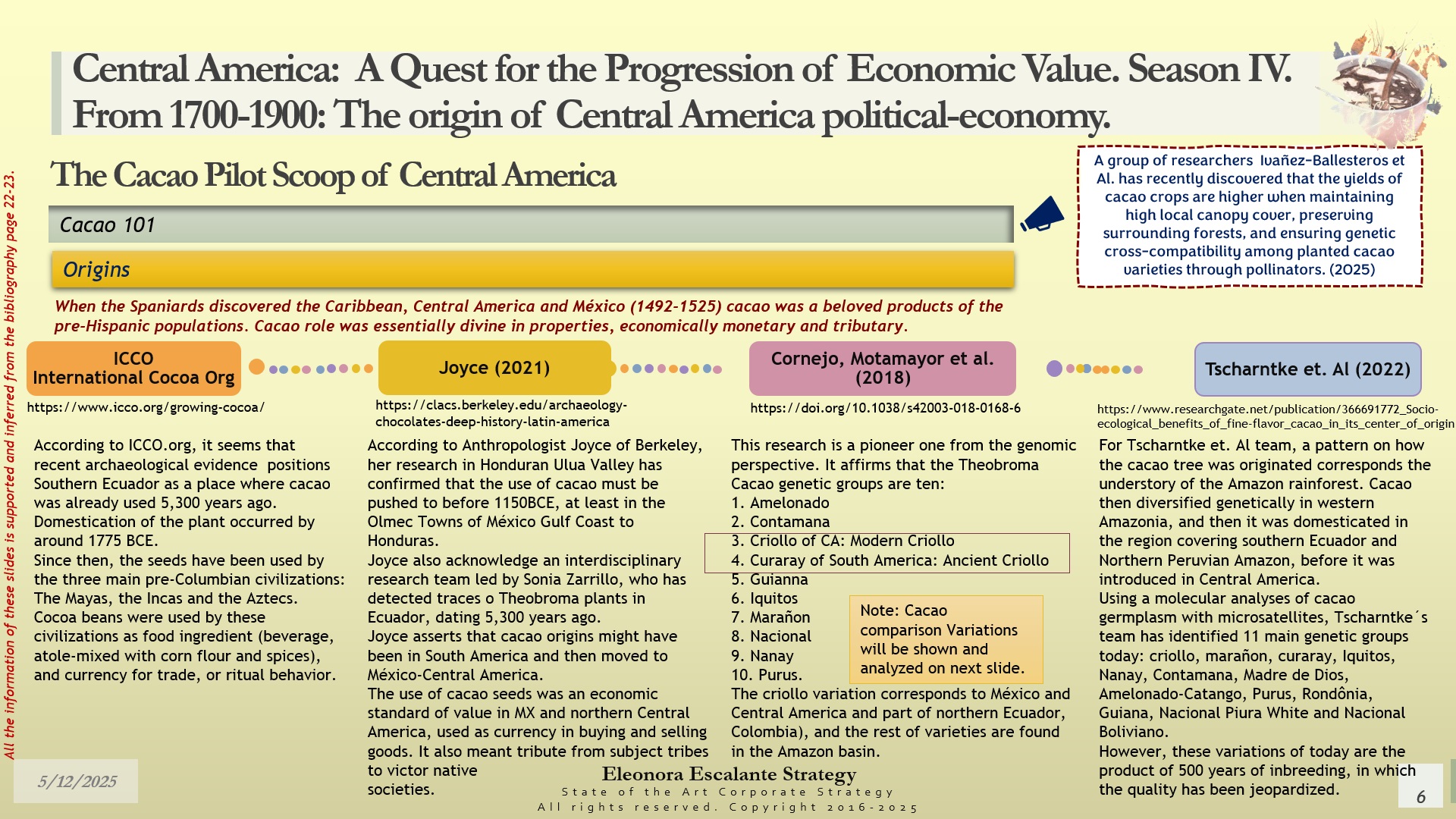

The origins of the cacao plant are not yet clear. For decades, the scientific community thought that the first archaeological traces were established in the Aztec and Mayan lands. However, recently, there has been pioneering research using modern genetic technologies that has discovered older cacao traces in Southern Ecuador (5,300 years ago). I have found some researchers who affirm there are 10 genetic groups, while others consider 11 variants. See Slide 6. In any case, the first existence of cacao is in America. The pollinators have done their natural mess, and even the International Cocoa Organization diverges on the recent classifications of the plant genetic variations. Currently, many specialists are worried about the reduction of cacao bean yields because not all the cacao plantations are kept with high local canopy covers and are not preserving the surrounding forests much needed for the pollinators.

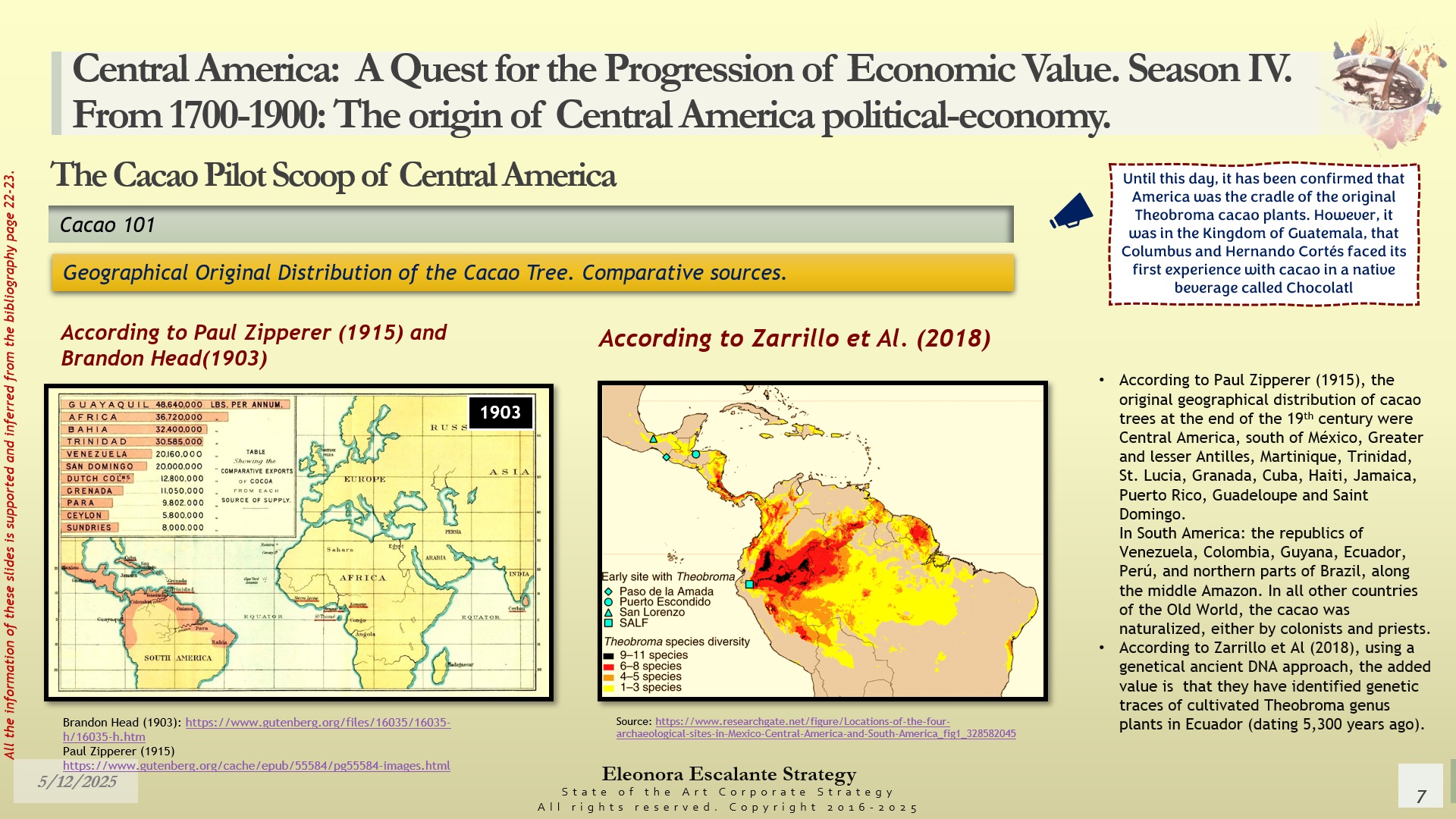

We visited two sources of research when we landed to study the geographical original distribution of the cacao tree. One is from the German Paul Zipperer (1915) and Brandon Head (1903), and a recent one from Zarrillo et Al (2018). Both studies agree that the cradle of the Theobroma cacao plants was probably around the Ecuador/Amazonian area. The authors of the beginning of the 20th century (Zipperer and Head) were guided by the main regions of production of it, naming Guayaquil (Ecuador) as its premier export country to Europe at that time. In comparison, 100 years later, Zarrillo et al (2018), have proven that it is in Ecuador where the first cacao genetic traces belong. See slide 7.

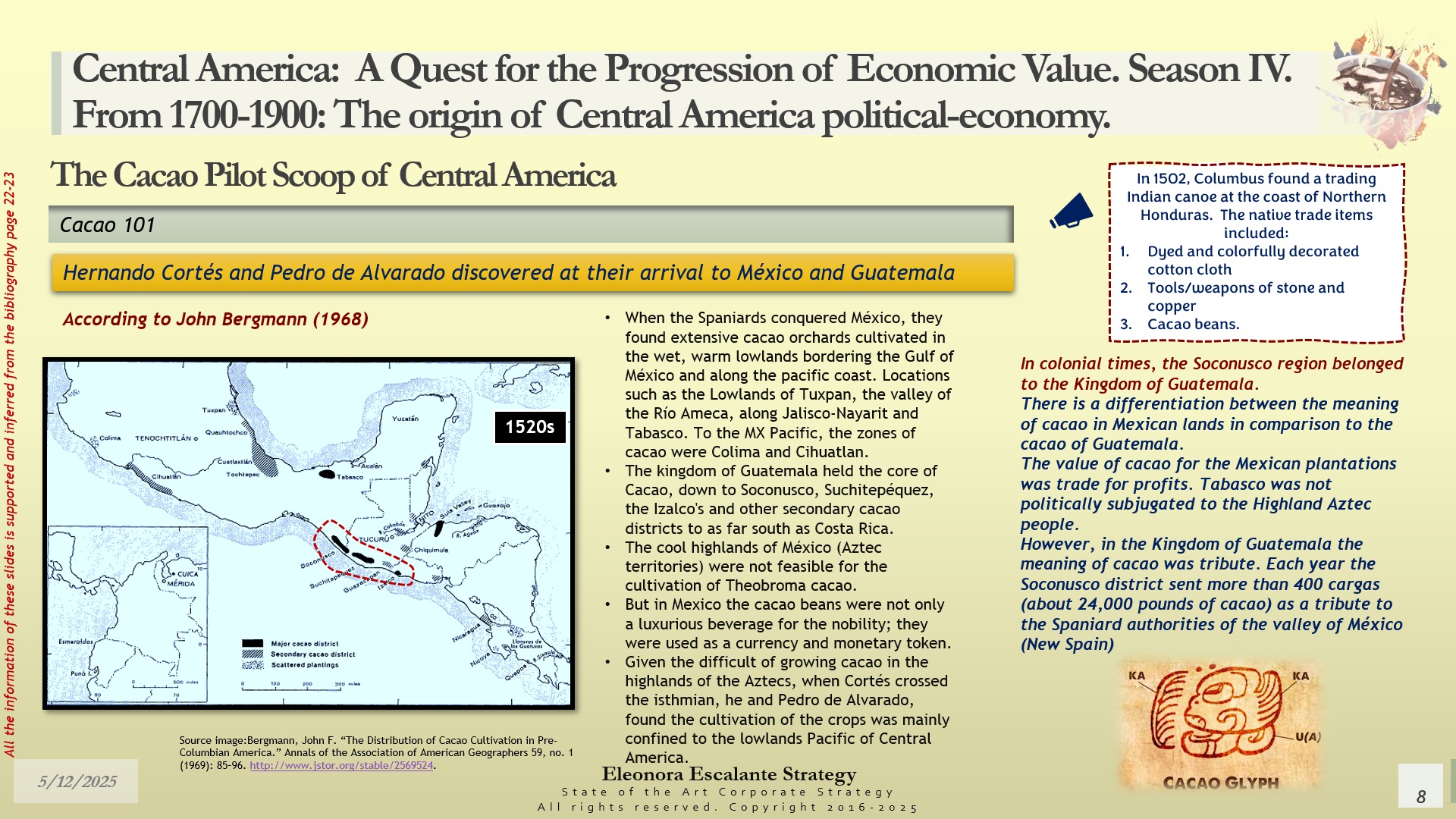

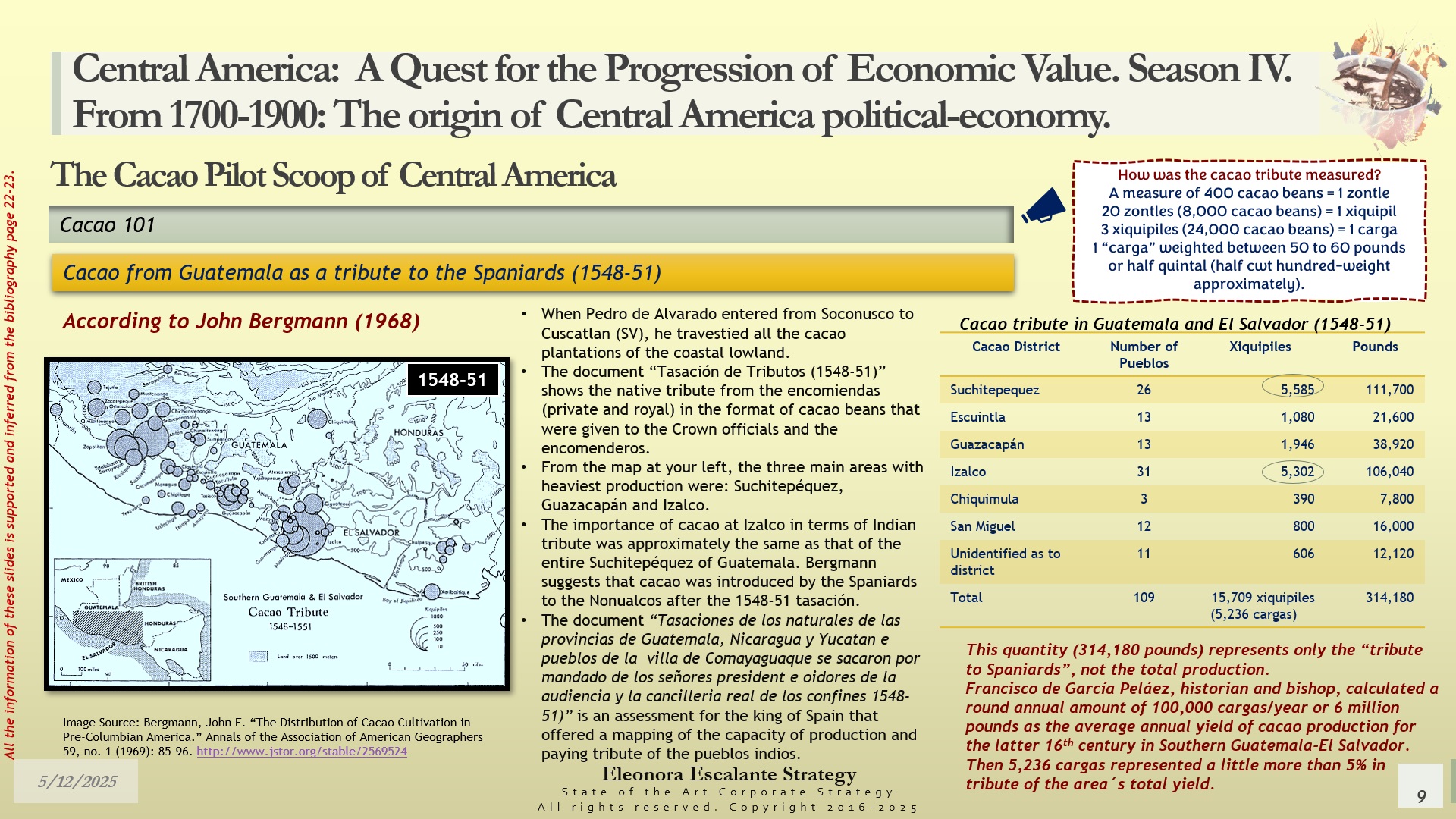

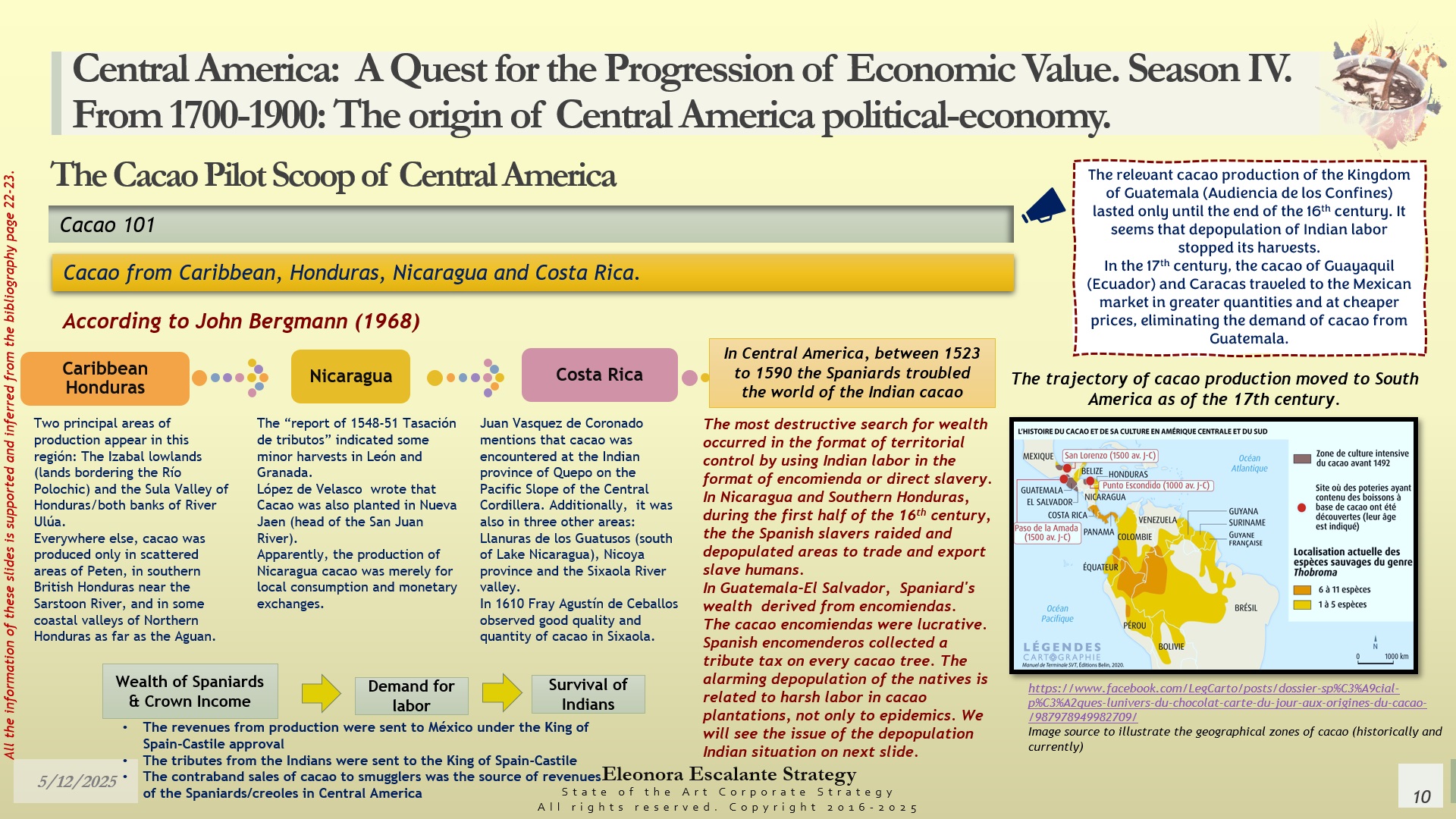

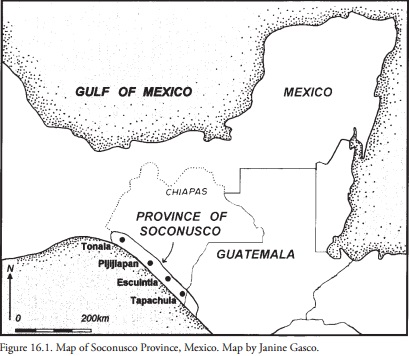

How did the Spanish conquistadores find the cacao plantations in America? From the first discoverer, Columbus, to Hernán Cortés and Pedro de Alvarado, they all encountered extensive cacao orchards cultivated by the Aztec and the Maya civilizations on both sides of the ocean borders (Pacific and Atlantic). However, according to researcher John Bergmann (1968), the core major cacao production districts were in Tabasco (MX), Soconusco (Chiapas), Suchitepéquez (GUA), Izalco (SV), and Sula Valley (Honduras). See slide 8. Regarding Central America, the region of Soconusco was suited for cacao cultivation. The patterns of the indigenous communities of the Soconusco (see map above) in relation to cacao planting were to keep the heavily forested environment the most. According to researcher Janine Gasco (1), cacao was planted the most in this territory between 1800-400 BC. However, by the time of the arrival of Hernando Cortés, the Soconusco natives were tributaries to the Aztecs, and the main utilization of cacao was to send it annually to the Aztecs. Additionally, the cacao was one type of tribute good (cultigens) that was used for domestic transactions. During the first quarter of the 16th century, the Soconusco population density was 7 people per km2, but during the entire colonial period, it was reduced to 1.5 people per km2. The mortality rates in all the cacao pueblos were as high as 95% or more during the first 60 years after the imposition of the Spanish colonial rule, and this impacted the cacao economy a lot, despite the requirements of the Spanish officers and encomenderos. In the Izalco region, the situation was not better than in Guatemala when it comes to the decrease in cacao workers. Between 1548-51, researcher Bergmann stated that there were 109 native pueblos from the Cacao District (see slide 9) paying 314,180 pounds of cacao as tribute to the Spaniards. These numbers are also confirmed by other sources, and by projection, we can infer that at least 6 million pounds was the average annual yield of cacao coming out of Southern Guatemala and El Salvador. This data source is from an analysis of cacao “taxation” which was officially studied and assessed by order of Charles V HRE (and the young Philip II Habsburg-Aviz). Moreover, slide 10 also shows a summary of the situation of cacao for the rest of the secondary cacao regions, the Sula Valley-Caribbean Honduras, the Nicaragua Nueva Jaén zone, and the Costa Rican Llanuras de los Guatusos. Since the Spaniards were also intertwined with the Portuguese, when the Portuguese began to export slaves for their sugar plantations in Brazil, it was quite normal for them to use the same business model of slavery within the Kingdom of Guatemala. The encomienda was slavery. And it was the award given by the Spaniard Crown to its staff in the kingdom of Guatemala. The core Cacao Plantations were already producing pods, and in consequence, the Spanish encomenderos only used the same established and existing tribute structure of cacao, but for them. Most of the cacao sales were traveling to México, and from there to Spain.

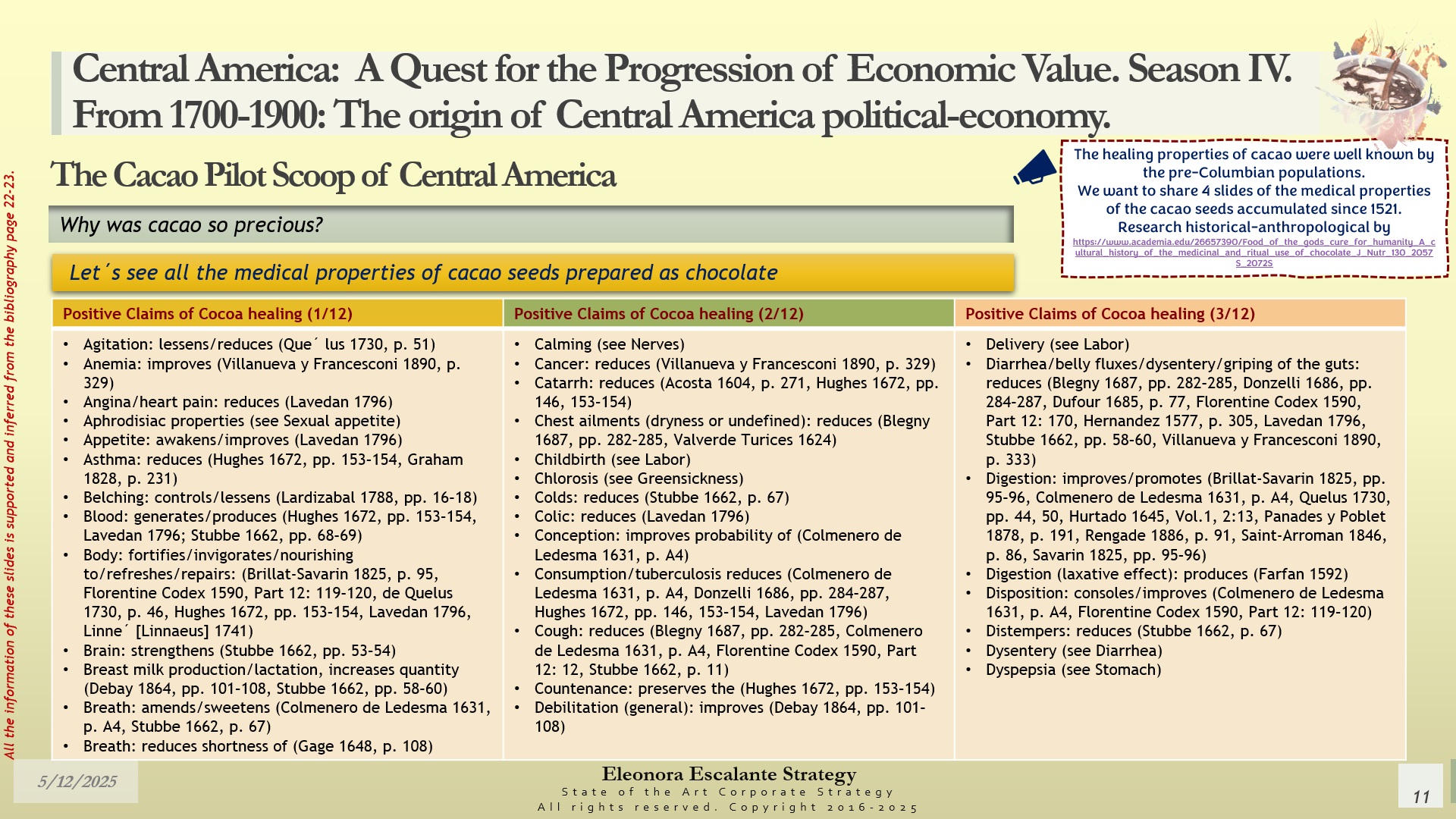

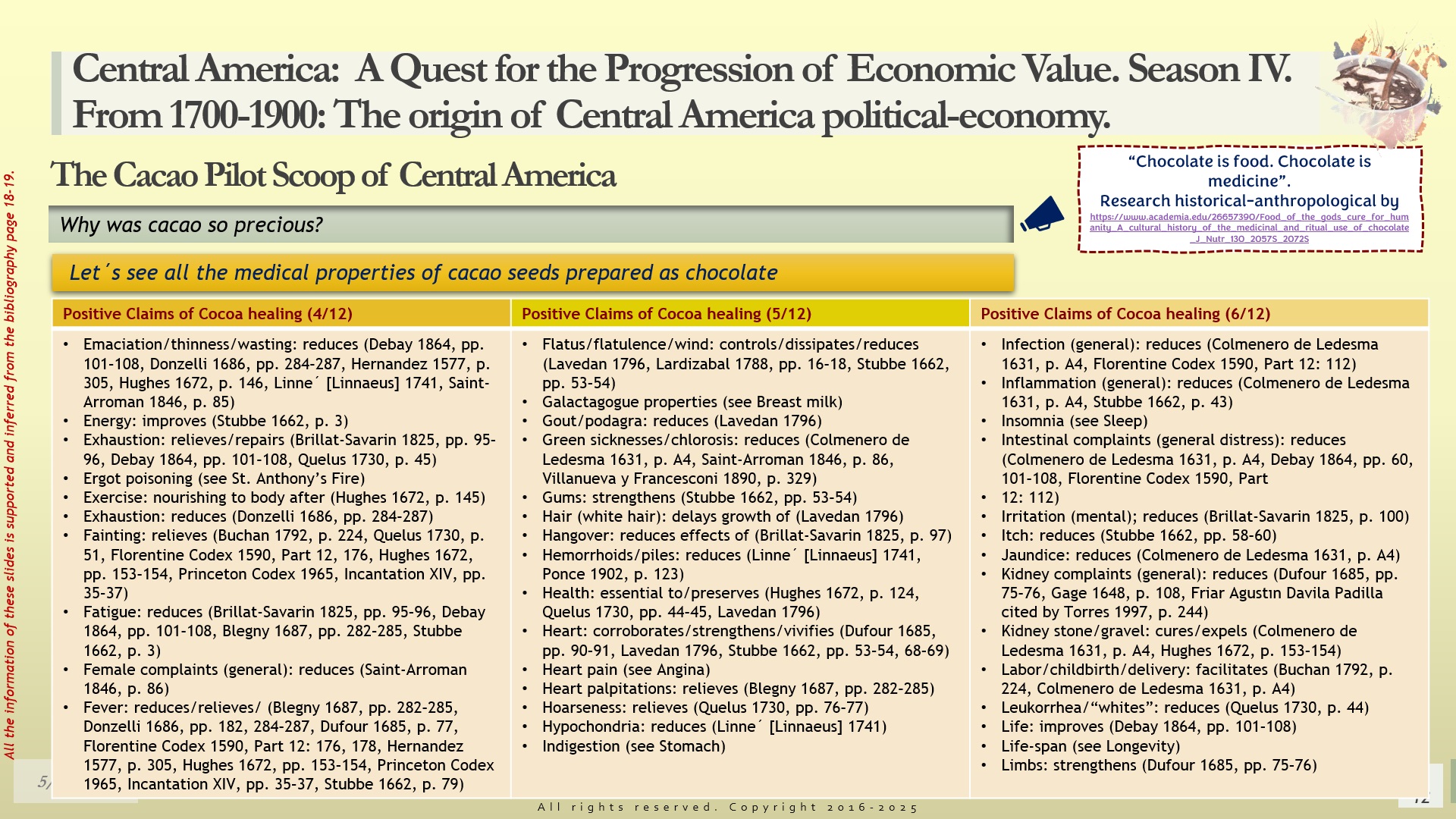

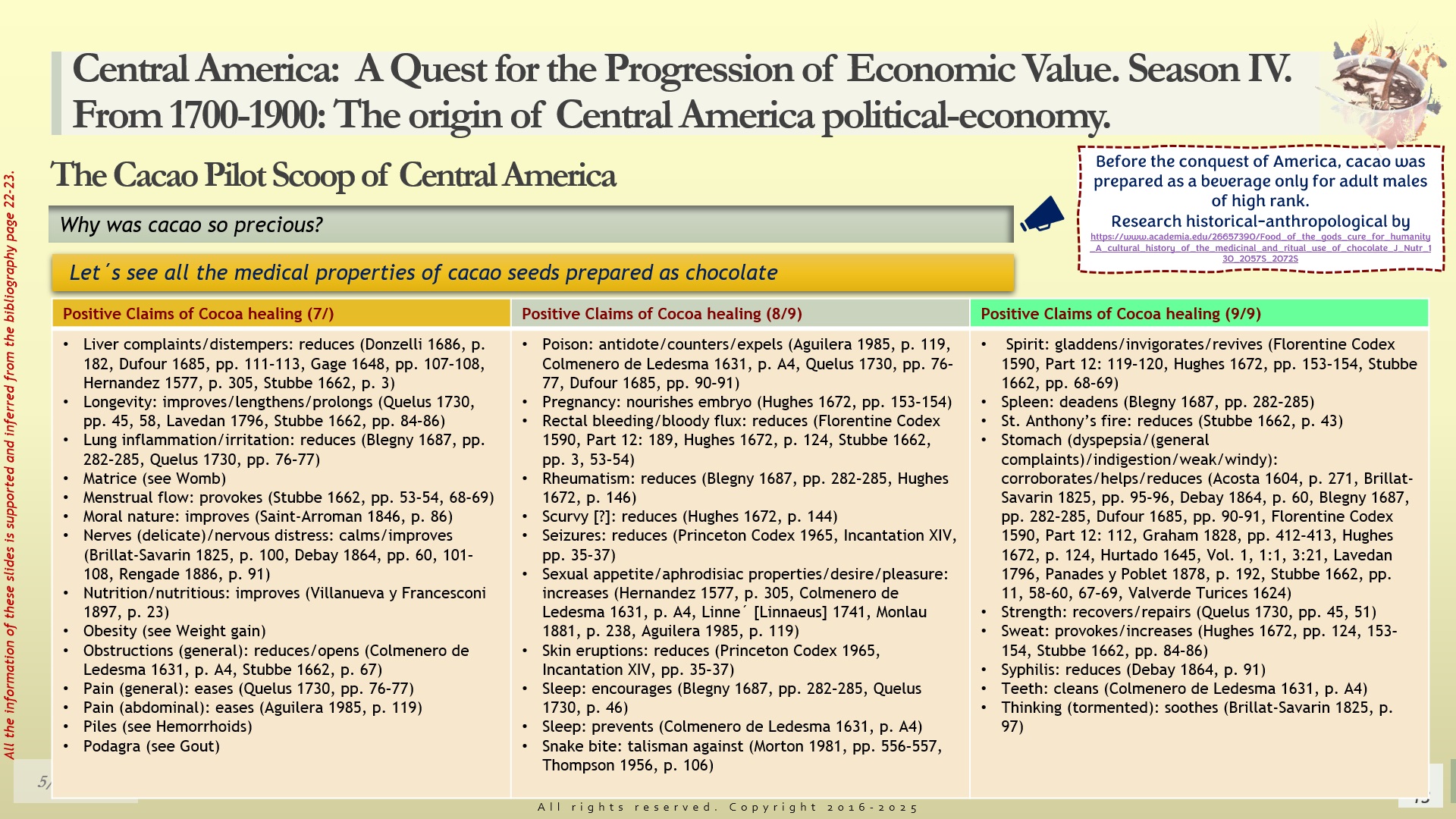

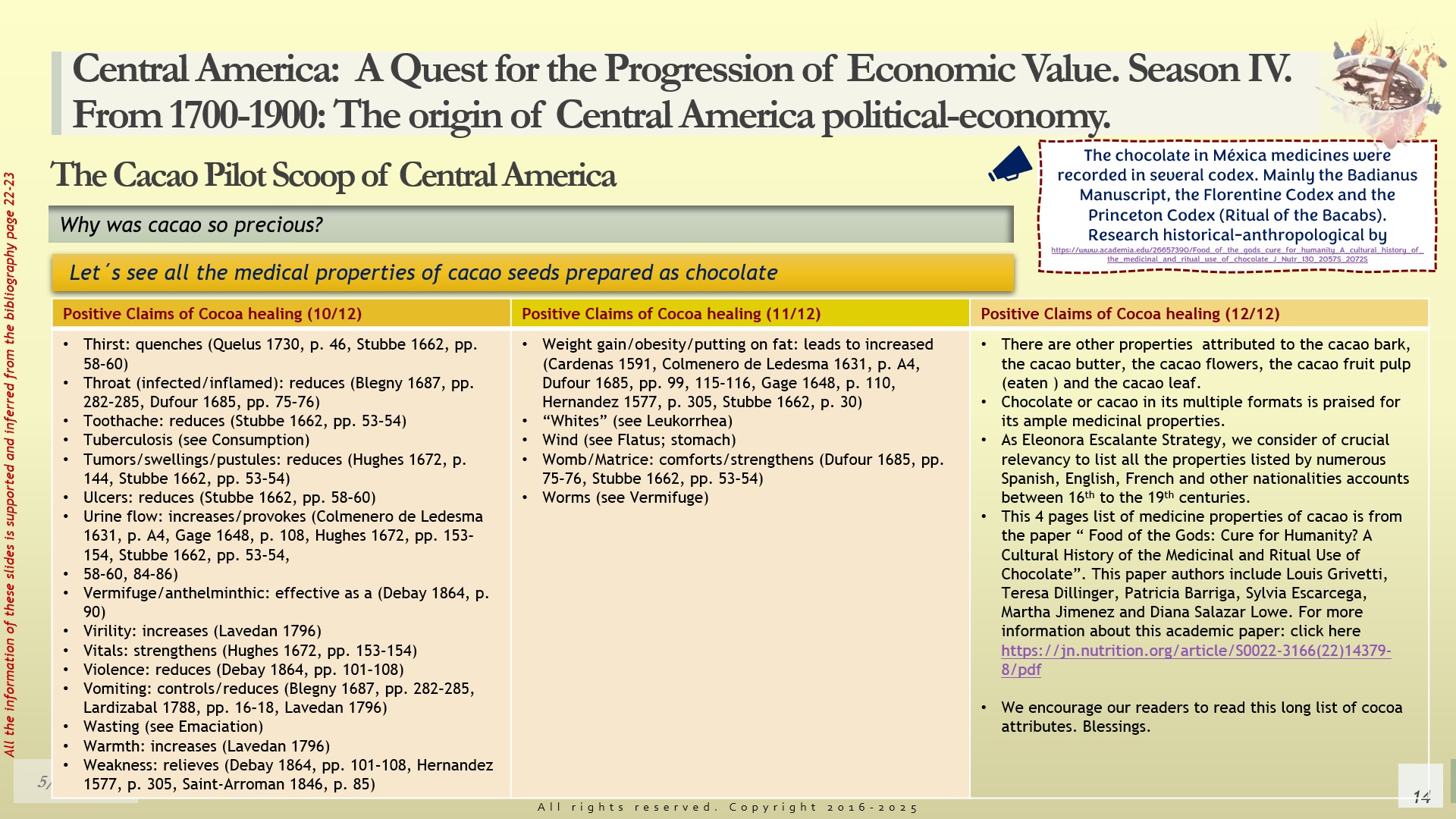

Why was cacao so precious? Slides 11 to 14.

We found an interesting academic paper from a team of researchers (2) who gathered a lengthy list of 126 positive claims of cocoa healing properties. The fascinating contribution of these nutrition historical detectives is that they have compiled the cacao restoring attributes based on ancient sources of knowledge, as the Native information registered in the Badianus Codex (1536), the Florentine Codex of Sahagún (1590), and the Princeton Codex (The Ritual of the Bacabs), discovered in 1914 in Yucatán. It also includes the cacao benefits described in European and New Spain documents and manuscripts of more than 35 sources (authors) between the 16th and 20th centuries. By comparing them, the authors have identified 3 consistent cacao curing advantages:

- “To treat emaciated patients to help them gain weight.

- To stimulate the nervous systems of apathetic, exhausted, or feeble patients,

- To improve digestion and treat stagnant or weak stomachs, stimulate the kidneys’ performance, and improve bowel function.

Other benefits include treatment for anemia, poor appetite, mental fatigue, poor breast milk production, tuberculosis, fever, reduced longevity, and poor sexual appetite or low virility.” In Europe, the fame of chocolate and its contagion to all the nobility was its aphrodisiac characteristics.

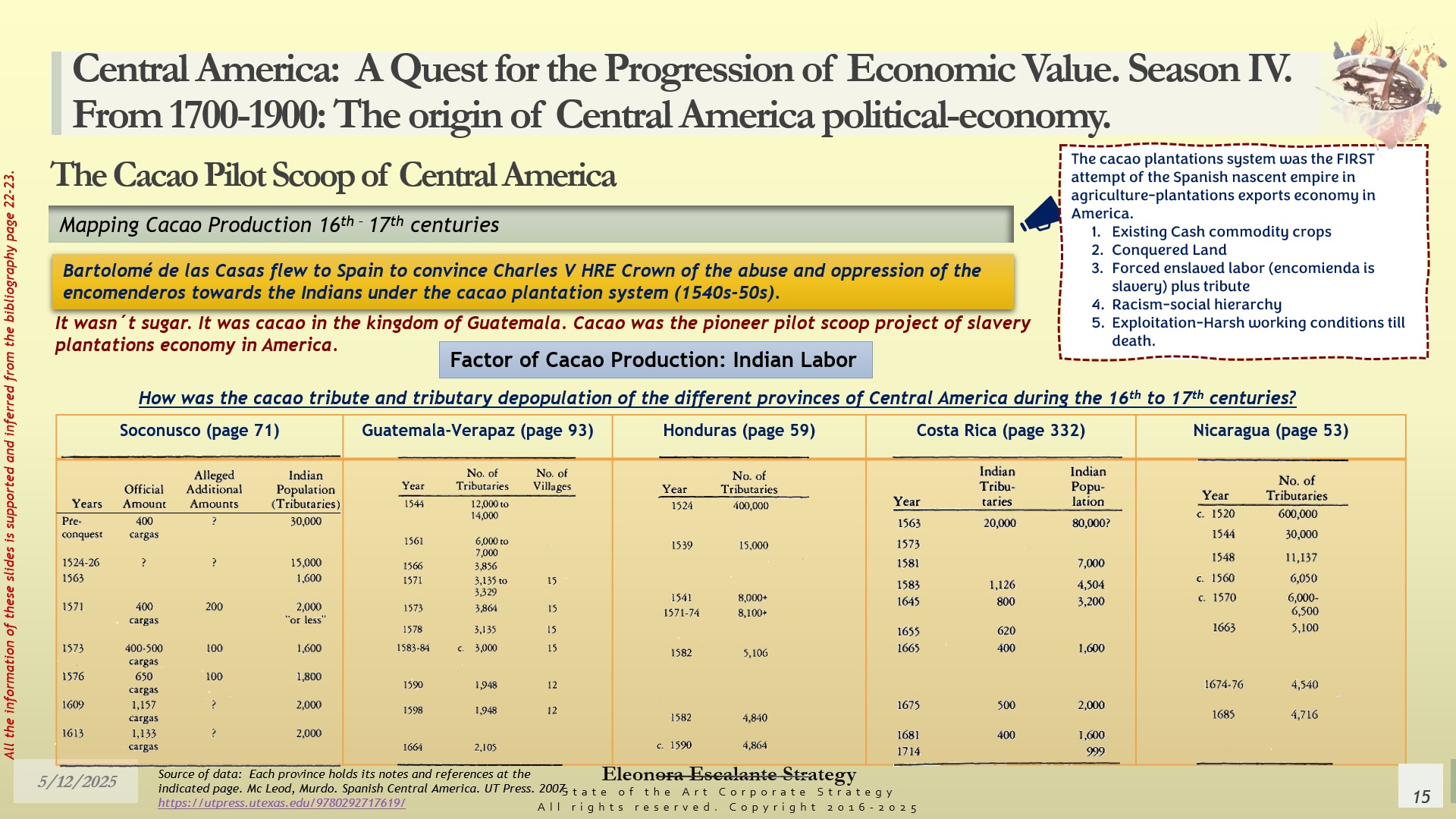

Mapping Cacao Production 16th-17th centuries (slides 15-16).

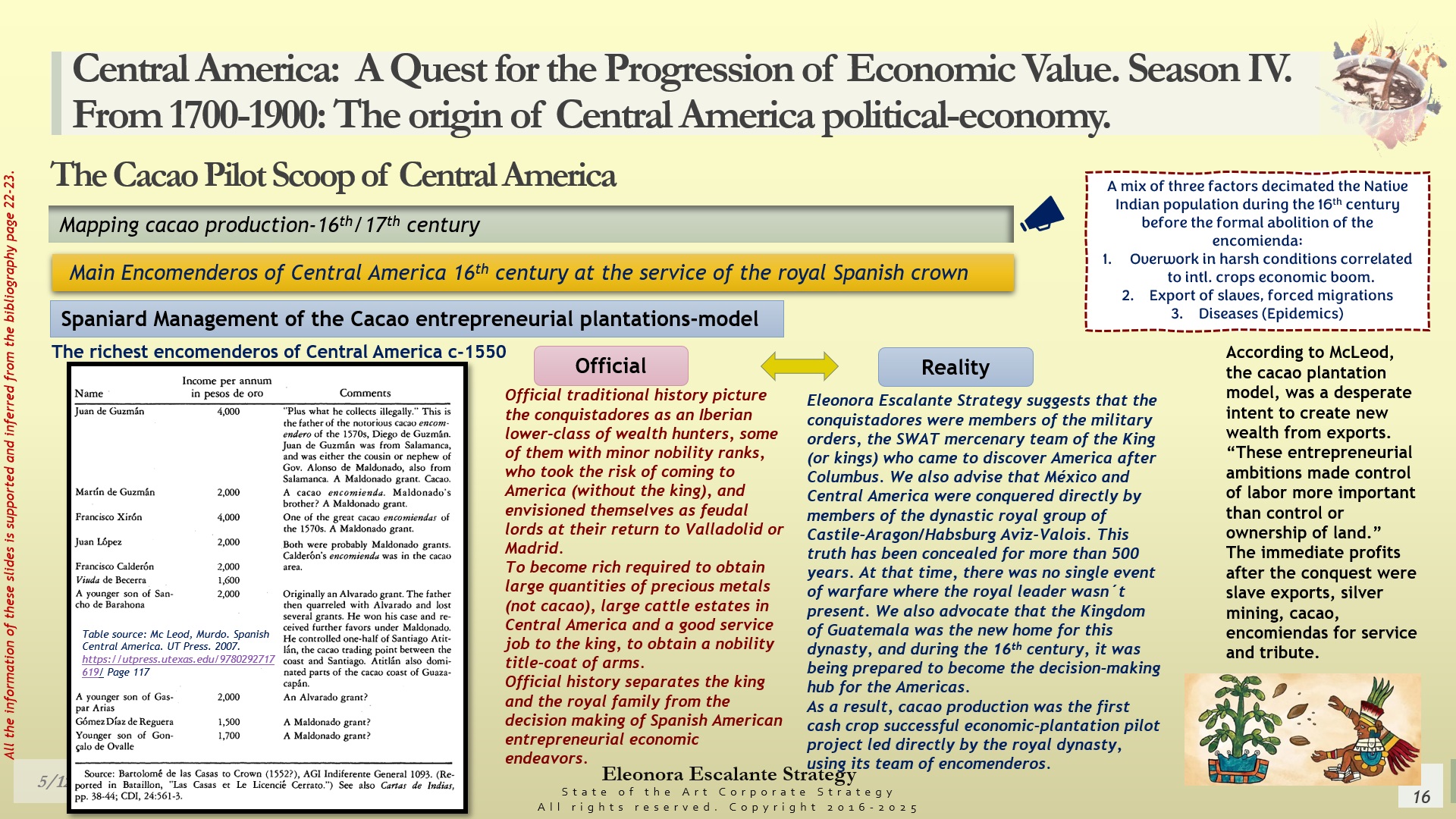

The initial slavery of the Indian Natives throughout all the Cacao plantation territories of the Kingdom of Guatemala was not because of sugar. It was cacao. It was under the first pioneer agriculture exports production of this commodity that the Indian labor was almost lost from the earth. Slide 15 shows us the patterns of depopulation of Indian tributaries from the main 5 provinces of the Audiencia de los Confines between 1520 and 1714. According to McLeod (see slide 15), we have calculated the reduction of the Indian tributaries’ population per province as follows:

| Province-Cocoa Region | Period of Analysis (Span Years) | Tributary depopulation (%) |

| Soconusco | 1524-1615 (91 years) | 93% |

| Guatemala-Verapaz | 1544-1664 (120 years) | 84% |

| Honduras | 1524-1590 (66 years) | 99% |

| Costa Rica | 1563-1714 (151 years) | 80% |

| Nicaragua | 1520-1685 (165 years) | 98% |

On average, the native pre-Hispanic tributary populations of the Kingdom of Guatemala (from Soconusco to Costa Rica) almost disappeared by 91% during a mean period of 119 years. This occurred mainly because of three reasons: (1) Overwork in harsh conditions correlated to cacao crops and some mines (in Honduras); (2) Forced migrations of the Natives; (3) Diseases or epidemics. All these factors together were determinants in the decline of the tributary Indian populations.

The Spaniard management of the Cacao-entrepreneurial plantations model has been described by MacLeod. By the year 1550, he had identified several encomenderos; the richest of all was Juan de Guzmán with 4,000 gold pesos per annum. See the table at slide 16. Let´s notice that the Spaniards replicated the same pattern of the Portuguese crown when it comes to the use of slavery in plantations. Additionally, we would like to recall that the Portuguese crown was part of the Habsburg family since the patriarch Maximilian Habsburg Aviz, then again, when Isabella Aviz married Charles V HRE. Additionally, Philip II Habsburg-Aviz held strong ties with Portugal when he married his niece María Aviz-Habsburg, and later when he succeeded the Portuguese throne in 1580.

Slide 16 shows why we must re-investigate how was the reality of colonial Central American domains. We are convinced that there are enough discrepancies in official history, which permit us to confirm that the kingdom of Guatemala was being prepared from the start as the new home for the Habsburg-Valois/Castile-Aragón descendants (including an Aviz side). The presence of Bartolomé de las Casas was not fortuity. The Hieronymites were part of the religious protection of Emperor Charles V, and they also hold the truth of what occurred during the 16th century in this region. There are traces of criollos’ last names linked to the House of Aviz of Portugal, while the British Tudor-Aragon, omnipresent in the Atlantic, means more than just smuggling.

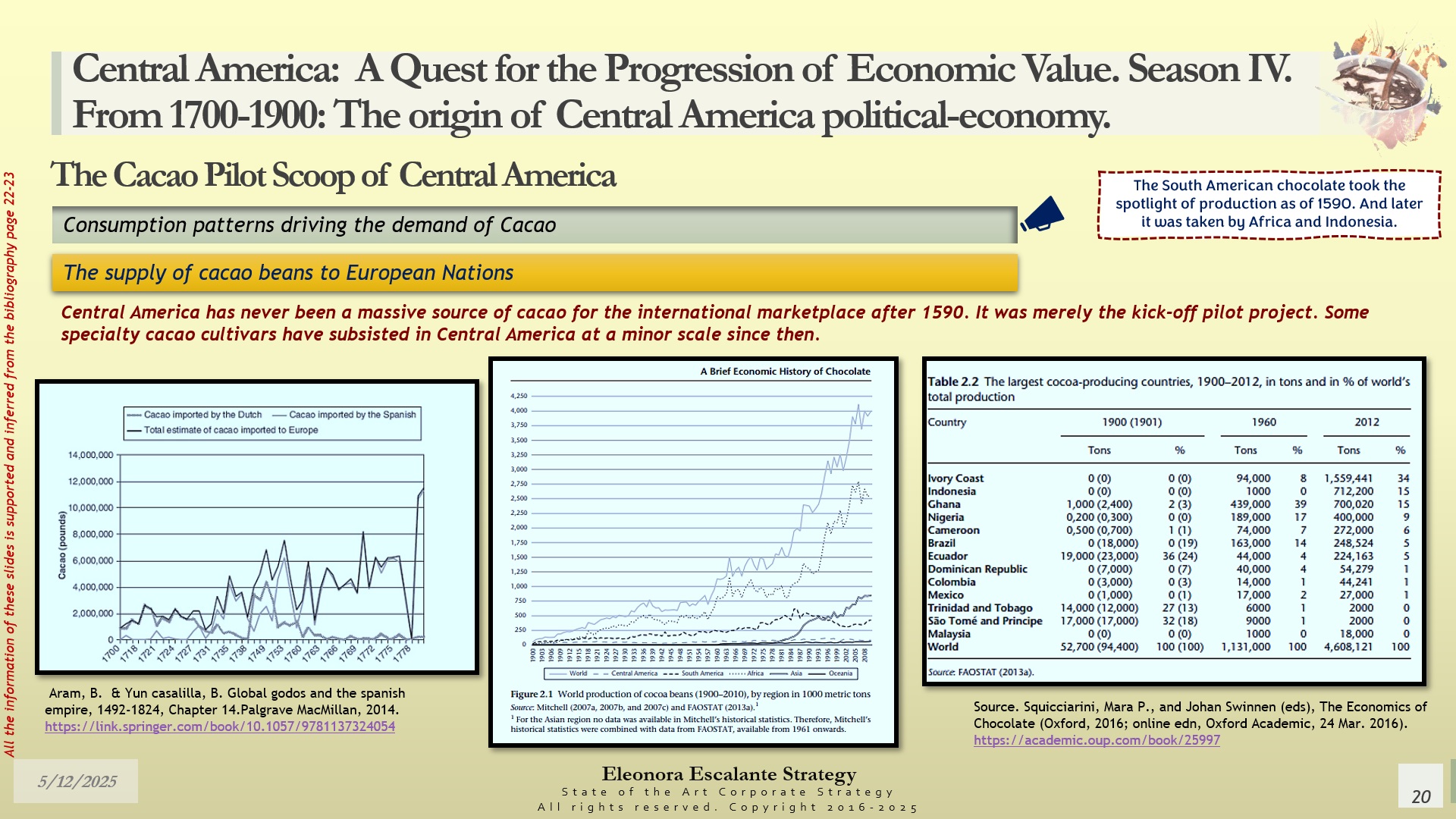

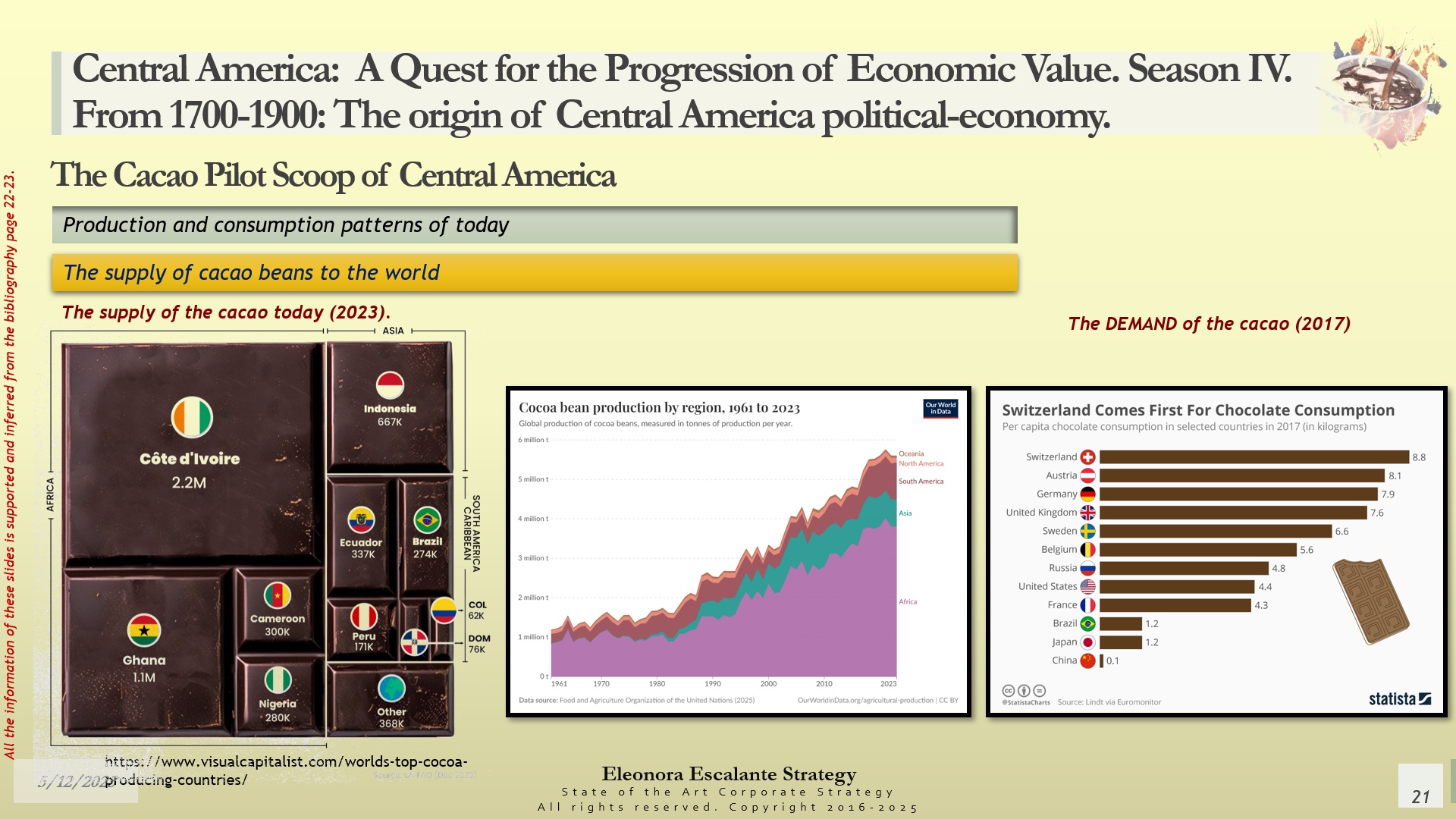

The scoop on the move: Cacao Horizontal Growth Trajectory 18th-19th centuries. Slide 17. We have compared two academic papers about how the cacao production moved from America to the Old World. The first paper from Cilas-Bastide (2020) helps us to observe the trajectory (by year) of how the cacao plantations moved from Central America, to Ecuador, Guyana, parts of Colombia, and Venezuela during the 17th century; and how Brazil (Amazonian Theobroma) was later exported by Portuguese merchants as of the 18th century. When African slavery was abolished in the New World by law, the cacao plantations were introduced and potted in Africa, parts of India, and Asia. This trajectory confirms that cacao producers were constantly looking for cheap human resources for the exploitation of the cacao farms. When the Indian Central American population was almost reduced to zero by 1590, the cacao plantations moved to South America. When African slavery was abolished, during the 20th century, the supremacy of the cacao plantations was moved to African nations, which are currently producing around 70% of it.

Consumption patterns drive the demand for cacao. Slides 18 to 20.

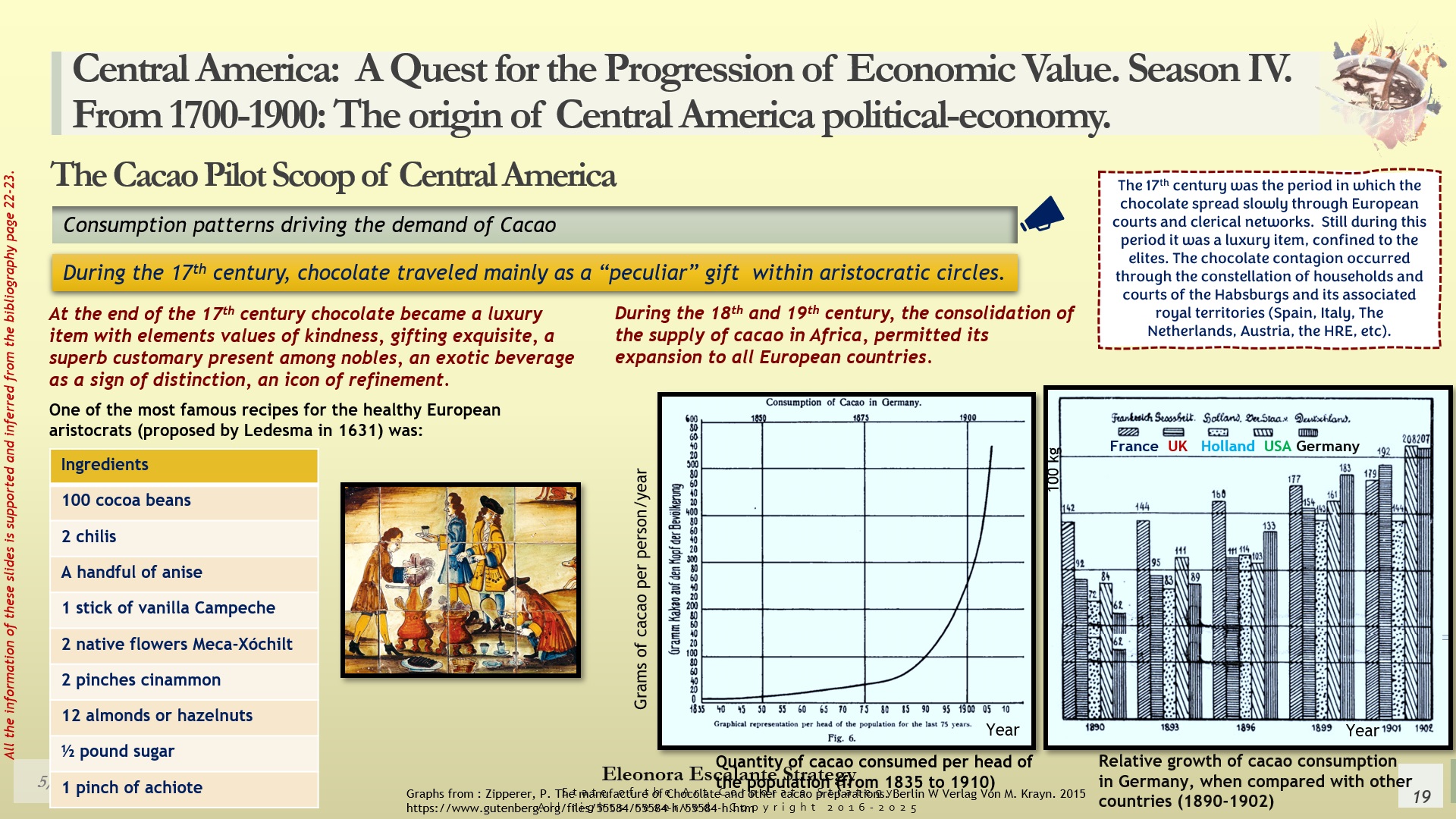

Several authors explain to us how the market demand for cacao occurred. Slide 18 is a shot of that. From the point of view of the pyramid of elements of value (when analyzing value propositions), we conceive that initially, Europeans found chocolate repugnant to their taste. The formation of the chocolate good tasting went through a “sugarization” process in terms of functional values, but the real educational evangelization of the cacao properties started in the New World through the Native Indian females, who transferred the knowledge to the Spaniards, while the Catholic friars and Monastic Orders learned about its benefits. Once the appropriation of the cacao medical knowledge took place, the spreading of the cacao was not immediate. It all began with the upper royal and noble class of Europe, and it later permeated the middle-court class. By the end of the 18th century, chocolate was a game-changer; it stopped being the luxury item of the 17th century, and it was converted into a delicious, energetic beverage that was embraced by the coffee houses and manufacturing workers of England and Germany, while the first Industrial Revolution was taking place.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, cacao was not a priority for Central America. We estimate that the native Indians didn´t want to harvest cacao anymore, after they had almost disappeared from the map. It is probably the indisputable reason why cacao has never recovered in the region anymore. During the 18th century, indigo took some years of relevance, and later it was coffee, as we have studied previously. See slide 19.

Finally, we see a protagonist role of the Dutch in relation to cacao exports during the 18th and 19th centuries. Slide 20 also demonstrates that the production of cocoa beans has never been relevant in Central America as of the year 1590. The production of cacao has moved to Africa and Asia (Côte d’Ivoire, Indonesia, Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon), while the two main centers of production in America are still Brazil and Ecuador.

To be continued…

Closing words. Announcement.

This chapter goes back to the 16th and 17th centuries. The Audiencia de los Confines, known as the Kingdom of Guatemala, was one of the most productive regions for cacao after Pedro de Alvarado’s conquest. This region was one of the most relevant zones for high-quality cacao production. The demand for chocolate has its foundations in history, and Europeans have always been the main clients of it.

Our next chapter is about Sugar-Sugar in Central America. Blessings.

Musical Section.

During season IV of “Central America: A Quest for the Progression of Economic Value,” we will continue displaying prominent virtuosos who play the guitar beautifully. However, we will select younger interpreters who promise to become the new cohort of classical guitarists in the present and future. It is a hard task to include all the guitarists that have reached the top plateau, but trust us, we are trying to embrace them all here.

Today, we have selected Gabriel Bianco, from France, one of the rising stars of the moment. Gabriel won the Guitar Foundation of America International Concert Artist Competition 2008 edition, and from there, he has been unstoppable. His biography is here: https://gabrielbianco-guitar.com/en/biography/. Enjoy!

Thank you for reading http://www.eleonoraescalantestrategy.com. It is a privilege to learn. Blessings.

Sources of reference and Bibliography utilized today. All are listed in the slide document. Additional material will be added when we upload the strategic reflections.

(1) McNeil, Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao (Gainesville, FL, 2006); University Press of Florida, 2006. Chapter 16 by Janine Gasco. https://academic.oup.com/florida-scholarship-online/book/29084

Disclaimer: Eleonora Escalante paints Illustrations in Watercolor. Other types of illustrations or videos (which are not mine) are used for educational purposes ONLY. All are used as Illustrative and non-commercial images. Utilized only informatively for the public good. Nevertheless, most of this blog’s pictures, images, and videos are not mine. Unless otherwise stated, I do not own any lovely photos or images.