Central America: A Quest for the Progression of Economic Value. Bonus-Season V. Episode 1. Sugar Sugar America Part 1.

Happy New Year!. Dear readers, let´s welcome the new year 2026 with the holy spirit of Christ, a renewed vitality that can help us to rekindle our love for God, our loved ones, and our passion to protect the beauty of our planet.

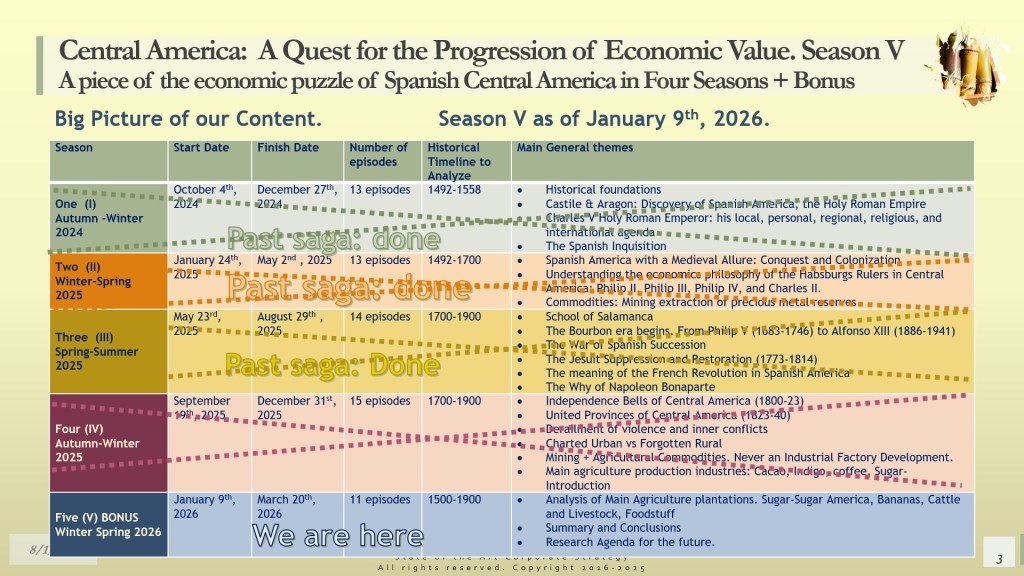

Today is the first master class of 2026. However, it is simply the continuation of what we have been working on since last year. We promise to conclude this mega saga with clear and robust conclusions by March. But we truly needed to extend. If we want to have a good result with all our studies and analysis, we are obliged to grind as much as we can beforehand.

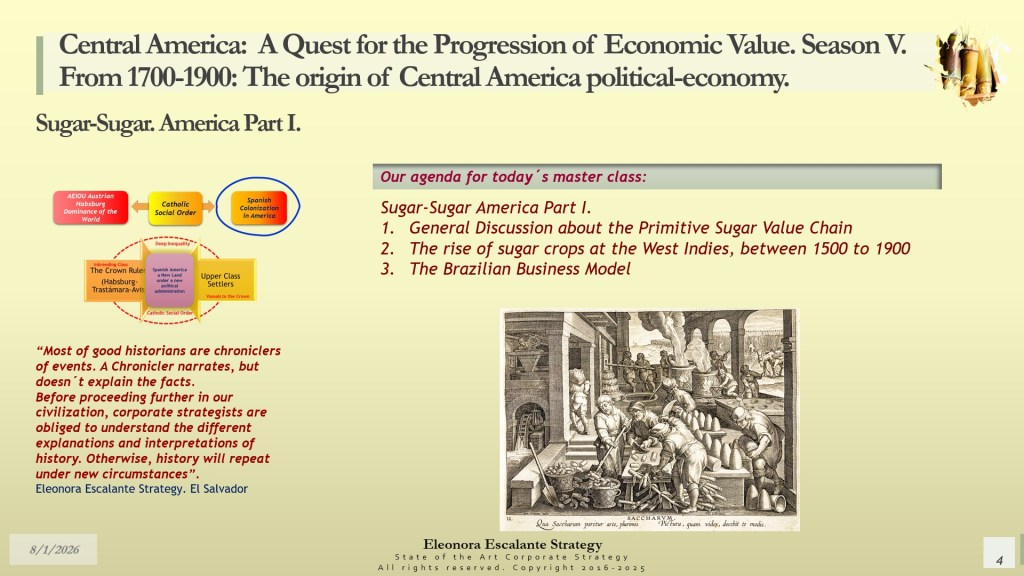

Our document for the strategic reflections of Monday is shown below. The agenda for today is defined in three subjects: (1) General Discussion about the Primitive Sugar Value Chain; (2) The rise of sugar crops in the West Indies, between 1500 and 1900; and (3) The Brazilian Business Model of sugar plantations. As usual, please, we kindly encourage you to read this material and pursue additional research in each of the slides. Feel free to discuss the content with your friends, professors, colleagues, and family. We are arriving at the essential core of all these 4 previous seasons.

We kindly request that you return next Monday, January 12, 2026, to review our additional strategic reflections on this chapter.

We encourage our readers to familiarize themselves with our Friday master class by reviewing the slides over the weekend. We expect you to create ideas that may or may not be strategic reflections. Every Monday, we upload our strategic inferences below. These will appear in the next paragraph. Only then will you be able to compare your own reflections with our introspection.

Additional strategic reflections on this episode. These will appear in the section below on Monday, January 12th, 2026.

Strategic Reflections on “Central America: A quest for the progression of economic value. Bonus Season V. Episode 1. Sugar-Sugar America.”

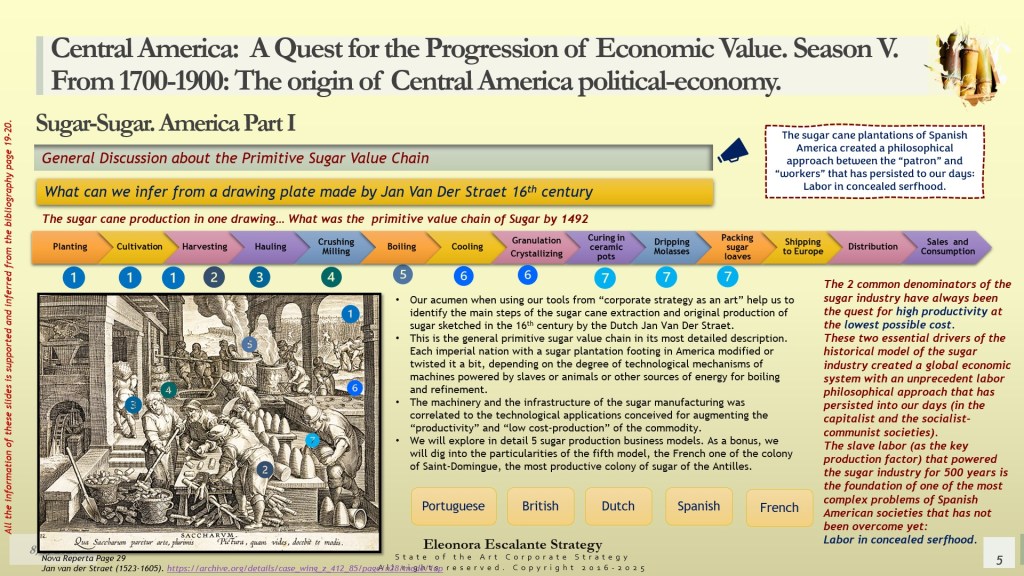

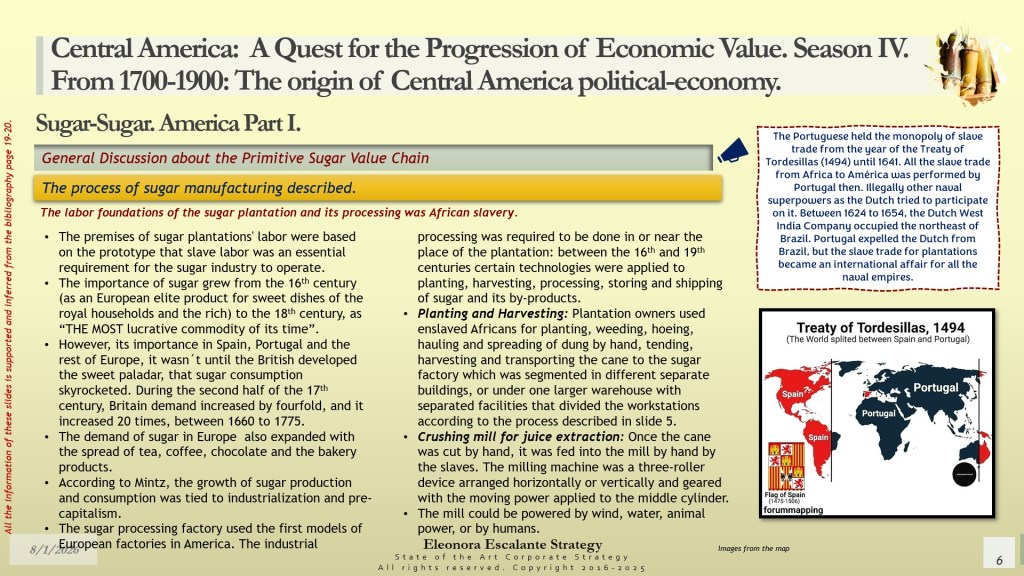

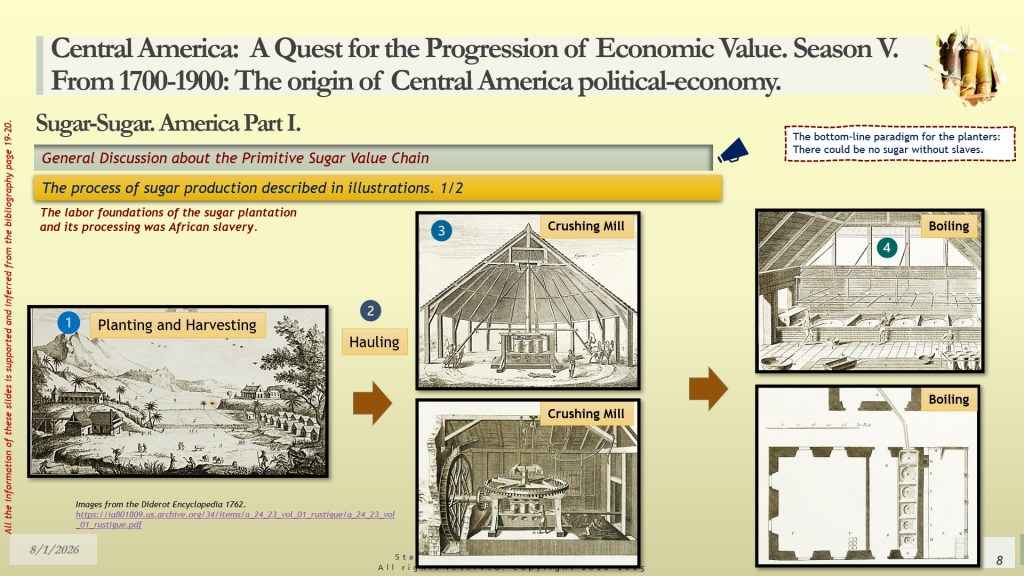

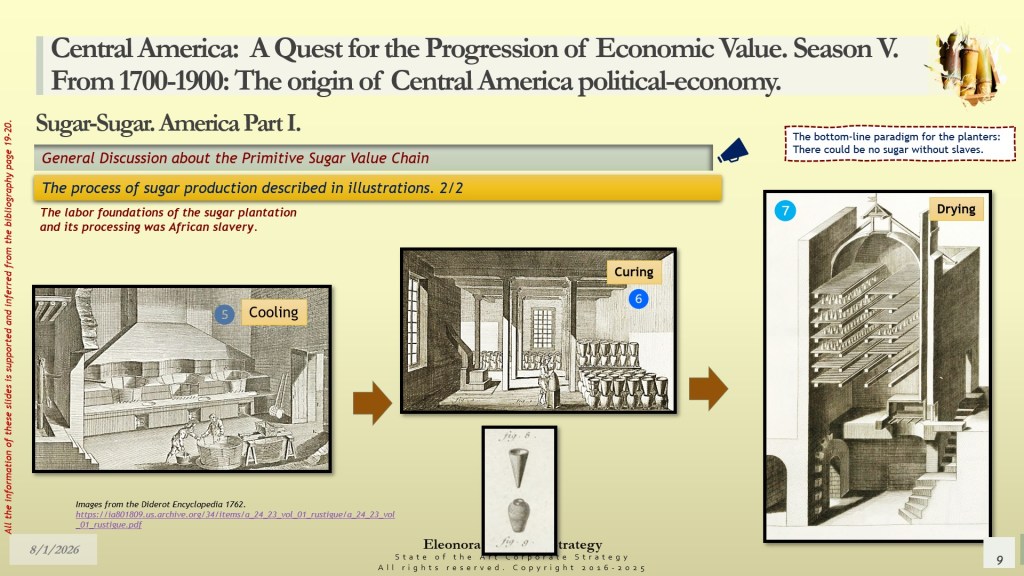

General Discussion about the Primitive Sugar Value Chain. Slides 5 to 9. These slides are self-explanatory.

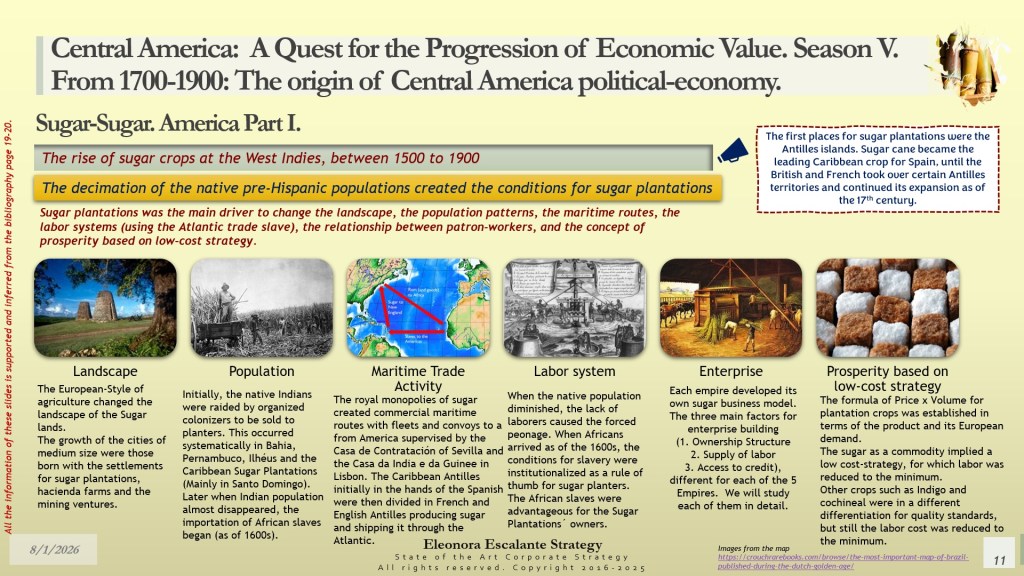

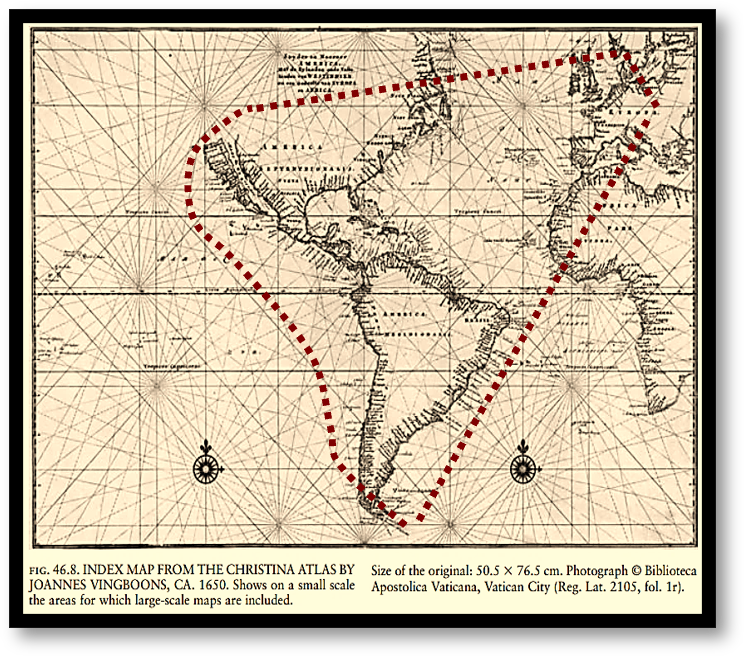

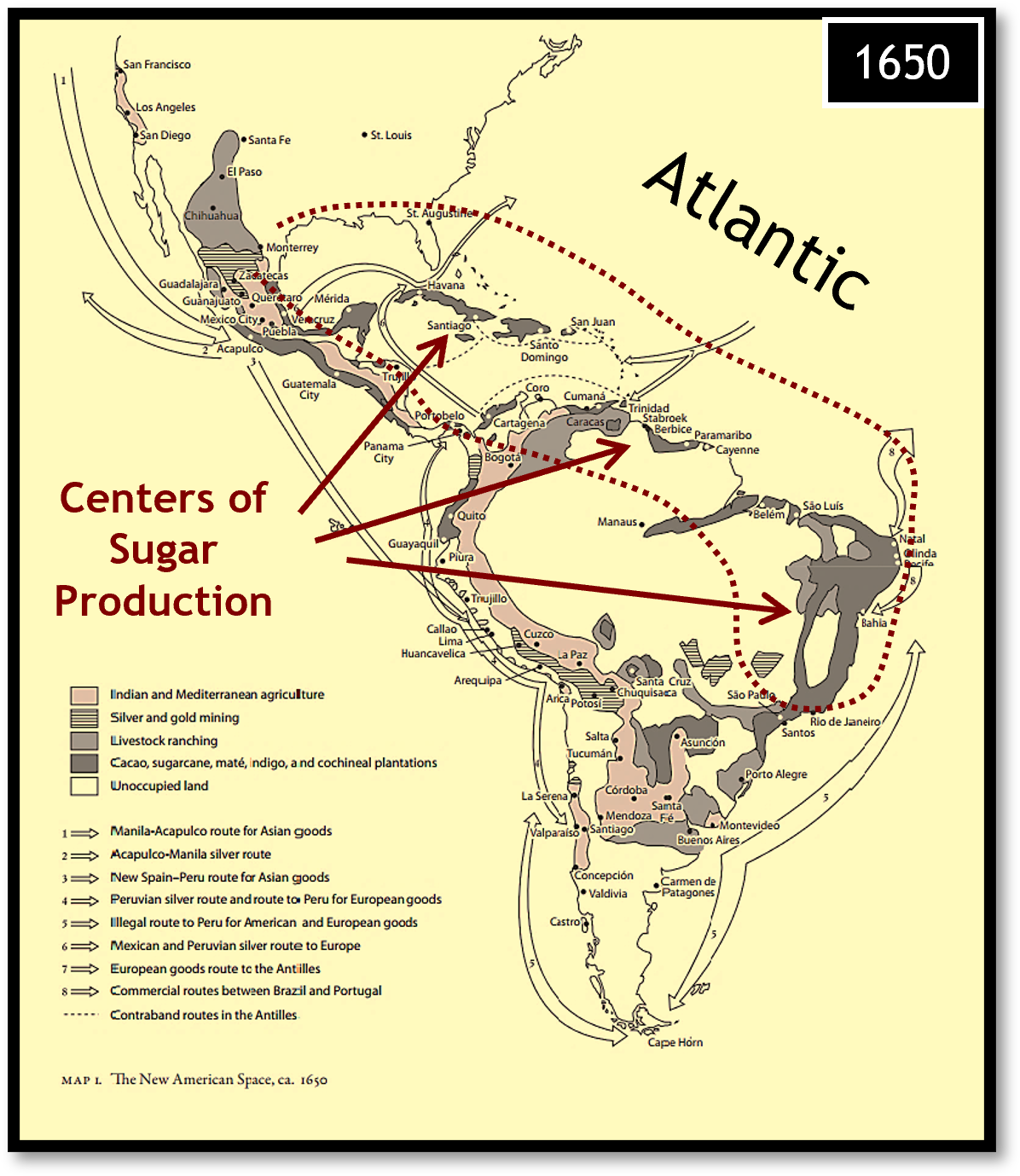

The Rise of Sugar crops at the West Indies 1500-1750. Slides 10 to 11. Our reflection on slide 10 is straightforward. How can we observe the Atlantic from the point of view of the royals of the 16th century, and not with our view of today? Can you analyze the geography of the West Indies, setting yourself in the main ports of Europe (Lisbon, Cadiz, London, Amsterdam, and Seville)? Are you keen enough to see where sugar production was situated? It was all along the Atlantic coast, from São Vicente to most of the parts of the Gulf of México (Louisiana was made a sugar plantation after the 1770s). The Sugar Islands of the Caribbean were at the epicenter of the arrivals coming from Europe. It was like a maritime boarding gate. It was not a free Atlantic Ocean as we see it nowadays, because we have been born on a planet that is divided by nations, separated by the free trade oceans, and that mentality was not in place yet during the period of this analysis. Spanish America was a whole region measured from the European Spanish Habsburg territories, with a huge Atlantic body of water in the middle, and embracing all the American territories. It was the same figure while trading in the Mediterranean, but expanded at least 100 times more. The sugar territories in the Big Atlantic Lake of the Spanish American dynasties were the lands of the islands of the Caribbean, Brazil, and Venezuela. This whole part of the globe was initially called the West Indies.

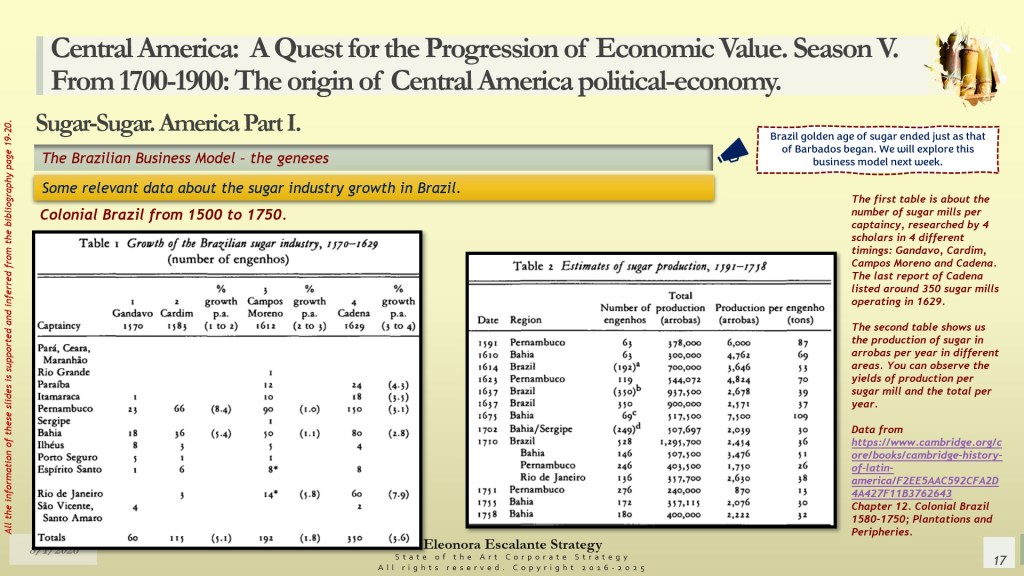

The Brazilian Sugar Business Model: Slides 12-17.

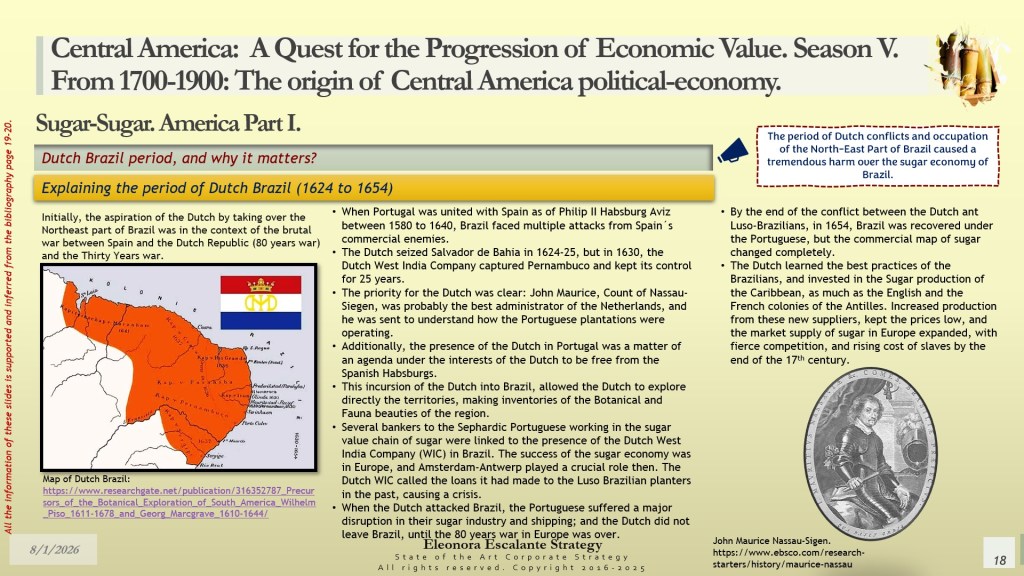

There is no better example than Colonial Brazil to demonstrate how location mattered in the cradle of globalization. The art of choosing the geographic zone where entrepreneurs initiated their most productive crop plantation projects was not fortuitous. Be conscious that these projects were financially backed by kings and emperors, and were implemented operationally by the vassals who owed total obedience to the king. The territorial organization of the New World was in the hands of the 5 main kingdoms (and their respective family dynasties) that discovered America. Sugar plantations held the 5 empires competing with each other, or at least each of them fighting for a portion of the profit pie: France, Spain, Britain, Portugal, and the Netherlands. These 5 dynasties were represented in the following families: Valois-Bourbon, Habsburg-Castile/Aragón, Tudor-Stewart Oldenburg, Aviz-Braganza, and the Nassau, linked to the Protestant German rulers of their time. Each dynasty was organically responsible for populating and creating the conditions for accumulating fortune and exploiting a plethora of goods for the prosperity of each of their kingdoms. But the objective was not to keep their new lands isolated, but populate them fully with European immigrants.

Our hypothesis that these royal families were a huge clan constellation with particular interests, but they were not leading remotely from Europe, has been established since we began Season I. The royal families directly in charge of Spanish America were pivotal to the Royal House of the Habsburg/Castile-Aragon, called the Kingdom of Guatemala, and they organized the rest of the viceroyalties for their monarchical AEIOU strategy. Our hypothesis about European dynasties not separated from the newly discovered lands is more and more valid. They were an intrinsic and ingrained part of the newly discovered territorires. Philosophically, each family held their own way of warfare and their own pursuit of value creation. But given their breeding procreation troubles for perpetuating their leadership, their heads (decision making) were messed up in their intent to collaborate united to find the most promising engine for generating wealth. That is how we perceive numerous conflicts between these families that arose over time. The solution to these internal conflicts gave birth to the concept of the European balance of power system, an effort to stop unnecessary damage between them as of the Peace of Westphalia (1648), a year which coincides with the end of the Eighty Years’ War, and the end of the Dutch Brazil period. As of 1648, every decision maker of each dynasty who felt too behind the pioneers of the discovery of America was obliged to strategize a different war justification (such as the French Revolution, Enlightenment ideas, Napoleonic conflicts, etc), if they wanted to seize or steal the territories of the pioneers. This is why the Spanish/Portuguese concealed kings in America had to maintain a secret profile and build a defensive strategy (such as the Independence movements) through a mosaic of strategic alliances and multiple internal variances in America, in their pursuit to defend their core and beloved “America Latina”.

However, in business, merchants from all these nations were buyers and sellers of stuff. In the entrepreneurial beginning, there is always a pioneer in each industry. In the case of sugar, this frontier-kingdom was Portugal in Brazil, who were the first to try, learn from the mistakes, and rewire their operational formulas for the best mix of Price x Volume. The demand in Europe was established in the Low-Countries.

The Portuguese dynasty is “without any doubt” a unique pioneer sugar case. Beyond historiography, it was through the Portuguese that the horizontal integration of sugar expansion took place in the Caribbean and Brazil. What the Lusitanians learned from the Mediterranean production of sugar in Sicily, they replicated in Madeira and the Canary Islands. The sugar industry on the island of La Española began with the Columbus family, and will be analyzed separately when we explore the Spanish Sugar business model.

From Madeira and Canarias, for the Portuguese, it was natural to replicate the same model in Brazil. The sugar production business model was based on high productivity at low cost (sugar plantations) for the royal earnings. The origins of Brazil were pivotal to sugar. Gold mines came afterward (18th century); consequently, this country was philosophically and socio-economically centered around sugar plantations. Studying the birth of sugar production as an engine for a nation´s development is quite interesting. If you see it with careful attention, Brazil was constituted with its population and territorial organization because of sugar plantations, just as San Luis Potosí (Perú) and Zacatecas (New Spain) developed their populations and territorial organizations because of silver mines. The rationale behind this idea can´t be taken lightly. In America, cities (rural and urban) were formed because of a productive plantation. Not the other way around.

We started with the Brazilian business model of sugar because it was in this region where the highest-yielding industry flourished first, after the discovery and conquest of America. The Aviz royal house was determined to make it profitable as of King Joao III of Portugal (who reigned 1521-57). Afterward, the best practices for soaring productivity tied to a low-cost strategy using African slaves were copied from the Portuguese by the rest of the empires. And from there, the buildup of sugar mills of the Caribbean ocurred later or in parallel to Pernambuco and Bahia.

The Portuguese found not just the accurate marketing “Price x Volume mix” that profited the most, though they implemented a sugar value chain that was established and developed in conjunction with the expelled Portuguese jews residing in the Low Countries. The community of Portuguese Jews residing in the Low Countries was part of this effort. They were inhabitants and merchants of Antwerp and Amsterdam, who dynamically and indirectly helped to use the financial context of the Low Countries for providing loans and conducting the last operational section of the value chain (refining, distribution, and selling).

On the other side of the Atlantic, the Brazilian coast held the most fertile, geographic, and climate-convenient zones. The sugar entrepreneurs of the epoch (loyal vassals to the king), called donatarios, devised a whole value chain using the cheapest resources available (fertile land and African imported slaves), not just to make money and develop the different Brazilian cities under the royal captaincies, but their incremental volumes pushed for the aggregated demand for sugar in Europe using their entrance ports from Lisbon to the Low Countries. Let´s analyze this situation. See slides 12-17.

How did the sugar crops and their factories (engenhos) become one of the most powerful industries of Portugal-Brazil from 1532 to 1750?

Leadership and accompaniment: This only occurred because there was a direct, explicit royal consent and empowerment with the “donatarios” who led the 15 captaincies as of 1549. The first pilot project with sugar mills was conducted by Martim Afonso de Sousa, the Portuguese admiral who commanded the first colonizing expedition to Brazil (1530–33). Martim established the first sugar mill in São Vicente, with funds provided by the Schetz family of Antwerp. In 1549, Governor Tomé de Sousa, not a third-tier courtier, was sent by the king of Portugal to found the capital. Tomé de Sousa was the expert of the king in these matters (as if he were João III), and he came accompanied by the Jesuits who were sent to escort the Governor, to resolve the issues of the Indigenous natives by using the same method as that of New Spain and the kingdom of Guatemala. The leadership established by King João III in de Sousa was not an ordinary delegation. This implies that De Sousa was not a beginner without experience, and his illegitimate nobility made him a “trusted” councilor of Brazilian affairs to the Royal crown. Wherever the Jesuits were, there was a mission Indian village, in which the Jesuit priest played a significant role in the pacification of the aboriginal populations.

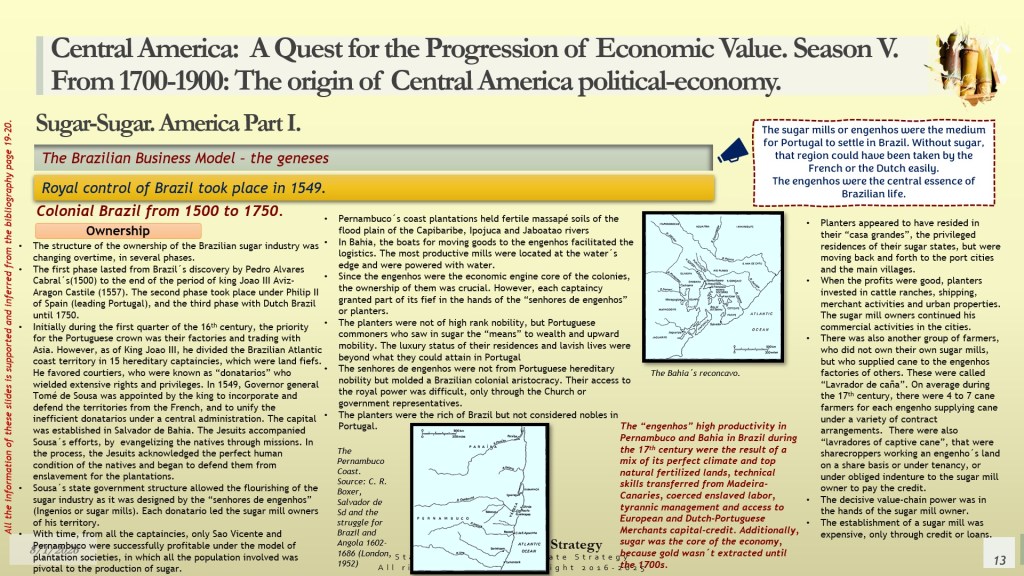

It is important to remember that between 1534 and 1536, fifteen grants, each extending along the coast from ten to a hundred leagues (with three-fifths of them stretching fifty leagues or more), were made to twelve lord-proprietors or captains. Beginning with the Amazon River and extending southward to the present-day state of Santa Catarina, these captaincies and their donatarios were (1):

- Pará (João de Barros and Aires da Cunha);

- Maranhão (Fernão Álvares de Andrade);

- Piaui and Ceará (António Cardoso de Barros);

- Rio Grande (João de Barros and Aires da Cunha);

- Itamaracá (Pero Lopes de Sousa);

- Pernambuco (Duarte Coelho Pereira);

- Bahia (Francisco Pereira Coutinho);

- Ilheus (Jorge Figueiredo Correia);

- Porto Seguro (Pero do Campo Tourinho);

- Espírito Santo (Vasco Fernandes Coutinho);

- São Tomé (Pero de Gois);

- Rio de Janeiro (Martim Afonso de Sousa);

- Santo Amaro (Pero Lopes de Sousa);

- São Vicente (Martim Afonso de Sousa); and

- Santa Ana (Pero Lopes de Sousa)

Ownership structure of the engenhos. Slides 12-13. According to Bethell (2), the ownership structure of the sugar mills was of three types:

- The “senhores of engenhos” received a land grant from the king (as a fief). In this land, they planted sugar cane and built a sugar production, called a sugar mill. During the 16th century, it seems to me that they were not the owners of the land, but the feudal lords of it, which points out that the ultimate owner of Brazil was the Aviz-Habsburg-Braganza family. If the donatarios received a subsidy of land from the king, this donation was in exchange for sugar planting. It is not clear to me if, during the 16th century, the royal crown transferred the land to the descendants of donatarios (it was a hereditary arrangement), who then resold it using the figure of grants “sesmaria”. The sesmarias were the invention of the royal crown who wanted profits from the export of sugar. Anyone in Portugal who had the capital and desire to use the land of Brazil to plant sugar cane was given a royal land called “sesmaria.” The sesmaria was a piece of the king of Portugal’s land, which a person could acquire over time by living and planting, and harvesting sugar cane. Initially, the sesmarias were not homesteads, and each immigrant who lacked the funds to pay for the sesmaria document formalities (300-400 milreis), could squat on unclaimed crown lands. This was illegal, but many first immigrants started to work sugar cane on squatter’s land and then acquired the sesmaria. Irregularities of corruption to obtain sesmarias were common, with numerous animosities, litigation, violence, and political favors from the crown.

- The “lavrador de caña” property:” These were Portuguese farmers who did not own a sugar mill but sold the cane to the “senhores of engenhos.” Usually, there were 4 to 7 cane farmers who supplied cane to the “engenhos” under different contract arrangements. These lavradores de caña held a title to their own land and had possibilities to bargain with the engenhos.

- The “captive lavrador de caña” property: These growers were obligated to serve cane to a particular mill. They were not owners of the land, but paid a rent to the sugar mill owner, a percentage of their half of the sugar produced. These sharecroppers were working an engenho´s lands on a share basis, or as tenants, or under conditions of previous credit for working capital or other debt payments. It is a widespread practice that a senhor de engenho leased their best lands to growers of considerable resources, who could accept 1/3 obligation of sugar. Contracts were common for 9 to 18 years. Each possible product exploitation was operationally designed to satisfy the demands of Europe or intermediate markets on its way to Europe, and to pay debts to the Portuguese merchants who got the credits from the Low Countries.

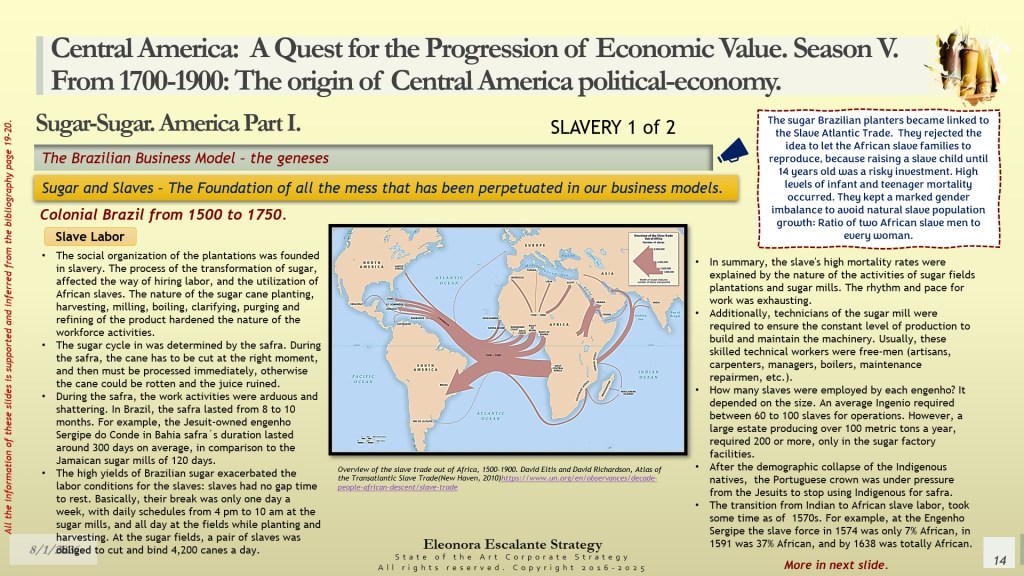

Slave Labor. Slides 14-15.

Land grants from the crown and other illegal arrangements in Brazil were not the key factor of production. Initially, there was so much land that the frontiers between land plots were not relevant in terms of extension or value. However, the most expensive factor of production was the labor force. In terms of value, by 1751, the slaves constituted around 46% of the plantation´s value, while land represented 19%, buildings 18%, and machinery & equipment 23%. The rest 4% was the livestock. In terms of operational costs, the labor-related costs were almost 60%. Slide 14 explains why the Portuguese crown stimulated the use of its direct access from the Brazilian coast to its territories in Africa to access the slaves. African slaves’ initial investment was almost repaid after one year of safra. The analysis of slide 14 is straight to the point to explain why it was profitable to use slaves, and why the Portuguese planters replaced them so easily. Brazil received its slaves mainly from Guinée, the major supplier from Africa during the 16th century, but later shifted to Guinée Bissau during the 18th century. Since the Portuguese were allowed to build the first European fortress in sub-Saharan Africa, for the next 150 years, until the conquest by the Dutch in 1637, Elmina (Mina) was the capital of the Portuguese bases on the Gold Coast of Africa, and it was its main source of slaves. Bahia sugar mills favored the slaves from Elmina because they were considered more capable of withstanding hard labor. After 1770, most of the slaves were seized from Angola. Please re-read slide 15.

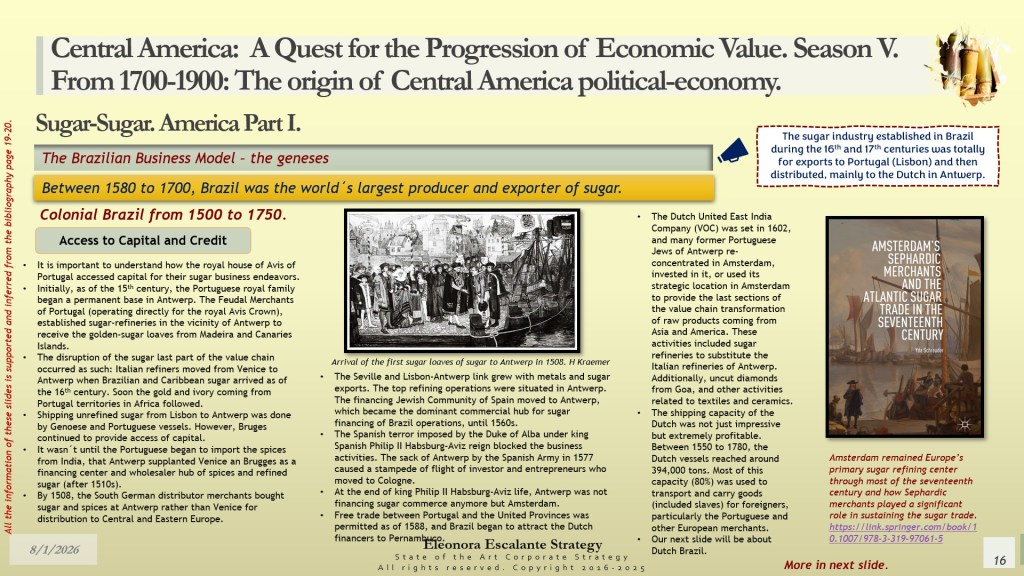

Access to capital and credit. Slide 16.

Slide 16 explains the context of the Dutch Portuguese residing in Antwerp and Amsterdam. After the Antwerp crisis of 1577, the hub for sugar refining moved to Amsterdam throughout most of the 17th century. According to Bethell (2), credit and capital for the capital expenditures (CAPEX) and operational expenses (OPEX) of the sugar mills (engenhos) came from a large variety of sources. During the 16th century, European direct investments from Holland were injected into the Brazilian sugar industry. However, as of the 17th century, loans came from religious orders such as the Charitable Brotherhood of the Misericordia, the Third Orders of Saint Francis and Saint Anthony. By law, these royal monastic orders, approved by the king of Portugal, charged a 6.25% fixed rate. For example, in 1694, the Misericordia brotherhood of Salvador provided 90 loans, with collateral secured by mortgages on agricultural properties, including 24 lands with engenhos (sugar mills) and 47 on cane farms. These loans were used for CAPEX.

For the operational expenses (OPEX), for those senhores de engenhos who couldn´t access European capital, the next alternative was to search for it with private local lenders, principally the merchants, or the traders of slaves. The lending rate was higher, and the repayment promise was against a future crop at a predetermined price. The relationship between debtors and creditors was the real cause of conflicts and internal tension between the players of the Brazilian sugar industry.

In summary, the profit or loss of an engenho was linked to its direct king´s leadership, the ownership structure, its operational efficiency in terms of high-yields of production, the best access to credit, the costs of the slave imported labor, and ultimately, the price of sugar that was affected by international political events.

What does it mean to study the slave labor of the sugar plantations in Brazil (from the 16th to the 19th centuries) and acknowledge the key production factor as slavery?

This is the essence of today´s masterclass.

When an industry is based on low-cost, that immediately triggers a special mix value formula “Price x Volume of Sales.” The objective of a low-cost strategy is to augment the volume as much as it could be possible to reach. It is in the massive amount of sales where the success of profit occurs. The superior rate of profit in terms of a low-cost strategy, for sugar, only occurred because of cheap labor, the location (to reduce the transportation costs to a minimum during the operation and distribution), and the economies of scale. Achieving a competitive advantage over other international rivals relies on higher levels of productivity to fulfill the needs of demand. The European demand was growing exponentially, and sugar shifted from a luxury item to a commodity, mainly because of the reduction of labor costs to a minimum. If the labor was 60% of operational costs, decreasing this factor with slaves (who did not receive a salary and worked under horrendous conditions) meant a low-cost strategy recipe for good profits. If our first global product (sugar) was based on slavery, all our theoretical frameworks for doing business with a low-cost strategy will always privilege the reduction of costs anywhere in the value chain. This is why Artificial Intelligence tools and applications are pursuing and privileging the low-cost strategy, while jeopardizing the human capital that deserves to be pampered, maintained, and paid as middle-class.

Historically, and theoretically, every time that humans choose a low-cost strategy, the factors of cost reduction are always learning (education), economies of scale, product design, and production techniques. And every time these 4 factors become a source of cost advantage, then humans are lowered or downgraded, or expelled from the value chain. There are three additional factors influencing the cost reduction of a product: the cost of raw materials (inputs), the capacity utilization, and the residual differences in operating efficiency. All these 7 factors together determine the company´s unit costs (cost per unit of output) and are called cost drivers (4).

In the case of sugar plantations, the slaves were an inherent crucial part of the manufacturing process, playing a crucial cost driver role in the identification of the 7 factors named above.

In the contemporary case of generative AI, the risk is exponentially greater because it is reducing each of the cost drivers of any product in any corporation, replacing the jobs of humans, while humans have no other place to go or be hired. Unfortunately, the whole value chain of every single industry is being affected by AI without mercy.

To be continued…

Announcement. This is our first publication of 2026. We are blessed with your attention and presence.

We expect this season to be one of the most thoughtful of all. We will close more than a year of analysis and study, and we can´t take it lightly. Our next publication will focus on the Dutch and British sugar plantation business models.

Closing words.

This chapter marks the beginning of our attention to the production of Sugar in Spanish America. As we stated last year, the production of sugar in the Kingdom of Guatemala was not as relevant as that of Brazil and the Caribbean Islands. For this reason, we have refocused all our attention on comprehending the original 5 sugar business models of the 5 main empires: British, French, Spanish, Dutch, and Portuguese. Today, we started with Brazil. All of them produced the same commodity, but differently.

Musical Section.

During our closing bonus season V, we will return to the symphonic philarmonic or camera orchestra compositions.

We have chosen the Neojiba Orquestra Juvenil da Bahia, interpreting the piece Aquarela do Brasil from Ary Barroso. Enjoy!

Thank you for reading http://www.eleonoraescalantestrategy.com. It is a privilege to learn. Blessings.

Sources of reference and Bibliography utilized today. All are listed in the slide document. Additional material will be added when we upload the strategic reflections.

(1) https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/captaincy-system

(2) Bethell, Leslie, ed. The Cambridge History of Latin America. of The Cambridge History of Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-history-of-latin-america/F2EE5AAC592CFA2D4A427F11B3762643

(3) Werren Dean; Latifundia and Land Policy in Nineteenth Century Brazil. Hispanic American Historical Review 1 November 1971; 51 (4): 606–625. https://read.dukeupress.edu/hahr/article/51/4/606/145165/Latifundia-and-Land-Policy-in-Nineteenth-Century

(4) Grant, R. Contemporary Strategy Analysis. Wiley. 2021. Chapters 5 and 7. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Contemporary+Strategy+Analysis%2C+11th+Edition-p-9781119815211

Disclaimer: Eleonora Escalante paints Illustrations in Watercolor. Other types of illustrations or videos (which are not mine) are used for educational purposes ONLY. All are used as Illustrative and non-commercial images. Utilized only informatively for the public good. Nevertheless, most of this blog’s pictures, images, and videos are not mine. Unless otherwise stated, I do not own any lovely photos or images.