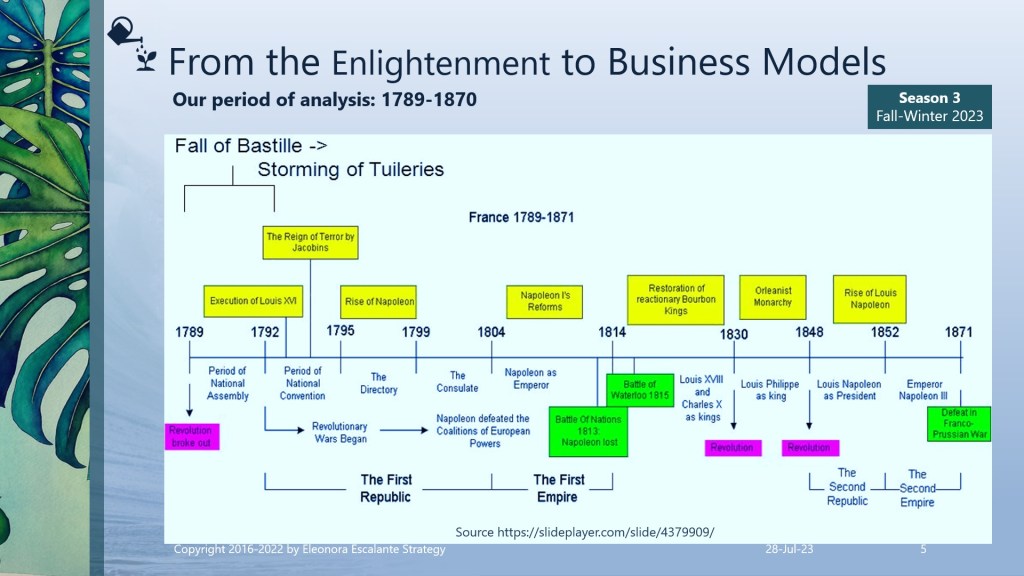

From the Enlightenment to Business Models. Season III. Episode 2. The French Revolution and its Connection to Strategic Management.

Let´s begin.

Our aim with today´s work is to connect the dots between the vital relevant factors of the economic system that arose in the aftermath of the French Revolution (from 1789 to 1870) & how this historical event with further government periods shaped the cradle of strategic management as I studied it. Probably you have never thought of this before, but in terms of the history of business, the French Revolution marked a before and after of the purpose and objectives of business as we know it.

The connection between the political-economic system that was instituted after the French Revolution and its impact on business history (particularly strategic management) was not coming from France but from England. France simply adopted or imported the incipient first theories of capitalism and started to implement them around 50 years after the French Revolution. What surprises me is that several authors and professors identify France as the test of implementing capitalism from scratch? Why does this happen? Why do you think that I included the topic of The French Revolution and its connection to Business/Strategic Management?

Two major reasons explain this. Firstly, it is impossible to be an educated human being (in whatever your discipline or work domain) without understanding the origins and the consequences of the French Revolution. Particularly if we are consultants, strategic management specialists, or professors of business (whatever the area: operations, marketing, human resources, industrial organizations, administration, accounting, and management). I truly recommend including at least a core course on the French Revolution from the perspective of business history in any master’s degree in Business Administration. In the case of an undergraduate degree in business and/or economics, this core course must also be included on a general basis.

Second, I won´t get into the political or economic or social, or cultural details of the French Revolution today. If I do it, and with my expansive brain, I would need at least 3 months to write a saga about this topic next year, and I will consider doing it. Again, my aim is not to shake the political interpretation of the occasion, which has been studied for at least 150 years. My purpose is to link it to business history, and ground in the field of my domain: Strategic management.

When preparing this composition, in my quest to understand the light about it, I had to review again the French Revolution from the perspective of business history. Previously I had read the common general overview. Now, it was my turn to re-read it but from the point of view of business history, which is different than economics. And in the process, I found myself with almost nothing. I searched and searched, for different papers and books, and all that I got was historiography or social-economic-political studies or books of the period. But nothing about business. In addition, not all researchers conceive business history in an integral manner focusing on the value chain as a whole description of the business organization, administration, ethics, strategy, marketing, and logistics. Each of the authors that I read has shared their own views and interpretations, which are partially true, but not the whole truth. So I had to rely again upon historiographers, historians, and historians of economics, from the past and the present.

The task of understanding the repercussions of the French Revolution is not effortless. To digest the aftermath of the French Revolution from the point of view of business history is not irrelevant. It takes several months or years, and whatever I am writing today is a minimum discovery, or the tip of the iceberg. Regardless of the odyssey, we did our search accordingly. On one side I found the strong influence on scholars who favored Karl Marx’s Interpretation in the first half of the 20th century. Bailey Stone (1) in his book “Reinterpreting the French Revolution”, states that the majority of the historians kept Marx’s assumptions to explain the nature of the French Revolution. Here we are stranded with the books and academic reviews of the literature of Jean Jaurès (1914), Albert Mathiez (1922), and Georges Lefebvre (1739). Other authors continued writing with that influence such as Denis Richet (1970), Guy Chaussinand-Nogaret (1976), Adolphe Thiers (1823-1827), Francois Guizot (1829-1832), Albert Soboul (1962), Eric Hobsbawm (1990), Miriam Rosenthal (1988) and Daron Acemoglu (2011). The hypothesis of the French Revolution incidence for these Marxist historians was: “The collapse of the Bourbons´ rule in the late 18th century loomed a struggle between an economically retrograde, feudal aristocracy and the progressive “capitalist bourgeoisie” (1). On the other opposite side of interpretations of the French Revolution, there have been those with a different view who tried to distance themselves from the Marxist conflictive jargon. That is how I explored the material produced by Hyppolite Taine (1878), Edward McChesney Sait (1910), Lilian Knowles (1919), Henri See (1931), Kenji Kawano (1960), Peter MacPhee (1989), Henri Bourne (1928), Thomas Kaiser (1979), Roland Stromberg (1986), Theda Skocpol (1989), Jack Censer (1987), Gail Bossenga (1988), Sheilagh Ogilvie (2014), Patrice Higonnet (1989), Alfred Cobban (1950-1968), John Shovlin (2006), Florin Aftalion (1987), Simon Schama (1989), Francois Furet (1996), Theresa Finley – Raphael Franck – Noel Johnson (2017), Thomas Sargent and Francois Velde (1995), Jeremy Whiteman (2001), Francois Crouzet (1974), Suzanne Desan – Lynn Hunt – William Max Nelson (2013) and other contributors to the motivation of explaining the French Revolution from other different perspectives. For Peter MacPhee (1989), the main argument in relation to the consequences of the French Revolution and Capitalism offers us an idea of the relevance of the settlement of individual property rights. But for MacPhee, between the eve of the French Revolution and 1870, in France was impossible to even consider launching any type of capitalist endeavor. Why? Because the process from fief to private property was starting to take place. In 1960, Kenji Kawano wrote his view about the French Revolution and the progress of capitalism, and he again refused the idea of finding a direct cause and consequences between the French Revolution and the economic structure that could be the foundation of Capitalism. He also rejects that the French Revolution was a result of the conflict between rich farmers and industrial capitalists. In the aftermath of the FR, the roots of capitalism weren´t there yet.

Capitalism was imported from England to France by around the 1860s. The conceptualization of capitalism wasn´t in the minds of the Bourgeoisie immediately after the French Revolution started. After 1789, and during the First French Republic (1792-1804), it was almost impossible to understand what was happening in France in terms of business. All I can grasp from the authors I have cited above is that the process of accommodation or change from feudalism to whatever system was going to rise after, took a slow route in reality, because there was a mess of the further rulers in the aftermath. There was a path of uncertainty and trial/error for those who were leading the changes in the Government. During the First French Empire (1804-1814), the Bourbon Restoration (1814-1830), the July Monarchy, the Second Republic, and the Second French Empire (1830-1870), capitalism as we know it, was not even a word in the horizon by the Third State who represented around 95% of the French population. During the first years after the French Revolution, the priority was to kick out anything and anyone that was linked to the old nobility, the church, and the old-regime court. Reforms and laws were taking place not for capitalism adoption. That was not the goal. The primary concern was to wipe out the old structure of monarchical feudalism in the rural and urban territories. The philosophy to build a new economic system was a trial and error, and somehow a copycat of England reforms that no one really knew how was going to function.

Additionally, Kawano explains that in France, before the French Revolution two parallel systems were running in place: (1) The feudal lord system which was based on privileges of status and social position; and (2) the landownership system, in which private individuals were renting, mortgaging and doing transactions with the productivity results of the peasants. With the abolition of all kinds of feudal systems and the confiscation of the lands from the clergy and nobles in exile, a new form of ownership arose upon the ruins of the feudal system as of 1794: the sharecroppers who bought the land from the former lords, or the plot new owners. Once the land of the Old Lords was passed to the New owners, the French Revolution legitimated a new landowner system for the peasants and the urban Bourgeoisie who wanted to invest their wealth in the land.

From 1789 to 1870 France changing authorities were fighting against the past.

My readings for this post have taught me that during this period, the aggregated causes of the French Revolution were a list of problems that each authority tried to fix. In essence, the causes of the French Revolution were a sum of gradient situations (some endogenous, and some external and/or international), that were added up in an aggregated manner, in a cumulative list of problems that tried to be fixed to erase the past. And the cause of all these cumulative roots was not economic at all. Believe it or not, I have discovered that the foundational origin of the French Revolution as it happened was simply envy and misery. The morals of the French Revolution were not Liberty-Equality-Fraternity. The real principles were envy and suffering (misery). The goal of the French Revolution was to force the downfall of the monarchy and the abolition of feudalism. And every single action that was taken (look at the French Revolution chronology) was aligned for this purpose.

Jeffrey Sachs also refreshed my mind with his brief history of Global Capitalism, and what I will write in the following paragraphs is my own reflection about the connection between the French Revolution and Business/Strategic Management, which is a melting pot work-in-progress consideration that will require some adjustments for sure. Nevertheless, it is our first approximation, so here we go.

Envy and suffering. Two sides of the French Revolution origins.

Mortals weren´t made to see others shine. Most of us can´t handle the emotion and the feeling of looking that others are better off than us. It takes a moral of righteousness, usually assembled through religious values to tame envy. The cousins of envy are greed, jealousy, indifference, and hate. All these anti-values were present in the French Revolution and afterward. This period of time is just an example of envy and the joy of cruelty in the history of humanity that has been repeated over and over and over since pre-historic times. You can find envy in amazing literature oeuvres, in theater plays, in biographies, in wars, and even in political-social-economy upheavals. Let me explain:

- Envy: Enlightened despotism failed in France because the same privileged classes blocked all the reforms during the last years of the Ancient Regime. Turgot, Necker, and Calonne failed. Business in France was mainly agriculture. The industry was occurring at a small-scale level in urban centers, the abundance of numerous small craftsmen or artisan workshops served the different cities and villages. Rural industries that competed with the cultivation of the soil were textiles, spin, and card cotton weaving. And given the high quality of the products in textiles, silk, pottery, and some iron manufacturing, the monarchy administration protected them from the cheap imports of Asia. The textiles workshops were mainly located in the North of France. Apart from that, the luxury of imported goods supplied the wants of those who were positioned in the top 5% of the population, the nobility, and the church. The rest of the inhabitants (95%) were called the Third State. The Bourgeoisie was mainly defined at that time by a new class of shipowners, rich merchants, and those who began to control the rural industries, dominating the previously independent artisans. Additionally, it was confirmed by financiers (bankers), investors in real estate, traders or businessmen (commerce retailers), lawyers, and the rest of the craftsmen-artisans. The legal and studious professionals in medicine coming out of the university were at the high rank of the Bourgeoisie, who lived in urban areas and did no manual labor. The most elevated income layers of the Bourgeoisie (who lived mostly in the cities) were discontented, envious, and jealous of the social, legal, and political privileges of the nobility and the clergy in relation to social claims and land ownership. As historian Henry See explains: “The new class of high-end bourgeoisie was living a sharp sense of discontent and anxiety, among the most enlightened classes who wanted to satisfy the progress they had made and the material prosperity they were enjoying”.

Envy was the cause of the French Revolution at the level of the bourgeoisie, but misery was the cause of the French Revolution at the level of the peasants and the poor citizens of the cities.

2. Misery. The situation of most peasants during the ancient régime was not only miserable but of extreme poverty. Their living conditions are described very well by Henry See (2). In some French regions, peasants lived in the water and in the mud. The food of the peasants was always coarse, and insufficient. Their homes, furniture, and clothing were primitive and precarious. They only had one outfit for winter and another for summer, probably a single pair of shoes. There were notable crises of famine, drought, or riots. The wars were fought beyond the frontiers, but these affected the farmers to sell their products. In one phrase misery was the norm before the French Revolution, and it was observed not only in the rural zones but also in the new city centers of France.

Envy + Misery Together: the basis of the Fury of the French Revolution.

The envy of the bourgeoisie and the misery of the peasants and urban poor created the energy and the fury that moved the French Revolution up to a level of the Reign of Terror. The sum of envy plus misery in 95% of the French population switched slowly into the most solid rage, a vehemence of punishment against the privilege of the nobility and the clergy. When we disembark in uncontrolled feelings or emotions of anger and wrath, humans are capable of horrendous things. In the context of the French Revolution, it is clear to me that capitalism was not even on the table of discussions during the reforms and chaos, and the multiple periods of republics and empires after the French Revolution. There is historical evidence that the industrial revolution didn´t happen but around the 1860s. In consequence, the French Revolution was not driven by business, or by expanding commerce. It was nothing of that in the framework of analysis that I am trying to build now. The only goal in mind after the French Revolution was to abolish the old regime, meanwhile, the nobles left France for the new world. In consequence, the field of the history of business has a duty. To reframe it is our objective for the next generations ahead.

The French Revolution and its connection to business.

People were doing business before, during, and after the French Revolution. What occurred with the installment of property rights over the land, was the shift for people to produce from their own private property, without paying taxes to the monarchy´s wishes. There was also a shift of freedom from the fiefs. With the French Revolution, the framework of business all over Europe was modified. And that changeover resulted in the premise of value creation that is taught in any class of strategic management (as I learned it in 1999) and as it is used in every single company (from microentrepreneurs to multinational corporations). This premise is “maximizing shareholder value”. Sadly, if you observe with careful detail, this premise is tied to envy (and greed) and to avoid the misery of the shareholders at the expense of the environment and the wellbeing of the communities. With this premise installed in all the theories of management, it is obvious that we are not handling well how to make this world a better place. I always ask myself where is Jesuschrist in all this?

Strategic management is the most important segment of business, and we are in debt to understand it in the light of history. In academia, we are in need to create a new field called Business History, or the historical study of business. We are required to go back to the times before Enlightenment influencers and to the 19th century and study business as it was performed by our ancestors. We are required to design one of the most detailed investigation programs in our history. Only by understanding the philosophical roots of the cradle of strategic management, which occurred in the aftermath of the French Revolution, (the century of the first industrial revolution and the capitalism starting point), we will be able to transform our paradigms into better management theories for the future.

Announcement.

Our next publication will be next Friday 4th of August. The theme will be: Different Canons of the Enlightenment Part A. Blessings and thank you for reading our episodes.

Musical Section

We have decided to share classical music from the 19th century today, music from the Halidon Music Youtube channel.

Sources of reference are utilized today.

(2)https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/254010

Disclaimer: Illustrations in Watercolor are painted by Eleonora Escalante. Other types of illustrations or videos (which are not mine) are used for educational purposes ONLY. All are used as Illustrative and non-commercial images. Utilized only informatively for the public good. Nevertheless, most of this blog’s pictures, images, or videos are not mine. I do not own any of the lovely photos or images posted unless otherwise stated.