Central America: A quest for the progression of Economic Value. Season IV. Episode 9. The consolidation of the hacienda model.

Dear readers:

We have updated our material with the most relevant elements for this topic. Our aim for today is to learn the specificities of the “hacienda model” induction approach in Central America. The more I analyze this process, the more surprised I am about how the hand of God was protecting the Native Populations, regardless of the enormous list of iniquities of the Liberals, the eternal landownership conflicts, and the ideological tribulations of the epoch.

To be free from Spain was a huge responsibility. Five nations were trying to find what to do in the middle of new superpowers’ interests (Britain and the USA), in the hub of an uncertain liberal agenda vs a conservative one, in the epicenter of the trade impulse for an Interoceanic channel that was successfully pushed to Panama. How did the concealed Habsburgs of the former Kingdom of Guatemala defend themselves from the Bourbon/liberal radical new ideas? How did they search for the right decision in the midst of so much apprehension, while the international Anglo-Saxon agenda was deciding their future fate? Without the current academic tools to analyze industries, the decision makers of Central America landed on the model of coffee haciendas, but it was a new type of “finca” in comparison to the cacao, cochineal, or indigo past endeavors. In consequence, this episode is a matter of high philosophical corporate strategy core critical activity. This is Eleonora Escalante Strategy essence.

Our agenda for today follows a simple process of opening, development, and closure of the century of independence of Central America. We have gathered philosophical, theoretical, and practical elements that will help us to observe and analyze this century from the point of view of corporate strategists. Not as an economist. Not as historians or anthropologists. We have dedicated several days of the week to understanding a guideline that could truly explain why the Central American leaders decided to bet on the model of finca de café. Here we are, including the wealthy landowners, the Native Mayan elite caciques, and the rest of the new foreigners who helped to shape the model of each nation of the isthmus.

Our content for today:

- The society’s economic structure – opening of the 19th century

- The Consolidation of the Hacienda Model during the 19th century

- The Hacienda Economic Model- end of the 19th century

We request that you return next Monday, November 17th, to read our additional strategic reflections on this chapter.

We encourage our readers to familiarize themselves with our Friday master class by reviewing the slides over the weekend. We expect you to create ideas that may or may not be strategic reflections. Every Monday, we upload our strategic inferences below. These will appear in the next paragraph. Only then will you be able to compare your own reflections with our introspection.

Additional strategic reflections on this episode. These will appear in the section below on Monday, November 17th, 2025.

Strategic Reflections about Episode 9. The Consolidation of the Hacienda Model in Spanish America.

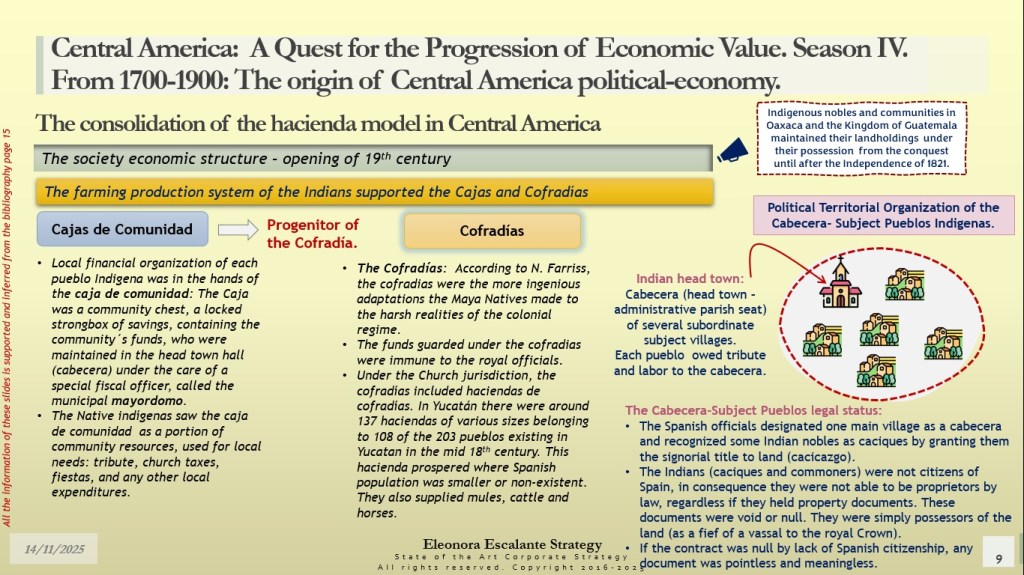

The society’s economic structure – opening of the 19th century. Slides 5 to 9.

It is not easy to provide a regional overview of the hacienda concept of the former kingdom of Guatemala. We have already identified the Central American pattern of Mazinger Z approach: internal united provinces through family colonial ties with a separate external look to the new superpowers of the Americas, Britain, and USA/Germany-Anglo Saxon new lands. In consequence, the Central American Nations, before the Independence movements of 1821, were quite similar but different. Each nation had a specific typology based on at least 5 main key variables:

- The main crop or other product (cattle) that it produced.

- The climate conditions of the land: low-land, high-land, etc.

- Landownership: The type of hacienda and the relation between landowner and workers

- The European cultural origin of the main “hacendados” and their interest groups (with their political caudillos)

- The native indigenous situation and response to the new political-economy policies and their conflicts

Each nation had a different reaction to the new liberalism after Independence. The Morazán UPCA failed. But the second wave of liberalism began in 1870. We have already studied and analyzed it during the last 8 weeks. However, it wasn´t until the second half of the 19th century that the Hacienda Model for a monocultivation of export crops “under free-trade” was ready. It was under this period that the main stakeholders of the nations from the former Habsburg Kingdom of Guatemala began to consider alternatives for their “economic development prosperity.” We are not that sure if these alternatives were forced or influenced to be accepted. We are still in the process of discovering how strong the leverage of the two main superpowers, Britain and the Prussian Kingdoms, was in Central America.

Before 1821, all the plant crop production of this region was sent to Spain. All the Central American nations were setting the pace of their productive endeavors merely to be vacuumed to Cadiz and Sevilla. The King of Spain’s administration did not return any payment. The Criollos and Spanish wealthy producers held the mandate to send all their crops to Spain. It was a servant/slave colonial economy under the “Mother Spain.” The Spanish kings did not have policies for reinvestments in Central America either, besides paying the official posts for the ayuntamientos, judicial councils, governors, archbishops, and some main mayors. Slide 5 shows a comparison of the society’s economic pursuits between 1700 vs 1900. You can immediately observe the core difference that the independence created in the Kingdom of Guatemala. Servant nations to Spain became independent to produce for themselves.

Before proceeding further, we encourage our students to go back in time and click on Episode 4 Independence Bells (1800-23) Part 2. Re-study the slides from 1 to 18 to rebuild your memory about the context of the situation at the beginning of the 19th century. Remember that the hacienda display of Central America was not the same as that of México or Perú. In the kingdom of Guatemala (from Chiapas-Soconusco to Costa Rica), three parallel models were working together, with apparent integrated colonial functioning, but operationally separate: the Indian Native, the Catholic Church system, and the Colonial Spaniard-Criollos urban scheme. Each of the three sub-economic systems was standing and running (with its good and dreadful things). See slide 6. However, the protagonism was in the hands of the Catholic clerics who controlled the Indigenous peoples and kept the regulations of the criollos and Spaniards. The Catholic orders were like the police of the ancient Habsburg kings. When the Bourbon reforms were initiated after the expulsion of the Jesuits in Spanish America, land ownership radically started to change. This situation was under a feudal mentality and a zero industrialization philosophy.

An economic picture of trade at the end of the colonial era (1821) in comparison to trade in 1913 is shown on slide 7. Precious metals were minimal and irrelevant to consider, less than 3% of the GDP of all Central American production (Bethell). The economies of Central America in 1821 had zero income from the exports of indigo, silver, and tobacco; in 1913, the nations of Central America shifted their production matrix to coffee and bananas. With the change of agriculture, land ownership changed. With the change of land ownership, a new socio-political high-end class emerged. And with a new leadership, the political decisions were taken in relation to the interest groups of the “ones” who put up and installed the consecutive liberal regimes of the last quarter of the century. Are you following me?

The haciendas (farming systems) transition is well explained in slide 8. At the beginning of the 19th century, the three farming systems operated under the premises of this slide. However, please remember that the only ones who could access the rural cacicazgos were the Catholic clerics. The Spaniards/Criollos class had limited entry to the “mountains.” Most of the transportation to the city and return to the rural Indian Native communities was done with mules. The cofradías haciendas were an interesting phenomenon (slide 9). In Yucatán (northern part of Petén, next to Belize, area not part of Central America) there were 137 haciendas under the cofradia catholic authority, and these properties were immune to the penetration of the royal Spanish officials. This was the same case of several Mayan communities of the Montaña and the Lacandon Jungle. Just imagine the behemothic difficulty of leading a political territorial organization that was operating with three distinct types of haciendas in Central America. Anyone from outside, particularly the Bourbon reformists and foreigners, would have been surprised and alarmed to observe the lack of uniform basic standards so much required to lead, govern production, and control taxes. Without the Catholic parishes’ supervision, the colonial Central American provinces (rural and urban) would have never been able to endure a two-cohabitation republic’s autonomy (the Native-peoples separated from the Spaniards).

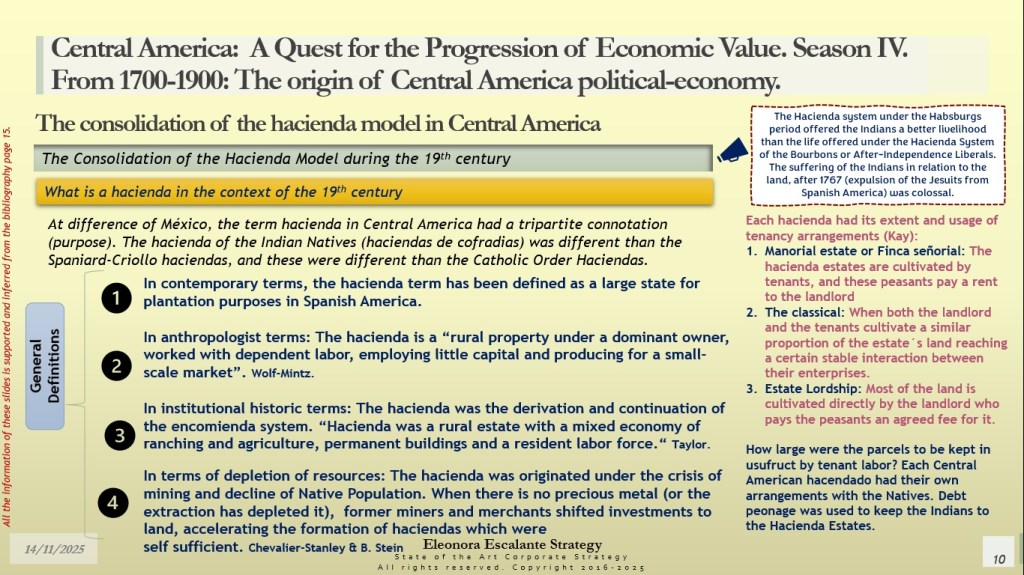

The Consolidation of the Hacienda Model during the 19th Century (slides 10 and 11): Slides 10 and 11.

We attempt to define the term “hacienda” according to several experts in the topic. Slide 10 shows four definitions. However, if we try to define the general label for the Central American haciendas (despite their own particularities), we can introduce the following meaning:

“A Central American hacienda concept that emerged during the 19th century was a rural private property operated with feudal features under an estate landlord who focused on a main agriculture cultivation for international exports or not. The land estate operated with inexpensive permanent tenants and seasonal labor.”

This definition is an effort to consolidate our own regional characterization of the haciendas. It can be applied to the Native Mayan cofradias haciendas, too. It can also be useful to describe the little farms of the Indian peasants who only cultivated native plants, maize, beans, and produced with a large degree of political autonomy. The Indians held a small (tiny) format type of hacienda (in miniature terms), but if you add all the community peasants of a cabecera, you end up with a competitive, enormous-sized conglomeration of haciendas under a “cabecera”; however, the marketable goods were domestic. This was the case of the Mayan highlands under Rafael Carrera. The term “hacienda” can be used to designate the Criollos’ new emerging haciendas expropriated from the church to plant coffee. And it can also be related to the Catholic cleric’s huge farms (with the exception that these haciendas involved different crops and livestock). When the communal lands of the Indian natives and the Catholic Church farms were seized, a unique type of hacienda was being consolidated under private new landownership.

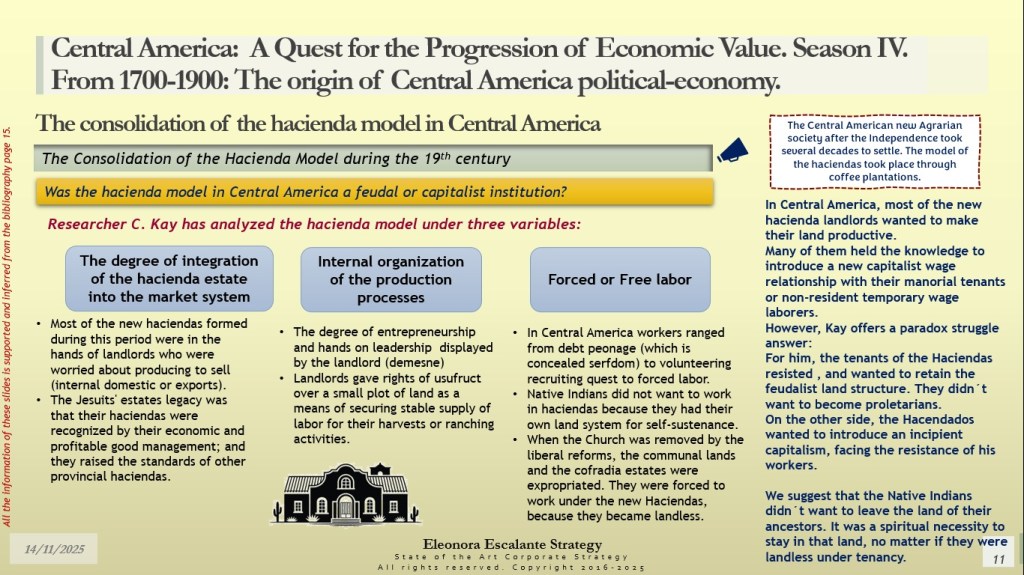

Was the hacienda model in Central America a feudal or a capitalist institution? Slide 11.

Different authors clash about this question. Eleonora Escalante Strategy has a hybrid response for the consolidation of a new type of hacienda under coffee (as of 1870): it was a feudalist business model with capitalist international clients. The Nations of Central America were not structurally developed to become agrarian capitalists until after World War II. The new coffee haciendas of the end of the 19th century were conceived under precapitalist terms, but keeping the mentality of feudalism. Nowadays, this is why we still perceive feudal attitudes in several traditional hegemonic family enterprises, although most of the executive superstructure class has been educated with capitalist premises. The modernization of the Central American corporation began with the baby boomer generation and expanded with the Generation X members of these families. The capitalist business model of the haciendas was developed with people of my generation. Incredible!

During the 19th century, the original roots of the Central American hacienda were additionally attached and sustained in three pillars: (1) The degree of integration of the hacienda into a demand market system (internal domestic, intra-regional, extra-regional, or international exports); (2) Internal organization of the production processes was the core business of the landlord; and (3) the type of labor-forced or voluntary free labor. The “hacendado” was a patriarchal figure who was deeply connected with the liberal government, and he was a firsthand figure in the cultivation and supervision of the quality control of the crops. Even though he could be living in the capital, he was overseeing his business day to day. The delegation to the “sub-jefe de la finca” was impractical, and a few exceptions of entrustment occurred to relatives or illegitimate sons. In the case of hacendado families with “only daughters,” the husband of the offspring became the top “patrón” of the hacienda.

With the new haciendas of the end of the 19th century, the transportation and planning for connectivity infrastructure began. The roads needed to ensure the transportation of the products were financed by national and municipal taxes.

The Hacienda Economic Model-End of the 19th century. Slide 12.

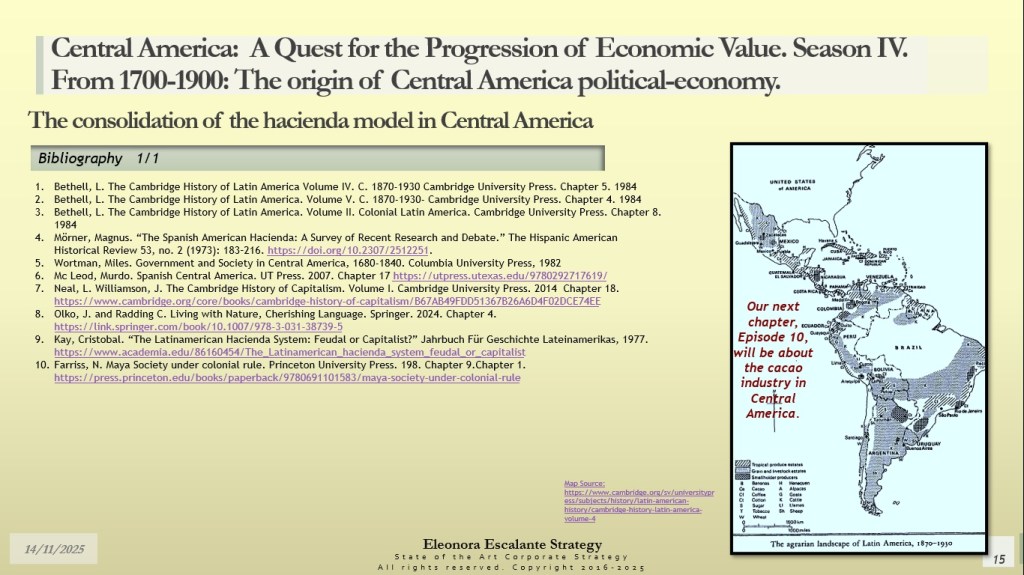

I would like you to observe which nations were the recipients of the exports of Central America. Slide 12 illustrates it. The beneficiaries of our production were associated with Anglo-Saxon recipients, either in Europe (Britain and Germany) or the USA. France was obtaining some from El Salvador and Nicaragua.

Who was paying for the nation-building of Central America: mainly Britain and the Kingdom of Prussia under the royal dynasties of the Hohenzollern, Saxe-Gotha Coburg, and Hannover. Associated with them there were other European royal families, mainly the Wittelsbach and a subtle linkage to the Nassau.

This inference is exceptionally relevant: The 19th century was the world of Queen Victoria, who connected all the royal families of Europe with her descendants.

Central American coffee was being delivered to the citizens of the two main geographic hubs of Queen Victoria and the Hohenzollern kings of Prussia. It was during this century that both superpowers consolidated their hacienda and industrialization models in the USA, and coincidentally, the former kingdom of Guatemala was supplying these two hubs with their main star agricultural production: Coffee!

We wonder how Central America could be an agrarian capitalist cluster of nations if the heads of the world were still dynastic royals? Even though Europe began a transition to an industrialist capitalist model during the 18th-19th centuries, not even the USA held all the characteristics of a pre-capitalist country at that time. Proof of evidence is that the Nicaragua natural interoceanic Vanderbilt channel was used to send mail and gold seekers from San Francisco to/from New York before 1869. This is not an irrelevant piece of information. It is crucial for anyone interested in the economic development of Spanish America. There are certain mindset frameworks and corporate decision-making ways that have not evolved from feudalism.

Take notice please: Currently, a new digital miserable begging economic system is being imposed by “force”, and the result will not be prosperity for the long run, but probably it will be a “new digital slavery” economic model, with the high-risk of no point of return, because the educational competences are being lost in an AI didactic model that eradicates the possibility of deep thinkers, innovative-industrial-operational business modelers and intellectuals, much needed in our societies. The AI era, with its NAIQIs (NAIQI means technologies powered with the combo of Nanotech-Artificial Intelligence-Quantum computing and the Internet) is a negative shortcut for developing countries, which have not developed a critical body of numerous people with the core expertise, skills, and know-how to sustain a national economic model with the middle-class wages of the USA or Switzerland or the Nordic Countries. The commercial monopolies of the NAIQIs’ digital economy do not leave anything to our countries, but these keep the same old feudal structure of the past, now at the technological level.

Central America is not ready for the AI era. Our structural foundations are too fragile, still evolving from feudalism, without capitalist industrialist roots, and this fact (proven by economists and historians) will not be able to overcome the obscure side of the digital economy, which is its digital begging and modern slavery. A good metaphor about jumping into the AI economy is like passing the leadership baton to a teenager, who might be a digital native with tons of ingenious, brilliant ideas, but still has not built his 360-degree vision, nor his emotional maturity to comprehend all the consequences of a mistaken paradigm, and a dangerous, high-risk economic design. It is not his fault. It requires a lot of witlessness to pass the royal wand to a teenager before the time is right. It is part of his lack of brain development. Leaders only reach their peak of good judgement and emotional intelligence between 55 to 60 years old, and there are many who never attain it, given their lack of integral preparation for it.

To be continued…

Closing words. Announcement.

How to perform corporate strategy decision-making for a society in transition? What type of intuition was guiding the Central American caudillos and the rest of the stakeholders of the newly formed nations? It takes more than an orchestrated effort to keep a region that was desperately looking for a monetary recipe for success. The foundations of Central America’s agrarian capitalism were feudal. Building an economic model for an agricultural commodity was so hard because a political and landownership metamorphosis was underway. Additionally, the region was important for the nascent United States of America, and, territorially, certain previous dynastic arrangements kept the former Kingdom of Guatemala affixed to North America´s plenipotentiary mission in the Americas.

Our next chapter is Episode 10, which will be about “The Golden Bean of Coffee in Central America.” We will kick off with this crop, instead of cacao. Why? We have been analyzing all the conditions and contextual factors of the 19th century, and it looks convenient to proceed with it. Cacao will be studied on the 5th of December. Thank you.

Musical Section.

During season IV of “Central America: A Quest for the Progression of Economic Value,” we will continue displaying prominent virtuosos who play the guitar beautifully. However, we will select younger interpreters who promise to become the new cohort of classical guitarists in the present and future. It is a hard task to include all the guitarists that have reached the top plateau, but trust us, we are trying to embrace them all here.

Today, it is the turn of a professor. Her name is Yennee Lee. She grabbed my musical attention with this song, “Autumn Leaves”. I have been listening to it several times during the week. This song reminds me of my student years living in New York City. Yenne is from South Korea and holds a fantastic academic preparation: A doctorate from the Manhattan School of Music, a master’s degree from Mannes College of Music, and a bachelor’s degree from Seoul National University. https://yennelee.com/

Thank you for reading http://www.eleonoraescalantestrategy.com. It is a privilege to learn. Blessings.

Sources of reference and Bibliography utilized today. All are listed in the slide document. Additional material will be added when we upload the strategic reflections.

Disclaimer: Eleonora Escalante paints Illustrations in Watercolor. Other types of illustrations or videos (which are not mine) are used for educational purposes ONLY. All are used as Illustrative and non-commercial images. Utilized only informatively for the public good. Nevertheless, most of this blog’s pictures, images, and videos are not mine. Unless otherwise stated, I do not own any lovely photos or images.