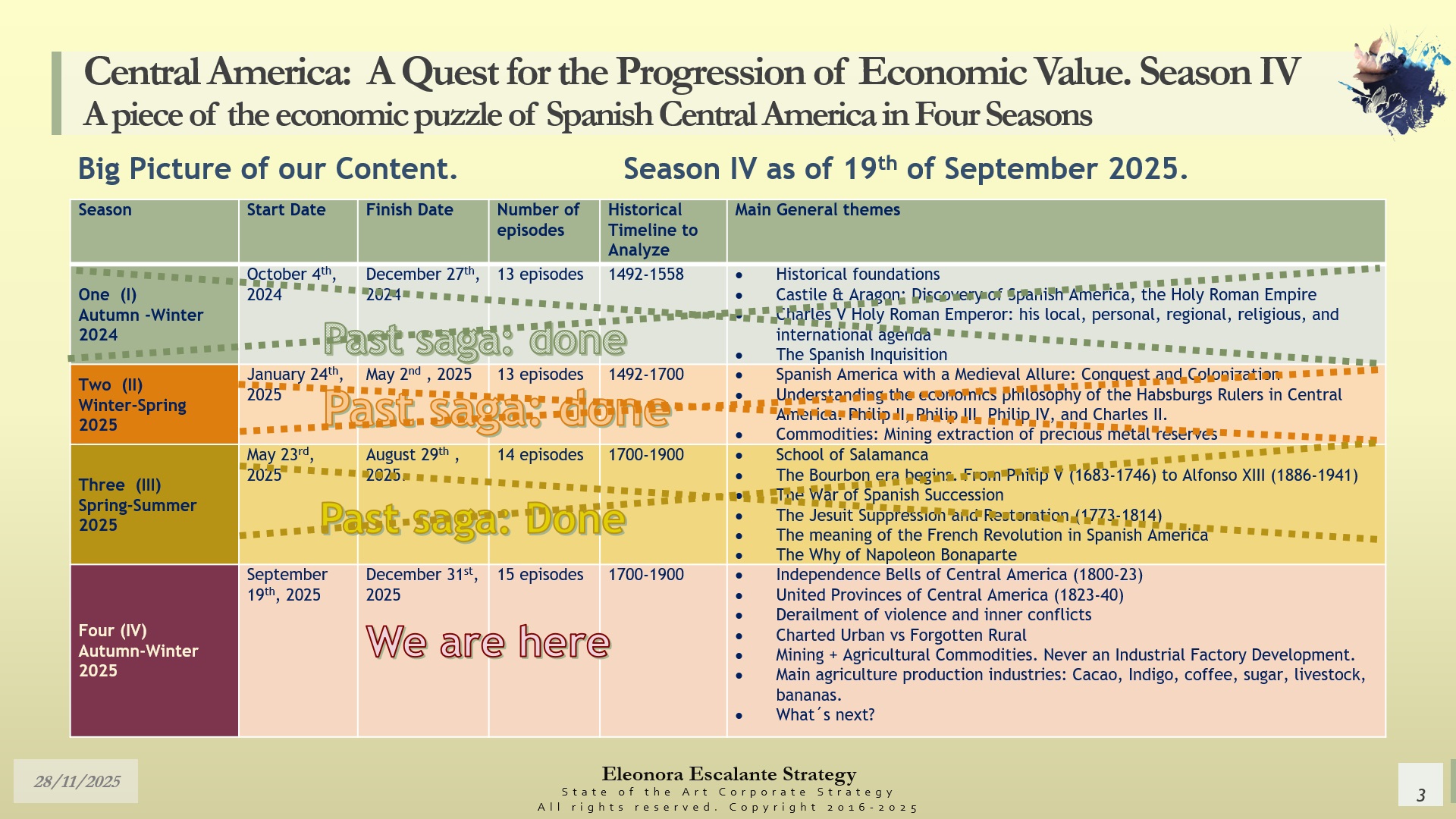

Central America: A Quest for the Progression of Economic Value. Season IV. Episode 11. The Indigo Courage in Central America.

Dear readers:

Wishing you a fantastic last day of November. To readers who celebrate Thanksgiving, my best wishes and hugs are sent from El Salvador to your dwellings. Now, let´s begin. Our objective for our masterclass of today is to dig deeper into the monarchical strategy of the golden blue epoch of Indigo (18th-19th centuries).

Our agenda for today covers 4 themes:

1. From Invasion to Transformation and Formation of the Land for Indigo.

2. How did indigo plantations begin in the kingdom of Guatemala

3. Indigo 101.

4. Indigo production and trade from 1770 to 1830

As usual, we share our master class frame of reference with our readers on Fridays. We expect you to get acquainted with the topic and expand your research over the weekend. The bibliography is always attached at the end of the following presentation slides. Feel free to download this document, print it, and write notes. Do not forget to discuss this subject with your loved ones.

We request that you return next Monday, December 1st, to read our additional strategic reflections on this chapter.

We encourage our readers to familiarize themselves with our Friday master class by reviewing the slides over the weekend. We expect you to create ideas that may or may not be strategic reflections. Every Monday, we upload our strategic inferences below. These will appear in the next paragraph. Only then will you be able to compare your own reflections with our introspection.

Additional strategic reflections on this episode. These will appear in the section below on Monday, December 1st, 2025.

Strategic Reflections Section. Central America: A quest for the progression of economic value. Season VI. Episode 11. The Indigo Courage in Central America.

The essence of today´s analysis. Again, our aim is not to perpetuate or revolve the pain of our history to point fingers at accusing the current digital economic endeavors of the royal empires’ descendants. None of the present heirs of the royal families involved in the discovery and transformation of the Native American landscape of America is guilty of what their ancestors did or allowed others to do. We hope you understand that we don´t shake things up to hurt those who are trying to build their new technological empires. Each generation is responsible for its own decision-making mistakes. Including those occurring now because of historical ignorance. Our strategic guideline with this saga is to open the eyes of the new decision makers who are ruining the well-being of people and devastating the middle-class growth with wrong business models. We are a studious academic corporate strategy research house based in El Salvador. Our goal is to put the trade economic history over a table of multidisciplinary reflection, not only to acknowledge the situation, but to see it with eyes of mercy. The new technological empires are not going to help us overcome the sad past. The AI is too much for our civilization. Only when we recognize and are touched by the factual reasons of our past economic decision-making, only then will we be able to change the essence of those mistakes. For a better future for the new generations. Otherwise, by occulting the real truth of our past, history will repeat, under new circumstances (as is happening now with the digital giga economy). We can´t carry on NAIQI (Nanotech-Artificial Intelligence-Quantum computing and the Internet) business models based on historical ignorance, just to create a new global cohort of digital beggars with excruciating spinal pains and damaged brains because of excessive usage of generative AI applications. We are not writing for any political reason, nor because we have been paid for it. We are producing this content because we hold a deep sense of “milk of human kindness for our next generations”. Can you grasp our point? Good enough. Let´s begin.

The philosophical premises behind indigo globalization. The cultivation of indigo as a commodity for global trade occurred in the context of the philosophical premise that privileged the European long-distance transfer of goods produced at the lowest cost, in the colonial territories of the four main empires operating during the period of our study (the 18th-19th centuries). These empires were (1) the Spanish (under the descendants of the Habsburg-Valois/Castile-Aragon in Spanish America), but underneath the Bourbon-Wittelsbach/Farnese-Wittelsbach leadership in Spain-France; (2) the French (under the Bourbon Wittelsbach/Farnese); (3) the British (under the Hannover Hohenzollern/Saxe-Gotha); and (4) the Portuguese (Braganza Wittelsbach/Habsburg-Bourbon).

Please remember that the British Hannover last name tag means Guelph (or Welf)-Wittelsbach/Welf of Brunswick-Luneburg with a touch of Wettin-Saxony. The monarchical leadership of all these dynastic families controlled the whole picture of global trade. Every single economic decision was their ultimate responsibility, and whatever they permitted or tolerated through their trading enterprises as VOC or EIC, the rest of the intermediary merchants, their value chains of logistics, factories in Asia, or agriculture haciendas in America, was not a fortuity. The system was designed and operated with the expansion of the new territories in which the conquered populations became subjects (vassals, subordinates, or slaves paying tribute). The whole mercantilist system was designed to use the factors of production in the cheapest possible way. Their trade system was designed to generate maximum profits for these royal families, governments (courts), and their interest groups.

Their value proposition was to produce at the lowest possible cost, with the available technologies of the time, searching for efficiency and productivity, transferring the goods at the cheapest rate to their ports of distribution, and then re-exporting them to the cities and villages of their European domains. The industrialization (first industrial revolution) began with that philosophy. And sadly, every wave of post-industrial disruptions has followed the same core frame of reference. Every single economic endeavor of the 18th and 19th centuries has followed 4 simple historical unethical laws that were inherited by these dynastic empires since the Mesopotamian cuneiform records of 3000 BCE. See Niels Steensgaard’s basics with our added analysis (1).

- The law of unpredictability of success: every single product was a bet for success or failure, depending on the demand and the aspirations of the European markets that imported them. However, when the traders (merchants) realized that they could manipulate the conditions of demand and supply, the whole mercantilist system became corrupted at its core.

- The law of cost-reducing innovation: Each European empire was looking for sales growth and expansion of its production to serve the final markets. However, the delivery of those goods involved multiple intermediaries, which drained the profits. In consequence, the low-cost strategy was favored. Competition in commodities was fierce, producers and merchants were conscious of the fluctuations of demand and supply, while surfing the uncertain external factors (as climate events, earthquakes, plagues to the cultivars, etc). They were also aware of how their productive rivals in other parts of the world were driving new initiatives for saving every penny or reducing transaction costs. Labor was the factor of production in which the producers and merchants did not lose any opportunity to skimp. Any new territory that held conquered populations meant human subjects that could be treated as slaves. This is the rationale that they pursued when they took Africans to work in plantations under horrific captivity conditions. For producers and traders, if they wanted to survive in such a competitive market to flourish economically, they justified slavery. Can you see why this law is also morally incorrect?

- The law of saturation: The old story of our ancestors’ economics was to saturate markets to reduce prices. Any luxury item can become a commodity if there is an ubiquitous inundation of its supply. This is the story of indigo. While it was a symbol of lavish and colorful pigment opulence used only by the royals, it did not hurt anyone. Indigo could be produced in small amounts without hurting the producers. When it became massive and expanded all over Europe and America, the inhumane and unhealthy conditions of its production affected all the workers involved, and it represented a massive flow of income for Britain and everyone involved in its value chain. Most of the trade commodities of the 18th and 19th centuries were affected by this law. The same applied to the Asian Spices competitive market: by inundating with its supply, then the spice prices were reduced, the demand was stimulated, and the markets were totally saturated.

- The law of geographical transfer: According to Niels Steensgaard, this is a variant of the law of cost-reducing innovation (law number 2). “When a commodity had become popular, its production was transferred to other areas that were effectively better in terms of abundant factors of production or that were closer to the main markets. Sugar, indigo, and ginger are clear examples of this law, translated later into a competitive strategy. The eastward transfer of tobacco cultivation is interesting because it meant competition between a cheaper, low-quality product produced by European peasants and a more expensive, high-quality product produced by slave labor.” The case of Indigo in Central America is the clearest example of this philosophical mindset. Whenever an empire (in this case Britain) saw a location with the cheapest conditions of production, where they could control the whole value chain, then they reallocated it to other territories. But this law is not also for Britain, but for the Dutch, the Spanish (with silver), and the French empires. Coming back to indigo, this is what happened when the blue-dye production of the kingdom of Guatemala was stopped, and a new, cheaper center of production was moved to Bengal-Bihar in India as of the end of the 18th century.

Now that we have revisited the premises of mercantilism used by the main trading empires of the 18th and 19th centuries, it is our turn to reflect on the material we shared last Friday. Most of the slides are clear and self-explanatory.

- From Invasion to transformation to the formation of the kingdom of Guatemala land for indigo. Slides 5 and 6.

Let´s remember that we are situated in the 18th century, when the kingdom of Guatemala was not yet independent from Spain. After 1821, during the 19th century, only a few significant indigo properties in El Salvador continued, because the liberal transformation of the land as a productive factor was moving to coffee plantations as of 1870. These two slides reminisce about the big picture of the kingdom of Guatemala. The royal household of the kingdom of Guatemala was a composite network of provinces under the supervision and control of the Catholic Church. Europe was not home for the concealed royals living in the region. These families were obliged to assemble their ways of living beyond the self-sustenance of food. The kingdom of the Audiencia de Guatemala required imported products, and its dwellers, naturally, exchanged whatever was available, formerly under the Habsburg royal order of three economic systems (the Native-Indian communal lands, the Catholic Church cofradia financing system, and the hacienda Spanish model). The tripartite economic system remained untouched for almost the whole 18th century, until 1770. According to Elinor Melville (2), a three stage process was occurring since 1523: (1) The invasion and appropriation of the Americas by Spanish American citizens accompanied with their livestock and domestic species; (2) the transformation of the indigenous native environments; (3) the formation of a new economic order, specifically organized around the production for exports at the cheapest cost. We have explained this process in detail on slide 6. From this slide, we can infer that the process of the Guatemalan kingdom for economic wealth exports was not automatic. It has taken more than 500 years, and it continues nowadays. During the first 300 years, European agropastoralism operated in parallel to the Native indigenous economic subsistence system. Meanwhile, the indigenous crops continued in their domain areas with the Catholic friars around. This status quo remained intact for those 3 centuries, as when Charles V HRE encountered it. When the waves of change expelled the Catholic Orders from the region, the transformation of the indigenous landscape began to change. The formation of the indigo export system was proof of evidence that a commodity product was the channel to change the political-economic order of the kingdom, while governments (conservative or political) were usually aligned for this to happen. Those who lead the demand for those products/services (in the case of indigo, it was Britain) could change the destiny of populations, for better or for worse.

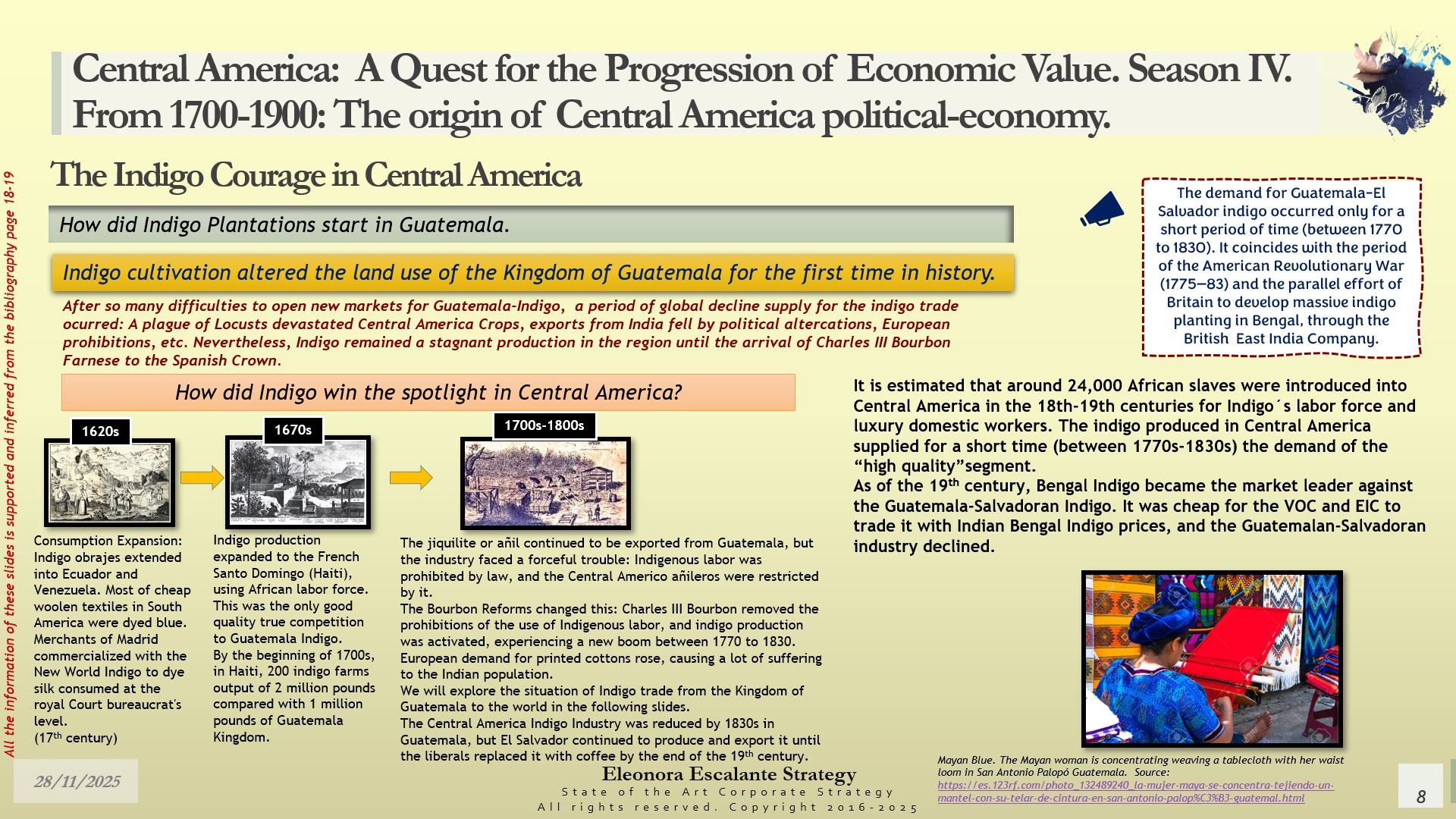

2. How did indigo plantations start in the Kingdom of Guatemala? Slides 7 and 8.

Under the Spanish Habsburg regime, the Guatemalan Indigo never picked up as a relevant crop for exports. Indigora plants thrived in Central America before the arrival of the Spaniards. It was used for domestic healing and painting attributes by the Mayans and Aztecs. Indigo plants were also abundant in China, India (South-Southeast Asia). Indigo manufacturing was an age-old legacy. It was extracted from plants in ancient times (3000-4000 BCE), to the point that indigo got its name because the plant pigment was imported from the Indus Valley to Europe through the Mediterranean-Levant traders. Later, after the age of maritime discovery, the pigments reached Europe through Portuguese and other European traders. Subsequently, it was also subsisting in Britain colonies as South Carolina. Slides 7 and 8 show the main relevant information about the transformation of indigo from 1523 to the late 1800s. We explain the voyage of the Indigofera tinctoria that mingled with the Indigo Suffruticosa and Indigo Guatemalensis, and how it was later adapted, sown, and manufactured to supply the demand for European dyed textiles during the 18th century. It is important to emphasize that the Guatemalan Indigo formula strategy commenced in the 16th century, but it stayed stagnant, because Indian native laborers were getting sick with it, and we are convinced that under the strict supervision of the Catholic Church, the royal edict of restricting the indigenous labor in indigo kept them (somehow) protected for a while. Indigo labor then turned to African slaves and the rest of the castes. When the Bourbon administration arrived in Spanish America, Indigo commenced to ascend during the 18th century with entrepreneurs such as the Marqués de Aycinena and others from El Salvador. It is estimated that around 24,000 African slaves were introduced into the Guatemalan kingdom for the Indigo labor force and for high-end servants of the Spaniard colonies. Sadly, when the Bourbon-Wittelsbach reforms invalidated the royal protection of the Indian labor, that is how we arrive at slide 9.

3. Indigo 101. Slides 9 to 11.

We have produced a simple value chain analysis on slide 9. Our arguments are exhibited to explain the main details of indigo dye production, from planting to operational processing, to how the final product was packaged for its delivery and distribution. We have discovered two waves of indigo production in the Kingdom of Guatemala. The first wave occurred during the 16th century, until King Philip II Habsburg-Aviz prohibited indigenous labor for 150 years. The second wave occurred with the ascension of King Charles III Bourbon Farnese into power. Indigo production restarted after the expulsion of the Catholic orders, the seizure of their properties, and the consolidation of the liberal governments in the region. This came to pass between 1770 to 1830. During this second wave, the Kingdom of Guatemala indigo core business was coming out of El Salvador. Scholar H. Erquicia (3) has made an archaeological detailed inventory of the royal obrajes of indigo in El Salvador, particularly for the departments of La Paz and San Vicente. “At the province of San Salvador, during the second half of the 18th century, there were 267 haciendas with 618 obrajes for indigo manufacturing, and by the start of the 19th century, there were 447 haciendas of cattle and indigo”.

The toxic side of the Indigo operational process is shown in slide 10. It is essential to highlight that the operation process of indigo was fundamentally poisonous for the laborers. In an age without safety occupational policies, most of the laborers (Indians or African slaves) were dying because of the nature of the fermenting and beating process to extract the tincture in blocks or powder. It not only involved environmental concerns to the rivers and air around the obrajes, but it also caused cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, skin irritation, genotoxicity, carcinogenic effects, and death. This is why the Indians ran away from blue-dye manufacturing, and African slaves took their place. When the prohibition was annulled by Charles III Bourbon Farnese Wittelsbach, things turned sour for the native peoples. Researchers have discovered a positive correlation between forced slavery and the Indigo trade in the kingdom of Guatemala. Additionally, the shortage of labor for Indigo crops and their respective production caused the importation of African slaves, through legal or illegal proceedings. An interesting fact is that one of the departments of El Salvador, San Vicente, was the hub for the society of Cosecheros de Añil of the Guatemala kingdom. The Marqués de Aycinena held several properties there at that time. Read slide 11.

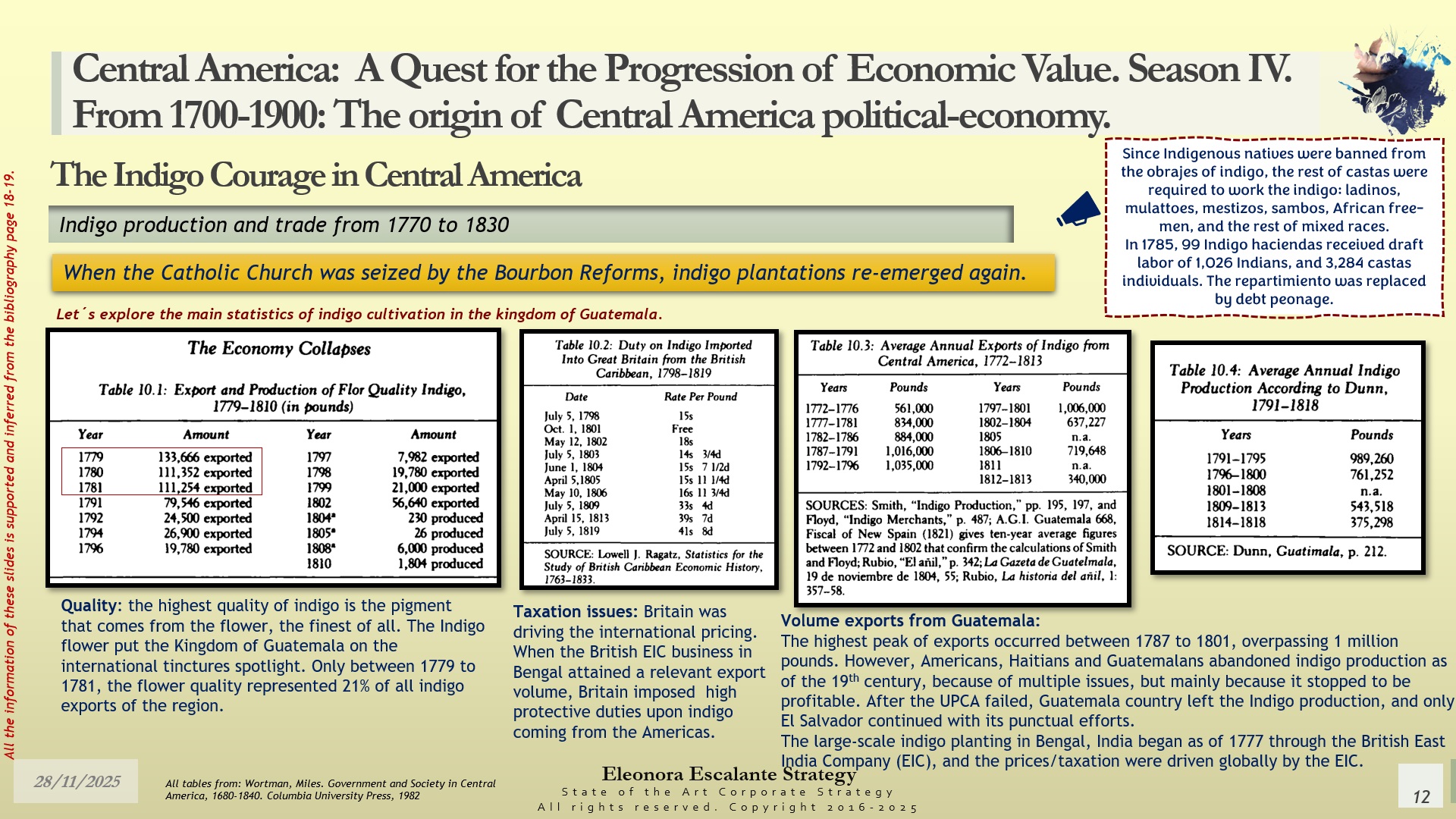

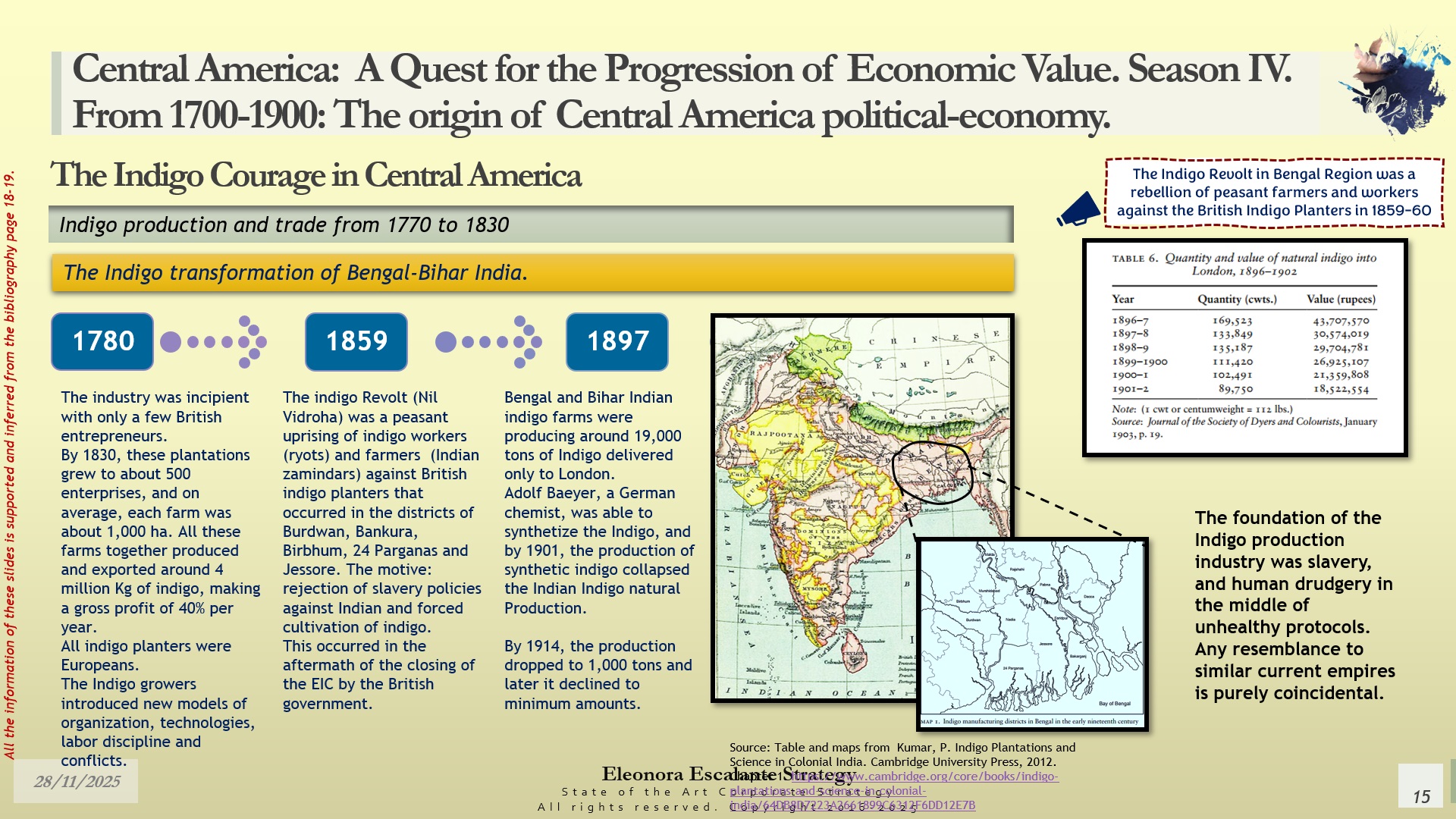

4. Indigo Production and Trade from 1770 to 1830. Slides 12-17.

All these slides are self-explanatory. We tried to provide analysis and reflections in each of them. Slides 12 and 13 are about data. Data collected by historians and filtered with the most relevant numbers available. Even if there is a percentage of error on it, we strongly believe that all these tables show reality as it was; we suggest that Miles Wortman’s numbers (4) should be augmented by 33%. Around 1/3 of the production of indigo was going directly to smugglers and multiple corruption chains that involved the bureaucratic officials and the intermediaries. The years with the highest exports of indigo were between 1779 to 1781, with high-quality flower; the rest of indigo was mainly exported between 1787 to 1801, at a rate of one million pounds per year. Then, Britain provoked the shift of the Indigo planting/manufacturing scenario to Bengal, India, for several reasons that we discuss on slides 14 and 15. Please re-read these slides. These are core slides for you. Britain required an ensured flow of Indigo for its textiles production, and the Empire of the British monarchs, George III, George IV, and Queen Victoria of Hannover-Saxe Coburg-Gotha contributed to its planting and manufacturing expansion as of 1777. It wasn´t until 1794 that indigo exports from Bengal overpassed the one million pounds of Guatemala, and it continued rising through the 19th century. I would like to remark that the demand was driven by British textiles, boosted by the first industrial revolution and its associated requirements for the pigment in Europe´s clothing. Britain created a backward vertical integration of its textiles value chain in India, and the Indigo Industry of Central America was sunk forever.

In summary (see slides 16 and 17): The globalization of indigo manufacturing was a global economic success for the British Empire, but it was also a tremendous tragedy of accomplishment based on the slavery of human labor. For Eleonora Escalante Strategy, this episode of our civilization commercial ventures goes beyond historical chronicles. It is another wake-up call to acknowledge that all our business models of today are founded on the same old song: cheap labor. There have been drastic improvements in safety occupational measures since then. However, there are still production factors that have not philosophically changed, and are keeping the middle class growth stagnant.

As a final illustration of our current economic disaster, we would like to share a parallel situation to Indigo´s endeavors in the 21st century. The top digital economies began to invest in the NAIQIs by the year 2013. The economic growth in GDP terms has been low since then. The pandemic did not improve the numbers, and the digital economy won´t offer that growth either in the future. Why? Our business models are still answering the premises of an indigo low-cost strategy, replacing middle-class humans with machines and applications. Not all the digital technologies available are creating prosperity for humans, but are reducing the number of jobs required for the economy to function. For every new job created under NAIQI’s requirements, at least 2 to 5 jobs are buried forever. Just add and subtract, please. It is the nature of this disruption that is damaging the recipe. All the past Industrial Revolutions did not consider the well-being of humans, but rather the low-cost manufacturing. And here we are. Year 2025, and we are facing the reason why the top digital economies are not prospering the world anymore. See the next two slides (BONUS).

To be continued…

Closing words. Announcement.

This chapter is the perfect example of how entrepreneurial economies producing for self-sufficiency were challenged by global mercantilism and the first industrial revolution of the British/Northern Germany Empire. The globalization of indigo was based on cheap labor and slavery, where the occupational safety issues of its production contributed to its ethical economic failure. No industry is triumphant or successful if it is based on inhuman slavery, on unhealthy, toxic operational procedures for its workers, or if it doesn´t help to expand the middle class of all its stakeholders.

Our next chapter is Episode 12. The cacao industry of Central America. Thank you.

Musical Section.

During season IV of “Central America: A Quest for the Progression of Economic Value,” we will continue displaying prominent virtuosos who play the guitar beautifully. However, we will select younger interpreters who promise to become the new cohort of classical guitarists in the present and future. It is a hard task to include all the guitarists that have reached the top plateau, but trust us, we are trying to embrace them all here.

Today, we have selected Andjela Misic from Serbia. She shared this beautiful piece just 12 days ago on her YouTube channel. She is interpreting Intro&Alma composed by Antonio Rey at Suma Flamenca Joven Festival 2025. Her profile is here: https://www.siccasguitars.com/blogs/guitarists/andjela-misic?. Enjoy!

Thank you for reading http://www.eleonoraescalantestrategy.com. It is a privilege to learn. Blessings.

Sources of reference and Bibliography utilized today. All are listed in the slide document. Additional material will be added when we upload the strategic reflections.

(1) Tracy, J. The rise of Merchant Empires. Chapter 3 – Niels Steengaard. The growth and compostion of the long-distance trade of England and the Dutch republic before 1750. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/rise-of-merchant-empires/0057F3ECBE7A50F6A4301FCC5377C046

(2) Melville, E. Land Use and the transformation of the Environment. Chapter 4 in Volume I of “the Cambridge economic history of Latin America”. Edited by Bulmer-Thomas, Coatsworth and Cortes Conde. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-economic-history-of-latin-america/11F6DFB24F8AFAC941D70A494D371392

(3) Erquicia, H. Obrajes para beneficiar añil en San Vicente y La Paz Reconocimiento y registro de sitios arquológicos históricos de El Salvador. La Universidad. July 2013-March 2014.https://www.academia.edu/64080542/Obrajes_para_beneficiar_a%C3%B1il_en_San_Vicente_y_La_Paz_Reconocimiento_y_registro_de_sitios_arqueol%C3%B3gicos_hist%C3%B3ricos_de_El_Salvador

(4) Wortman, Miles. Government and Society in Central America, 1680-1840. Columbia University Press, 1982. Chapter 10. The economy collapses. https://www.abebooks.com/Government-Society-Central-America-1680-1840-Miles/32155494029/bd

Disclaimer: Eleonora Escalante paints Illustrations in Watercolor. Other types of illustrations or videos (which are not mine) are used for educational purposes ONLY. All are used as Illustrative and non-commercial images. Utilized only informatively for the public good. Nevertheless, most of this blog’s pictures, images, and videos are not mine. Unless otherwise stated, I do not own any lovely photos or images.